The story of Temple Tifereth Israel is partly architectural. That means, to begin with, the story of its remarkable building. But that story is also part of a larger one, including the growth of the Sephardic congregation, a parallel growth and westward movement of Los Angeles, and the growth and relocation of Jewish communities across the country in the years after the second World War, a process that included the construction of new synagogues from coast to coast.

The challenge of creating architectural settings for “modern” American Jews had been the subject of lively discussion in the national Jewish press in the years after World War II. Commentary, the magazine founded by the National Jewish Committee in 1945, raised the question of what one writer (the art historian Rachel Wischnitzer) called “The problem of Synagogue Architecture: Creating a style expressive of America.” The problem, as that title hints, is balancing tradition and contemporary taste, expressing both Jewish and American identity—a balance that will meet the standards of architects and temple building committees. She urged congregations to seek “something new, expressive of a more self-conscious Jewishness, at home in America.” 1

Commentary soon became the forum for discussing issues of synagogue design, which often turned out to be issues of identity. Should new synagogues adopt styles evoking the past (as had been the practice in such buildings as the Wilshire Blvd Synagogue of 1929) or try to develop a more authentic modern American idiom? In essays by prominent architects and art historians, that second view was strongly in the majority, voiced perhaps most strongly by Erich Mendelsohn, the modernist German-Jewish architect who had fled the Nazis and moved to England in 1933 and then to the United States in 1941. His views are made clear in the title of his essay of 1947, “In the Spirit of Our Age.” His goal is both a contemporary architectural aesthetic and a contemporary Jewish identity, design that positions Jews as “full participants in this momentous period of American history.”2

The period was marked by movement from cities to suburbs, where many new synagogues (most often associated with the Reform movement) were built in a variety of contemporary styles. The most influential figure behind this expansion (the Forward called him “America’s Most Prolific Synagogue Architect” in a 2001 retrospective) was Percival Goodman (brother and sometime collaborator of the famous social philosopher Paul Goodman), who from 1936 to 1979 designed more than fifty synagogues around the United States.They were, as the critic Paul Goldberger put it, “assertive, modernist structures, reflecting Mr. Goodman’s belief that the vocabulary of modern architecture could be transformed into something rich enough to express powerful religious feeling.” His goal was “to design synagogues that interpreted Jewish tradition in modern ways.”3

The challenge facing Temple Tifereth Israel was more basic than this: the need to expand and move closer to the homes of many of its congregants. It was not an easy goal to reach. The synagogue had purchased land far to the west of its original central Los Angeles location, and Westwood residents were not entirely enthusiastic about the prospect of a new institutional presence (the word “Jewish” was never mentioned) on its central Wilshire Blvd thoroughfare. The street had included other religious buildings, in traditional styles, for decades. The Westwood United Methodist Church, across the intersection from Tifereth Israel, had been completed in its present neo-gothic form in 1949.

Many apartments also had been constructed in traditional styles, such as Chateau Colline (10337 Wilshire), built in 1935. But Tifereth Israel somehow seemed to add the wrong element to the street. The synagogue’s first request for a building permit was denied in September 1967, partly in response to neighborhood opposition. The Zoning Authority stated that the synagogue would be “entirely incompatible and out of harmony with the quality of single-family residential development southeasterly of Aston Avenue and the low density multiple residential development along the northwesterly.”4

Temple Tifereth Israel appealed the Zoning Authority ruling to the City Council in December, 1967, where the synagogue’s attorney argued (according to the LA Times) that the proposed building would be “much less objectionable” than the sorts of high-rise apartments that then-current R-5 zoning allowed.5 The City Council finally voted 12-1 the following January to approve the project. Ground breaking took place in 1970. Now, 50 years later and with the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that by allowing the synagogue to enter the so-called “buffer strip” between single-family homes and high-rise apartments, the City created an even more effective buffer between those high-rises themselves.

Wilshire had not always been dotted with tall buildings. The first of the high-rise apartments was completed in 1951 (at the corner of Beverly Glen). By the 1970s, a half-dozen more were added. By today’s standards, the street retained a modestly low profile. But it was already an important address, one (as the architect recalls) that was particularly important to the synagogue community. The street did not yet have the glamor of what came to be known as the Golden Mile, but Wilshire was changing. If Westwood residents in 1967 saw Tifereth Israel as out of keeping with the low-rise, residential character of the neighborhood, by the time of its official dedication in 1981, when the Wilshire Corridor had begun to form, it could have been seen as a visual anchor of a more traditional community.

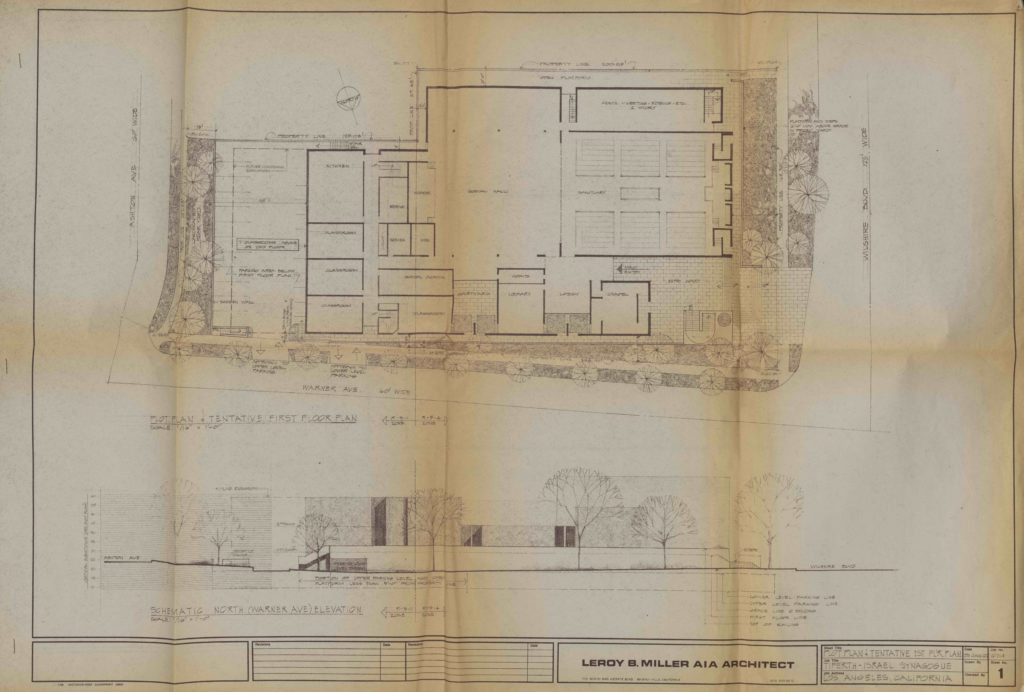

None of this, however, speaks to the unique character of the building itself. For that, the congregation can thank an unusual architect and a remarkable stroke of luck. And as sometimes happens, good luck began as its opposite—with a set of plans that at least one member of the synagogue community found disappointing. Uneasy about the proposed design, Ike Caraco, then a Vice President of the Bechtel Corporation, enlisted the help of Nubar Shahbazian, an architect working in a small architectural division of Bechtel. As Shahbazian retold this story in a letter, he was asked “to do some conceptual studies to define what character the building should have.” And, he added, “it went much further than conceptual studies.”6

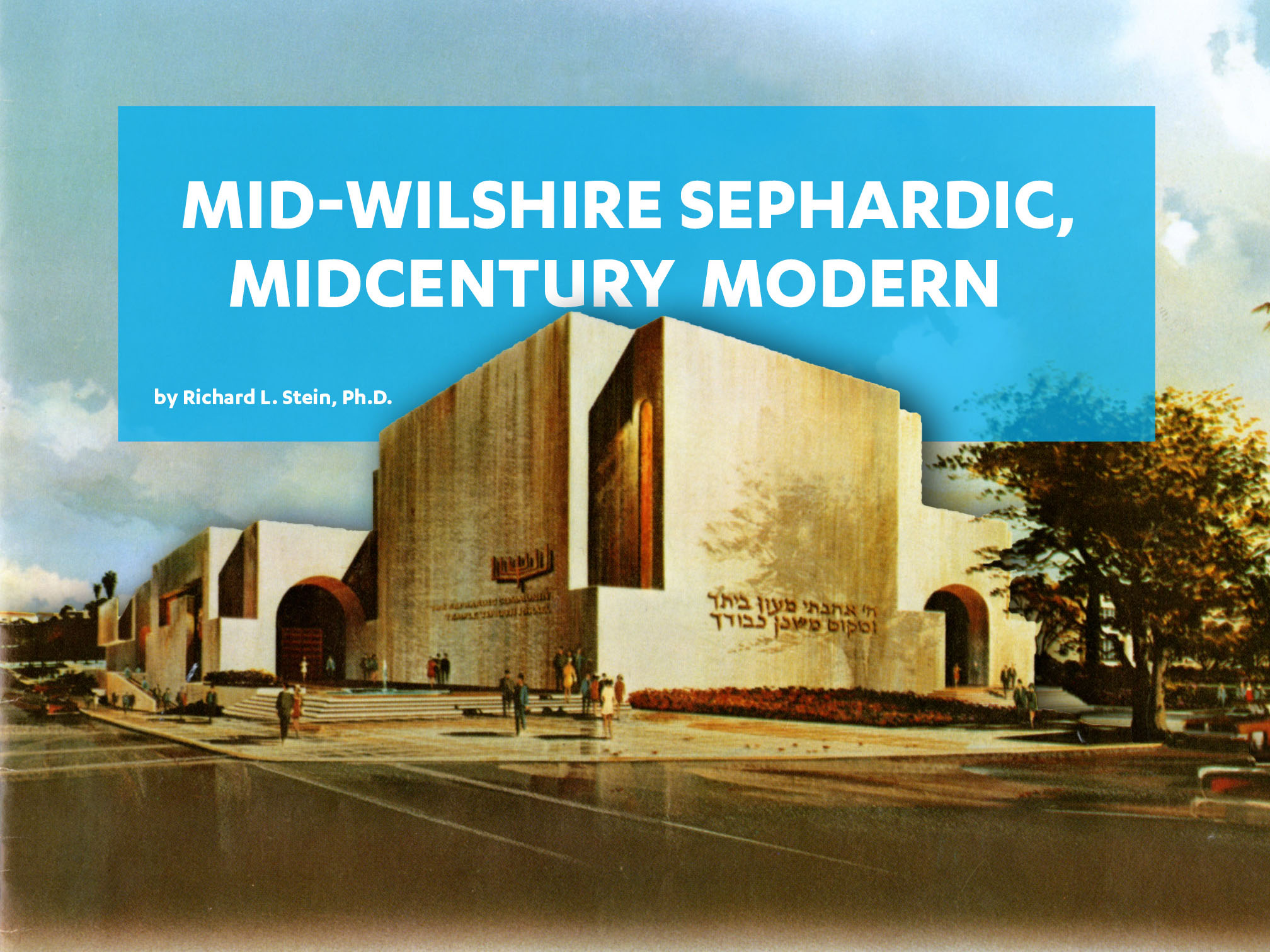

Bechtel could not take on work of this kind, so another firm was needed to oversee the project. The congregation chose a new firm, Brent, Goldman, Robbins, & Brown, organized by old friends and colleagues of Shahbazian, who then was officially listed as the building’s “design consultant.” But Shahbazian continued to develop his ideas in collaboration with the building committee. This meant, as he explained, “long meetings, discussions, and visits to other Temples. I took the thing through full Schematic Design. I had a rendering made… and drew floor plans, sections, etc. The rendering was shown to the full congregation and they loved it.” In another conversation about that meeting, he explained it a bit differently. “I showed my design to the audience and one member spoke up loudly: ‘The Wall!’ That may have sealed the deal.”7

Shahbazian was referring to Tifereth Israel’s Wilshire façade, which many find reminiscent of the Western Wall. The synagogue website summarizes its design history in these terms: “Plans for the architecture were carefully considered, and finally it was agreed that the temple should be made of stones, to look like the stones of Jerusalem. It was to be built in the style of the Old City of Jerusalem.” The cover of the original fundraising brochure for the project uses the heading “A Temple in the Sephardic Tradition.” The website of the Los Angeles Conservancy similarly notes that the “temple is built of stones, designed to evoke the style of the Old City of Jerusalem, with its massive lines and monumental arches.” It also identifies the architectural style as “monumental.” In 1971, the design was given an Honor Award from the Guild of Religious Architecture, affiliated with the American Institute of Architecture, which described Mr. Shahbazian’s concept as “modern in plan…but designed with the feeling of the architecture of ancient lands.”8

Shahbazian’s own account is different in some interesting respects. To begin with, he had to face a challenge not acknowledged in any accounts of the building or its history: he is not Jewish. To prepare a project of this kind, of this importance, he felt it incumbent on him to study synagogue design and Jewish tradition more broadly. The result was a design with two primary influences. The first he described simply as a “general middle-eastern ambiance,” which is to say including but not limited to Jerusalem. Shahbazian also drew inspiration from the recent work of the most important 20th-century American Jewish architect, Louis Kahn, who at the time was developing plans for two innovative synagogues (in Philadelphia and Jerusalem). While neither project was ultimately completed, at least one of those designs could have come to Shahbazian’s attention in his research. The cover of one of the most influential books on synagogue architecture then available—the catalogue (edited by Richard Meier, who later designed the Getty Center among many other works) of an exhibit on “Recent American Synagogue Architecture” at the Jewish Museum—featured a Kahn drawing for the Sephardic Temple Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, a space that strongly anticipates the design for the sanctuary of Tifereth Israel. In Shahbazian’s design, the spacious sanctuary, with seating on the sides flanking a central bimah (a location traditional in Sephardic synagogues), is the defining interior feature.

The facing galleries of pews, an elegant expression of Tifereth Israel’s congregational decision years before (breaking with Orthodox practice) to allow men and women to sit together, had been required in instructions to the architect from the building committee. The ark, as in Mikveh Israel, is located at the east end of the sanctuary, along with seats for congregational officers. The result is a feeling of both intimacy and volume, created in part by the high ceiling and clerestory lighting that also may reflect Kahn’s example. But his influence is most apparent in the synagogue’s signature space, the simple, geometric arrangement of high stone blocks, plaza, and arches that make up the building’s entrance façade on Wilshire.

The original design (as the first fundraising brochure shows) proposed walls even higher, faced in light gray flamed granite; concrete was substituted, and walls lowered, for reasons of cost. Nevertheless, the cumulative effect of the original design remains: monumentality on a human scale. The solemn visual character of the building is defined in the streetscape, while a more personal experience is created for congregants moving past the largely undecorated walls to the smaller but still formal arched doorways. Monumentality frames a pathway: the façade manages to be imposing and inviting at the same time, a “generous entrance” in Shahbazian’s words.

For all the debts of Temple Tifereth Israel to Kahn, he remains more an inspiration than a model: perhaps most clearly influencing the exterior emphasis on monumental stone and the soaring façade. The synagogue exhibits some of the “quiet stateliness” that Susan G. Solomon (author of Louis I. Kahn’s Jewish Architecture) finds in Kahn’s unrealized design for Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia. It also fits a concise description the great architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable used to sum up Kahn’s work over his lifetime: “strong and subtle.” And even if it does not rise to the level of the master’s classic buildings, Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel remains a distinctive accomplishment with its own dignified character. Part of that dignity is its simplicity, a traditional monumentality that invites us to enter rather than to gaze, not overwhelming visitors with massive or elaborate features.

This stands in sharp contrast to the other major synagogue design on this part of Wilshire—another midcentury building indebted to a major contemporary architect—Sidney Eisenstadt’s 1956 Sinai Temple. “Eisenstadt was a student of Frank Lloyd Wright,” as Robert Winter and David Gebhard explain in their definitive architectural guide to Los Angeles, “This is clear when you look at the entrance to this building, but Eisenstadt makes his own statement.”9 That last word suggests the difference between the two structures. Sinai announces itself as Architecture. Tifereth Israel is marked by understatement. We are less aware of its engineering than its elegance, based on simple, classic geometry. To put it another way, this is modest architecture, hinting at a life within rather than broadcasting its achievement.

What is the source of that distinction? Perhaps in the difference between Orthodox and Conservative congregations, perhaps in that between Sephardic and Ashkenazic traditions. The congregation of Tifereth Israel was made up of Sephardic families originally from Turkey, Rhodes, Greece, Iraq, Egypt, and other areas of the Mizrahi East. Did they prefer a more secluded, less ostentatious space for worship? Did their architect, himself the descendant of immigrants from an adjacent part of the world (his father was a refugee from the Armenian genocide), share that sense of privacy? “I became convinced,” Shahbazian wrote recently, “that the building should be inward looking, secure… perhaps something like a fortress.”10 Did the inwardness of the building develop partly through the shift from central to west Los Angeles, an anticipatory response to a sense of class expectations and snobbery that might meet these new arrivals in a high-rent district? Or was it, in the end, simply an architectural choice—turning away from the stylish European modernism that marked synagogue design in the 1950s in favor of a simpler, more traditional form? These questions are speculative, psychological, and sociological, and probably cannot be answered. But raising them reminds us (as if any reminder is needed) that Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel sets itself apart in its form as well as its content, in an architectural style that seems fully suited to its character as a congregation and to its place within the Sephardic tradition.

Citation MLA: Stein, Richard L. “Mid-Wilshire Sephardic, Midcentury Modern.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/mid-wilshire-sephardic/.

Citation Chicago: Stein, Richard L. “Mid-Wilshire Sephardic, Midcentury Modern.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/mid-wilshire-sephardic/.

About the Author:

Richard L. Stein is a Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Oregon… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Commentary, March 1947.

2 Commentary, June 1947.

3 Goldberger, “Percival Goodman, Obituary,” New York Times, Oct. 12, 1989.

4 Los Angeles Times, Dec. 17, 1967.

5 Ibid.

6 Letter to the author, June 23, 2018.

7 Interview with the author, Sept. 16, 2018.

8 Quoted from STTI fundraising brochure, A Temple in the Sephardic Tradition, Preface, p. 3. STTI Archives, UCLA Library Special Collections.

9 David Gebhard and Robert Winter, An Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles, ed. Robert Winter (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith Publisher, 2003), 143.

10 Letter to the author, June 23, 2018.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.