In late autumn of 2015, one of the research fellows at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) rushed me from a big event—a gathering of donors to the museum, many of them first-, second-, and third-generation descendants of Holocaust survivors—to introduce me to Harry Zinn. The name sounded neither familiar nor unfamiliar; Zinn can be German, Austrian, Czech, Slovak, and of course (but not necessarily) Jewish, and Harry—I don’t know precisely why—always reminded me of Hollywood movies. So on the one hand, it came as no surprise when I learned that Harry Zinn arrived in D.C. from Los Angeles. On the other hand, I was struck by his reasons for wanting to meet me: not only was he interested because of my Czechoslovakian origin but also because of my research on the Jews of Greece. I soon learned that these interests reflected his own identity: his father was a Jew from prewar Czechoslovakia who married a Jewish woman from Greece in the wake of the Holocaust. He invited me to visit him in Los Angeles, where I interviewed him and his aunt, Laura, about their family history.

In the years after World War II, Jewish survivors of the Holocaust struggled to rebuild their lives out of unfathomable tragedy and loss. After 1948—with the establishment of the State of Israel and the United States Congress’ passage of the Displaced Persons Act—hundreds and thousands of survivors emigrated out of Europe, a period of massive global resettlement during which some 15,000 survivors came to Los Angeles. This period of Jewish immigration was distinct from previous waves of migration in several respects and resulted in many Jewish families, in the USA and elsewhere, severing all their personal ties to Europe. But it also fostered unprecedented interaction and intermingling between young Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews. Brought together by overlapping experiences, both during and after the war, once unlikely meet-ups–given the geography of Europe, linguistic and cultural barriers, and the diversity of European Jewish traditions–grew into martial bonds. This was the case for Sarah Haim and Eugene Czinn, the parents of Harry Zinn. The postwar political situation in their countries of origin, the difficulty of reconstruction of postwar life in general and Jewish life in particular, and their traumatic memories took them away from the places they used to call “home” and united them in marriage in Los Angeles in 1959.

Sarah Haim and World War II in Greece

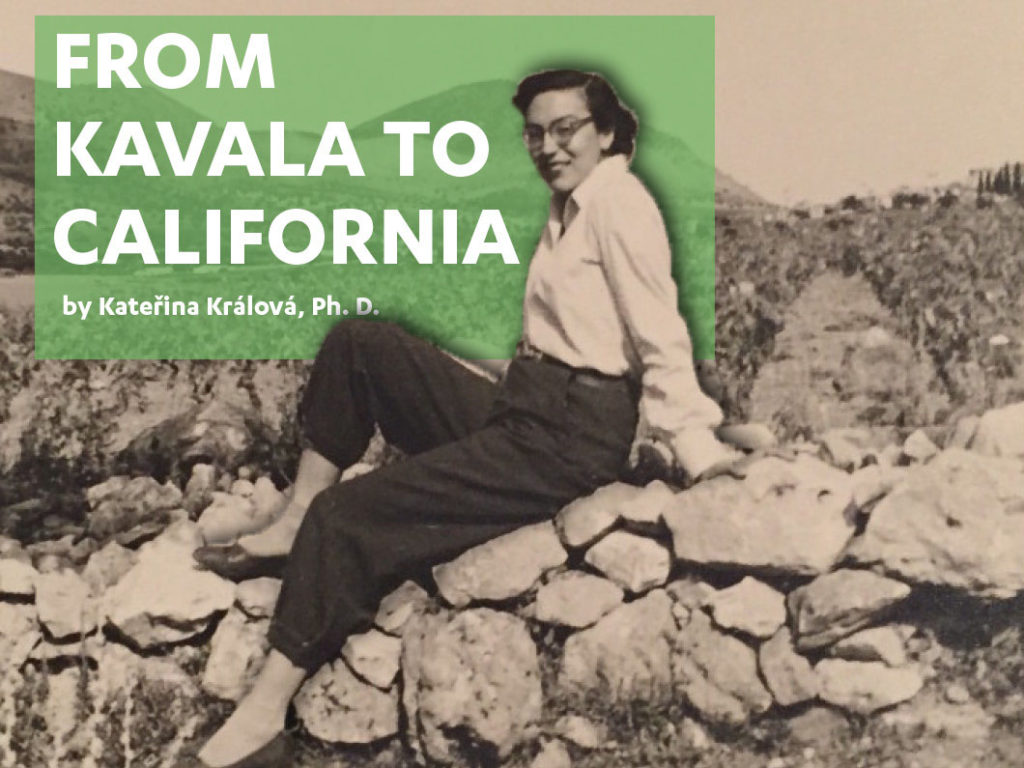

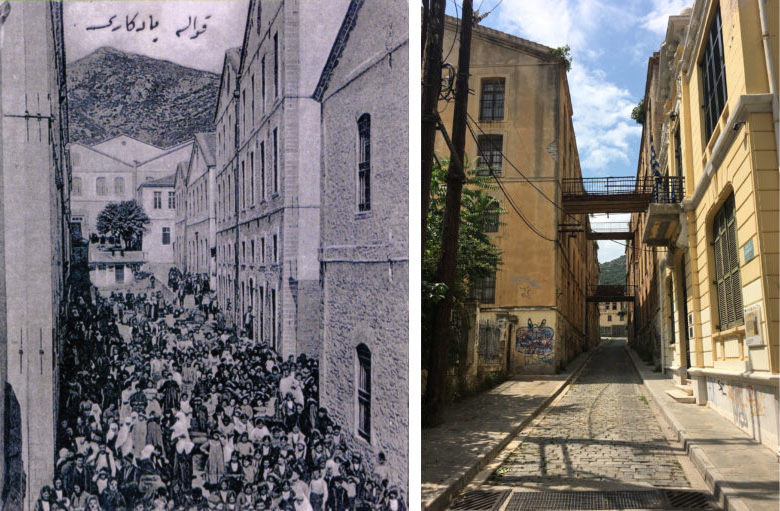

Sarah Haim was born to a Sephardic family in 1928 in Kavala, a beautiful port town on the northern edge of the Aegean Sea, where her father, Eliezer Haim, ran a thriving family business called Solomon Brothers & Co. In the fall of 1940, when the Italian army invaded Greece from Albania, Eliezer packed his wife Henrietta (originally from Salonika), his three daughters, and a Jewish maid and moved them to the apparent relative safety of Athens. He could not yet know how prescient his decision was, nor that his comfortable middle-class life, business assets, and family summers on the picturesque island of Thasos would be lost forever. Soon both the German army and the Bulgarian army invaded as well and nearly the entire northern region of Greece, including Kavala, was engulfed in violent conflict. Athens, by contrast, remained in the Italian-occupied zone with a much more moderate policy toward Jews until the surrender of Rome in September 1943.1

Though Eliezer and family followed Sephardic transitions, he was a modern entrepreneur, liberal in his Jewish feelings and not particularly religiously observant. Unlike many other Sephardic Jews in Greece of his age and strata, he spoke not only Judeo-Spanish and French but also Greek and Italian. Thanks to his business and his Greek Orthodox business associates, he had good non-Jewish connections in the Greek capital, which were instrumental in finding necessary aid and shelter.

When the Germans took over the Italian zone (including Athens) and employed severe anti-Jewish measures in late 1943, the Haim family took on false identities and went into hiding. However, Allegra (b. 1925), Eliezer’s eldest daughter aged eighteen, was soon captured and deported to Auschwitz in 1944. She never returned. Despite having enough financial means to survive in times of famine—an unprecedented disaster that caused the deaths of 250,000 people in Greece between 1941 and 1943—Eliezer became ill, probably with tuberculosis.2 Given the persecution of Jews and ongoing deportations, the family was unable to get him proper health care and he eventually passed away in September 1944 near the very end of the German occupation of Greece. After the deportation to Auschwitz of one of the family members, being blackmailed and betrayed, robbed of the last of their valuables, and finally losing their breadwinner, the emaciated mother and her two half-starving daughters lived out the rest of the war under deplorable conditions.3

And then the Germans weren’t there anymore and then it was quiet, everything was so quiet. Couldn’t understand what was going on… nobody on the street. Nothing, nothing, so Sarah and I, oh oh, we were so hungry, so hungry we decided to see what’s going on, we opened the door, mind you, we were living in one room inside of a house like the royal family… Slowly people started coming here from all over. I could not understand where are they coming from? The whole street became like an ocean of people. And we couldn’t understand and the bells started ringing.”4

The next day, both sisters, who could not yet fully internalize that the war was over, walked miles from Piraeus to their pre-hiding flat in the center of Athens, which they found locked but at least abandoned.

While Laura stayed behind in Greece to care for her mother, who was mourning for her deceased daughter and husband as well as for the overall Jewish tragedy, Sarah, a slight, black-haired, bespectacled, and self-confident teenager, decided to leave to help build a new Jewish homeland in Palestine. Her journey stretched, however, over five months. The “Henrietta Szold,” the ship she boarded in Greece at the end of July 1946, was denied entry into Palestinian territory by the British Mandate. Sarah and her other 545 traveling companions were sent to British internment camps in Cyprus, where they spent the rest of 1946 until finally allowed to enter Palestine in Haifa on December 11. At the registration camp in Atlit, she declared an early December 25 birthdate, about two-and-a-half years older than her actual age, to make herself an adult. This enabled her to be assigned to the kibbutz HaGoshrim, in the Upper Galilee, which recently had been founded by Ladino-speaking Jews, primarily from Greece and Turkey. There, Sarah received not only military but also professional training as a teacher and childcare provider.5

In the early 1950s, after the Greek Civil War ended, Sarah, along with her mother Henrietta and sister Laura, decided to move to the United States with the help of HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), an American Jewish organization devoted to aiding refugees. Only there did Henrietta finally take off her black clothes of mourning. Sarah, by then an Israeli citizen, reluctantly returned to Greece in 1953 to join her mother and younger sister for the journey. Embarking in Piraeus with exactly ten pieces of luggage they reached New York at the end of October in 1955. New York was a just a way station; they had already made up their minds to come to California where two married Greek émigré cousins lived and where, the sisters hoped, they could give their mother “a chance to be happy” again. So, a few days after arriving in New York, they boarded a train to Los Angeles, joining the thousands of American Jews and GIs who flocked to the “Golden Cities” of the Sunbelt after World War II.6 From an apartment on Figueroa Street, the daughters commuted daily to the Max Factor cosmetics factory to earn a living. They also attended Los Angeles City College to learn English and complete their educations.

Laura (Haim) Simon describes the family’s move to Los Angeles in an interview with Kateřina Králová (Woodland Hills, CA, January 3, 2016).

When Sarah met Eugene

Perhaps it was her fate that, in 1958, it was in California, not Israel, where Sarah went on a blind date with her husband to be, Eugene Zinn (who had simplified his name from Czinn for ease of English pronunciation). Eugene’s upbringing was quite different than Sarah’s: born in 1924, he was raised in a conservative, German-speaking Ashkenazi family in Czechoslovakia. In March 1942, Eugene was deported to the extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he incredibly endured 33 months, surviving three selections to the gas chambers. He was the only member of his immediately family to survive, as his parents and three siblings all were murdered in the Majdanek concentration camp. All told, over 80 of Eugene’s relatives died in the Holocaust.

While the postwar political turbulence in Greece brought to power a conservative, anti-communist government, postwar Czechoslovakia oscillated towards Moscow, eventually becoming an integral part of the Soviet Eastern Bloc in February 1948. As in many other countries, anti-Jewish sentiments did not disappear with the end of the war and so in 1948, two years after Sarah, Eugene too emigrated to Israel seeking refuge. In those turbulent times, he surreptitiously left the Czech army into which he had been conscripted using the notorious “Greek Card.”7 He recalled:

“It was Thursday morning I got released from the army, Friday morning I had a passport as a Greek refugee, that I am a Greek refugee on the way home through Paris. From–I mean this is the craziest thing–from Czechoslovakia to go to Paris to go home as a Greek refugee.”8

But instead, in June 1948 he boarded the cargo ship “Altalena,” which (without Eugene’s knowledge) was loaded with guns and fighters to strengthen the Jewish paramilitary units of the Irgun.9 This unfortunate entry in his record later obstructed any chance to get a decent job in Israel, from which he finally left for the USA in November 1955.10

After some time in New York, he moved to Florida, where he worked long shifts for $1 an hour as a busboy. Two years later, he moved to join his cousin Ernest, also a Holocaust survivor, in Los Angeles. He studied engineering at L.A. City College and started working for Everest & Jennings, an international wheelchair manufacturer. From a simple draftsman, he was repeatedly promoted, ultimately to manager of engineering. Among other things, in 1987, he invented a mobile footrest unit for wheelchairs making the life of many war veterans somehow more endurable, and designed a line of lightweight wheelchairs which bore the name “EZ” after his initials.

It was Eugene’s cousin Ernest who first introduced him to Sarah Haim. Their shared time in Israel helped Sarah and Eugene to get to know one another: while they had been raised speaking different languages, they both could communicate fluently in Hebrew owing to their years there. Both were also learning English and practiced together as they courted. They married in Los Angeles in July 1959.

Building a New Life in Los Angeles

Two years after their marriage, Sarah and Eugene both became naturalized U.S. Citizens. Sarah’s sister Laura did so as well, but their mother Henrietta remained a Judeo-Spanish and French-speaking citizen of Greece who never gained more than a limited knowledge of English. Sarah and Eugene, living together with their mother (in-law) had two children, Harry and Helene. They settled in a modest three-bedroom home in the West Hills suburb of the San Fernando Valley, parents in one room, children in the other, and Henrietta in the third. It took Sarah many years to adjust to suburban life, learn to drive a car (out of necessity), and finally—once the children were older—to get back to her beloved teaching. Sarah compensated for the relative solitude of the suburbs by lengthy phone calls with her sister Laura in Greek, which no other family member could really understand, and by regular weekend family gatherings.

Despite having only one, rather reclusive, Ashkenazi relative on Eugene’s side of the family, much of the children’s religious upbringing was in the Ashkenazi tradition. Eugene was far more religiously observant than was Sarah; he had been raised in an Orthodox Jewish family in the village of Huncovce in the Tatra Mountains of northern Slovakia. In California, the Zinn family attended services at a nearby conservative synagogue, where Harry was bar mitzvahed. At the Shabbat table, the family lit candles every Friday night and Eugene recited the blessing in Hebrew over the children. But for holidays like Passover, they used both an Ashkenazi Haggadah as well as another one in Hebrew, Greek, and Judeo-Spanish printed in Athens. When Henrietta, called nona (grandmother in Judeo-Spanish) by her four grandchildren, and her generation were alive, speaking and singing in Judeo-Spanish was common, but it did not continue after they passed away, given the limited understanding of the language by the younger generations. For Sarah and Henrietta, Judeo-Spanish was the everyday household language, and Harry, the eldest of the grandchildren, learned it to some degree. But the other grandchildren and Henrietta’s two sons-in-law did not share a common language with her, making verbal communications challenging. And with her sister Laura, Sarah communicated primarily in Greek.

Laura (Haim) Simon discusses language in an interview with Kateřina Králová (Woodland Hills, CA, January 3, 2016).

The Sephardic influence of the women of the Haim family manifested itself above all through food and food-related holiday customs. Although Sarah, a wonderful cook, learned how to make Ashkenazi dishes like chicken soup, beef brisket, potato knishes, and cholent stew for her husband and family, for holidays and special occasions the table was filled with traditional Sephardic dishes. For Passover, Sarah made huevos haminados, slow-cooked hard-boiled eggs baked with onion skins and a bit of instant coffee for color that came out a beautiful creamy light brown. The family charoset was a Mediterranean recipe that contained dates, raisins, orange juice, walnuts, and other ingredients. For Rosh Hashanah there was dulce, a spoon sweet made from quince and apples, instead of apples dipped in honey. For Hanukkah, the family ate bunuelos, deep-fried fritters served with a simple syrup, and in addition to matzah ball soup, they enjoyed masa en caldo, a chicken soup with softened matzah and lemon, resembling a traditional Greek egg-lemon soup. And bourekas—filled with meat and eggplant, or cheese, and for Fall holidays pumpkin—were a constant presence on the table. This was all true through the 1990s, before Sarah got sick with dementia and in 2009 passed away after years of loving care from her husband, who outlived her only by three months.11

Postscript – Remembrance and Return

In 1984, after Harry graduated from law school, Sarah and Eugene decided it was time to finally show their children their birthplaces, returning to Europe for the first time in decades. Just weeks before the trip, the family’s visas to then Communist Czechoslovakia were summarily denied. But they did make it to Greece, where Sarah was able to show her family the Kavala of her childhood: the family home, her school, the location of the long-since torn down family store, and the picturesque island of Thasos where she spent idyllic summers. It was a bittersweet visit, as the reminders of all that was lost were omnipresent.

In 1992, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Eugene and his family were able to travel to Czechoslovakia. They visited his home village and then to Auschwitz, where the nightmares of his camp experience took form once again. The archives at Auschwitz also revealed the fate of Sarah’s older sister, Allegra: she died in the camp hospital on February 3, 1945, only days after the camp’s liberation, and was buried in a mass grave nearby.

Harry continued to return to Kavala after his parents’ passing. In 2016, he brought his sister Helene, his cousins Debbie and Karen, and their three daughters to Greece and showed them Kavala. All the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Eliezer and Henrietta were together, paying homage to their ancestral home. When he returned again two years later, Harry secured a meeting with the town’s mayor, obtaining her commitment to have a section of the soon-to-be-built municipal museum be dedicated to the history of the Jews of Kavala.

To honor the memory of their parents, Harry and Helene Zinn also established the Sarah and Eugene Zinn Scholarship for Holocaust Studies and Social Justice at the UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies, which, for over ten years now, has awarded scholarships to support student research about the Holocaust.

Citation MLA: Králová, Kateřina. “From Kavala to California: Sarah Haim and Her Family.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/from-kavala-to-california/.

Citation Chicago: Králová, Kateřina. “From Kavala to California: Sarah Haim and Her Family.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/from-kavala-to-california/.

About the Author:

Kateřina Králová is an Assistant Professor and Head of the Department of Russian and Eastern European Studies at Charles University, Prague… More

Citations and Additional Resources

The author would like to express her sincere gratitude to Harry and Helene Zinn, whose assistance was vital to this project, and Jo-Ellyn Decker (USHMM) who helped extensively with the research.

1 On the occupation of Greece, see Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941—44 (New Haven: Yale Nota Bene, 2001); on Bulgarian occupation, see Hans-Joachim Hoppe, “Bulgarian Nationalities Policy in Occupied Thrace and Aegean Macedonia,” Nationalities Papers 14, no. 1-2 (1986): 89-100 and Hans-Joachim Hoppe, “Germany, Bulgaria, Greece: Their Relations and Bulgarian Policy in German-Occupied Greece,” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 11, no. 3 (1984): 41.

2 Violetta Hionidou, Famine and Death in Occupied Greece, 1941-1944 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 25-26.

3 Interview with Laura (Haim) Simon in Woodland Hills, CA, interviewed by Kateřina Králová (January 3, 2016).

4 Ibid.

5 USHMM, RG-68.067M – Illegal Immigration to Palestine: Documents Related to Passengers on the S.S. Henrietta Szold (ID: 19576), Palestine Police Force protocol on Sara Haim (December 18, 1946). See also Hillel Kuttler, “Second-Generation Survivor Sees ‘remarkable Window’ into Past,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency (blog), April 9, 2015.

6 Deborah Dash Moore, To The Golden Cities: Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1996).

7 Mark Wyman, DPs: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945-1951 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998), 147.

8 Interview with Eugene Zinn, 3435, S. 30, time 3:21, USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive accessed at the Malach Centre for Visual History, Charles University Prague with support of the LM2015071 LINDAT/Clarin infrastructure.

9 Meir Zamir, “‘Bid’ for Altalena: France’s Covert Action in the 1948 War in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 1 (2010): 17–58.

10 Eugene Zinn, Auschwitz Memories by Haeftling No. 30113: Manuscript, Claims Conference Holocaust Survivor Memoir Collection (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1994), 1–30.

11 Email correspondence with Harry Zinn conducted by Kateřina Králová (November 12, 2019)

Partial Bibliography

Fleming, Katherine E. Greece – A Jewish History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Hionidou, Violetta. Famine and Death in Occupied Greece, 1941-1944. Cambridge Studies in Population, Economy and Society in Past Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Hoppe, Hans-Joachim. “Bulgarian Nationalities Policy in Occupied Thrace and Aegean Macedonia.” Nationalities Papers 14, no. 1–2 (1986): 89–100.

Kuttler, Hillel. “Second-Generation Survivor Sees ‘remarkable Window’ into Past.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency (blog), April 9, 2015. https://www.jta.org/2015/04/09/lifestyle/second-generation-survivor-sees-remarkable-window-into-past.

Mazower, Mark. Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44. New Haven: Yale Nota Bene, 2001.

Papamichos-Chronakis, Paris. “‘We Lived as Greeks and We Died as Greeks’: Thessalonican Jews in Auschwitz and the Meanings of Nationhood.” In The Holocaust in Greece, edited by Giorgos Antoniou and A. Dirk Moses, 157–80. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey through the Twentieth Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019.

Wyman, Mark. DPs: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945-1951. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Zamir, Meir. “‘Bid’ for Altalena: France’s Covert Action in the 1948 War in Palestine.” Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 1 (2010): 17–58.

Zinn, Eugene. Auschwitz Memories by Haeftling No. 30113: Manuscript. Claims Conference Holocaust Survivor Memoir Collection. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1994.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.