In the early twentieth century, a Sephardic commercial orbit connected Aleppo, Syria, Paris, New York City, Mexico City, Tijuana, and Los Angeles. Some Sephardic Jewish entrepreneurs successfully leveraged the interdependence of regional economies between Northern Mexico and Southern California, a commercial corridor produced by the redrawing of national borders half a century prior. Drawing on Camila Pastor’s concept of the “Mexican Mahjar,”1 this essay examines the life of Jack Swed, a founding father of Tijuana’s Jewish community, a Sephardic (and Jewish) history shaped by the shifting landscapes of industry, commerce, and tourism in the transborder region.

Jack Marcus Swed was born in Aleppo, Syria on August 19, 1901, or by some accounts 1902, or even 1900. Swed’s hazy date of birth may be a symptom of the rapidly changing times across the Mashriq.2 The economic and political transformation that unfolded across the Middle East and the Mediterranean during the last third of the nineteenth century would continue through the second World War and catalyzed a mass mobilization of migrants in the region then known as the Ottoman Empire. As a young boy, Swed watched as his older family members were absorbed by the industrializing trade markets across Western Europe and the Americas. Swed was still a young boy when his two older brother’s liquidated the remaining assets of their father’s European import business and moved to New York City to join the ranks of immigrants dedicated to international trade. His childhood in Aleppo was marked by his training at a French school. Sources do not clarify the institution, but it was possible that Swed, like many Jews across the Ottoman region, attended the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a Franco-Jewish philanthropic organization that provided secular education to hundreds of Jewish youths across the Mediterranean and Middle East.3

In the fall of 1912, Swed and his mother left their home in Aleppo and joined the remaining members of their nuclear family in New York City. Perhaps given the family’s new cultural and national context, the young Swed was encouraged to break with the long entrepreneurial line and was sent to France in his late teens to study medicine at the L’ecole de Medicine de Roschild. Living alongside his cousins who operated a successful import-export business, Swed nevertheless absorbed the family interest in trade. In 1917, two years into his medical training, he dropped out and moved to Revolutionary-era Mexico to pursue commercial and entrepreneurial endeavors. Between the years 1917 and 1927, Swed worked as a traveling salesperson, or peddler, across the northern Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Coahuila. Mexico may seem like an unlikely site of settlement for an unmarried, aspiring entrepreneur, whose immediate familial and commercial networks were located between New York City, Paris, and Aleppo. However, as historians of the modern Middle Eastern diaspora in Mexico have argued, Revolutionary (1910-1920) and post-Revolutionary Mexico, especially the northern border region, created economic opportunities for muhajirin to become critical providers and sources of credit to the nation.4

Like other Middle Eastern immigrants with extensive transnational ethnic networks, Swed capitalized on new market opportunities, selling dry goods to federal soldiers and rebels factions during the period of active Revolution. In the wake of civil war, Swed catered to a population of Mexican nationals working in the booming oil industry of Tampico, Tamaulipas, selling imported French lingerie and watches. Swed’s connections to a broader immigrant trade network, his loose affiliations with a nation or national cause, and his linguistic proficiency across multiple languages, including Spanish, English, Arabic, French, German, Hebrew, and Yiddish, marked him as uniquely situated for entrepreneurship and an atypical reflection of the Middle Eastern immigrant experience in Northern Mexico during the early decades of the twentieth century.

Mexico City severed as a consistent second home for Swed during his first decade in Mexico. Mirroring the patterns of commercial mobility enacted by Sephardic immigrants to Mexico during the colonial period, Swed traveled back and forth to the nation’s capital to connect with other Sephardic immigrants and acquire dry goods and clothing for resale in the rural northern territories near mining towns and oil rich cities.5 His trip in Mexico City 1927, however, shifted this routine trade circuit. Browsing through a newspaper from the lobby of the Hotel Interbide, Swed read that Tijuana, the small, rural border town across from San Diego, California, was undergoing an unprecedented period of commercial and urban expansion. The economic development of the city was largely a response to the market for alcoholic that legally, due to Prohibition and the Volstead Act (1919), necessitated a shift outside the national boundaries of the U.S.

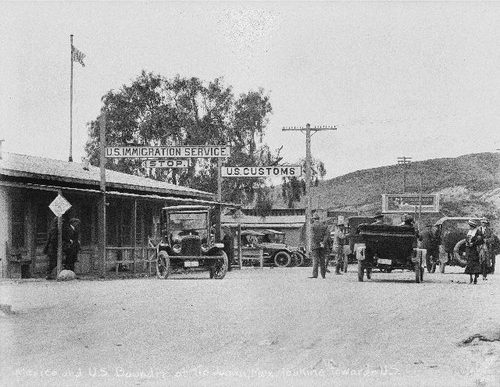

Swed took this as an invitation for his next commercial endeavor and began the circuitous train route north from Mexico City, through the transborder desert region that connected the states of Sonora and Arizona. At this time, to access Baja California by rail from Mexico required crossing into the U. S. and then back into Mexican territory.6 According to Swed’s own testimony, he did not have a visa nor any required government documentation to ensure this cross-border journey. Rather, Swed recalls that he was allowed to cross into back into Mexico because the immigration authorities at the port-of-entry between San Diego and Tijuana were old friends from Tampico, Tamaulipas.7

Swed’s fluid, cross-border mobility is remarkable not only in contrast to our contemporary moment, but also within the context of U.S.-Mexico border surveillance in the 1920s. The passage of new national immigration quotas and establishment of the U.S. Border Patrol as a new agency to enforce them between 1921 and 1924, alongside the establishment of the Mexican Department of Migration in 1926, suggest that the 1920s were a crucial turning point in solidifying migration control and border enforcement as a binational project between the U.S. and Mexico.7 Swed’s anecdotes of border crossings during this time of renewed binational migrant surveillance provide an example of how a Sephardic migrant with French citizenship (by way of Syria’s French mandate) could operate outside the legal boundaries of cross-border mobility as established by the US and Mexico in the early decades of the twentieth century.

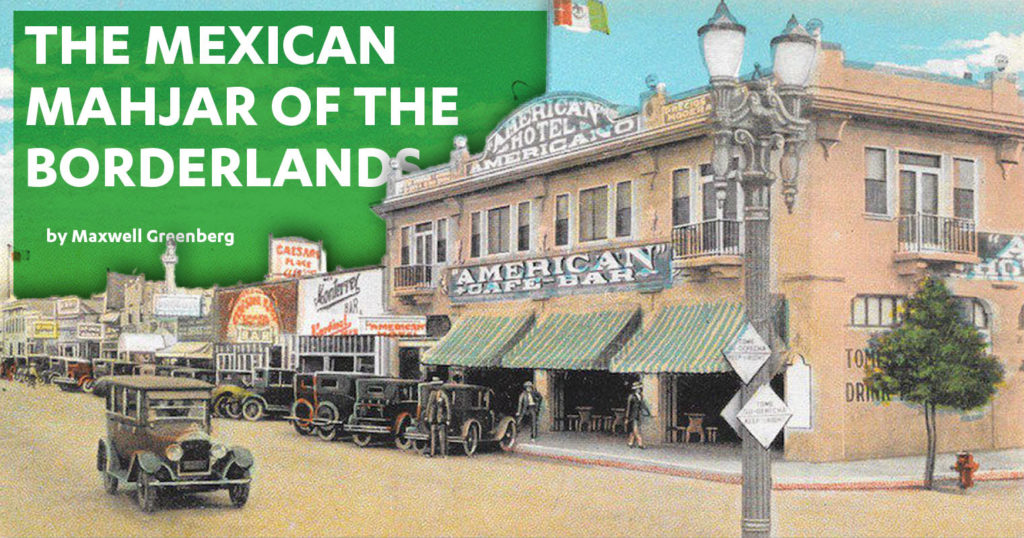

Upon his arrival to Tijuana, a permanent space for Swed’s import-export business in Tijuana’s bustling tourist district along Avenida Revolución proved a high cost endeavor. However, upon identifying a fellow Jewish entrepreneur who owned commercial property downtown, Swed negotiated a highly subsidized agreement for the rental of a storefront. After a decade of working as a traveling merchant across large swaths of Mexico’s northern territory, Swed opened the doors to his first permanent store: Swed’s Imports, located on Avenida Revolución between 1st and 2nd Streets. A trusted proprietor of French perfume and cashmere, women’s clothing, English jackets, and Rolex watches, Swed’s business benefited from the enduring market demands catalyzed by U.S. prohibition, his expansive trade networks between Mexico, the U.S., and Western Europe, and the declaration of Baja California as a duty free zone in 1932.9

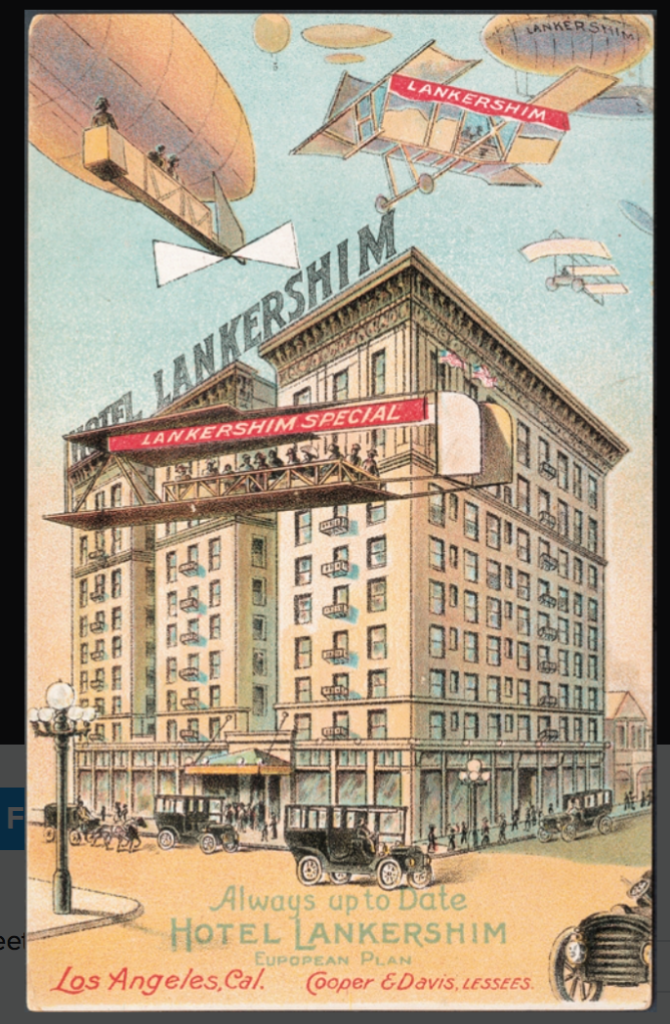

National Archival records of Swed’s border crossing activities between Baja California and California suggest that Los Angeles had replaced Mexico City as a crucial site in his commercial orbit. Manifests of Swed’s border crossing card, a form of non-immigrant visa, which allows border region residents to make personal and business trips across the border for up to 72 hours, mark Swed’s California residence at the Lankershim Hotel on 7th and Broadway in downtown Los Angeles. During the interwar period, this area of downtown was peppered with department stores and theaters, suggesting that Swed’s temporary residencies in Los Angeles were business oriented and aimed at acquiring the latest fashions for resale back in Tijuana.

Swed’s business travels also followed the contours of a growing tourism corridor between Los Angeles-San Diego and Tijuana-Ensenada that remained active well into the interwar period. Angelenos, particularly the Hollywood glitterati and business elites, as well as enlisted members of the US military, frequently crossed the border to enjoy luxuries, both elicit and conventional, from wide array of bars, restaurants, casinos, and spas that Tijuana offered. Swed proudly recounts in his own autobiography that his import store, which eventually grew to a staff of 15, was visited by Angeleno entertainment darlings from the likes of Rudy Valle, Tom Mix, Carole Lombard to the sisters Joan and Constance Bennett, and Al Jolson.10

Swed’s settlement in Tijuana, while initially for commercial reasons, is also central to the modern Jewish history of the border city. In the years after World War II, Jack Swed and his wife Shirley would host the first high holidays service in Tijuana’s history, inviting a near 100 people from across Baja California and even western Sonora into their home for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services. This initial informal gathering of Jews in the border region evolved into the first modern synagogue in the city, the Magen David. The life and legacy of Jack Swed serves as an enduring reminder that L.A’s Sephardic history does not conform to national boundaries but rather, reflects how some Sephardic immigrants to North America operated within a commercial network of nationally, culturally, and linguistically fluid and ambiguous borders.

Citation MLA: Greenberg, Maxwell. “The Mexican Mahjar of the Borderlands.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by in ed. Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/the-mexican-mahjar/.

Citation Chicago: Greenberg, Maxwell. “The Mexican Mahjar of the Borderlands.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/the-mexican-mahjar/.

About the Author:

Maxwell Greenberg is a PhD candidate in the César E. Chávez Department of Chicana/o Studies at UCLA… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Pastor expands “mahjar,” a term used by Arabic speakers to describe geographies and sociabilities inhabited by migrants of the Arabic-speaking countries of the Eastern Mediterranean since the nineteenth century, to delimit the borderlands of the southwest as a space of migration, diasporic homeland, and dwelling in movement. See Camila Pastor, The Mexican Mahjar: Transnational Maronites, Jews and Arabs under the French Mandate (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017).

2 Mashriq refers to Arabic-speaking countries of the Eastern Mediterranean. See Pastor, The Mexican Mahjar, 2.

3 Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey through the Twentieth Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), 22.

4 Pastor, The Mexican Mahjar, 2. See also Teresa Alfaro-Velcamp, So Far from Allah, So Close to Mexico: Middle Eastern Immigrants in Modern Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 74-79.

5 Stanley Hordes, To the End of the Earth: A History of the Crypto-Jews of New Mexico (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

6 Baja California would remain disconnected from the rest of Mexico until post-War. The construction of the Sonora-Baja California railroad began in 1948. See David Piñera and Gabriel Rivera, Tijuana in History: Just Crossing the Border (Tijuana: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 2013), 197.

7 Donald Harrison, “Yiddishkeit in Tijuana,” San Diego Jewish Press Heritage, February 25, 1993.

8 The national origins quotas were initially passed as temporary, emergency provisions in the Immigration Act of 1921 and made permanent in the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924. While neither explicitly targeted Jews as an ethnic or religious group, they did severely limit entries from countries across Eastern and Southern Europe from which the majority of Jewish immigrants came to the United States, including Syria where the maximum number of entries was reduced to 100 individuals per year. For more, see Kelly Lytle-Hernandez, Migra!: A History of the US Border Patrol (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

9 Piñera and Rivera, Tijuana in History, 171.

10 Harrison, “Yiddishkeit in Tijuana.”

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.