Solomon Nunes Carvalho pointed to two of Los Angeles’ most important attributes in the aftermath of his three-month sojourn there in the summer of 1854: it grew “the most delicious grapes I ever tasted,” and its residents lived on the verge of social chaos. Carvalho’s initial encounter with southern California was pleasant indeed, occurring as it did at the end of a cross-country journey whose myriad physical challenges had nearly cost him his life. His visit to the area restored him to full health. It afforded him the gift not only of its “delightful” climate but the opportunity to practice the Spanish he had learned while growing up in his native Charleston, South Carolina’s Sephardic community. His fluency in Spanish undoubtedly eased his social path in multilingual Los Angeles. In his travelogue he described dancing with “beautiful senoritas” who wore their brown hair in three-foot-long tresses. As a product of the Sephardic diaspora, on the other hand, Carvalho was sensitive to the plight of outsiders. He soon discovered that the city’s stratified and unkempt social atmosphere was hardly a utopian one for all of its inhabitants. Acts of violence occurred there on a daily basis among its mixed population of Indians, Mexicans, Spaniards, and newly arrived Anglo Americans. “Alas,” Carvalho wrote, “for the morals of the people at large. . . It was the usual salutation in the morning, ‘Well, how many murders were committed last night?’” Despite the brevity of his stay in the city, Carvalho’s written recollection of the time he spent there was remarkably prescient. For a select few, Los Angeles would prove to be a Paradise indeed, rife with physical bounties and the tantalizing prospect of the good life. For others, its seemingly wide horizons bore a deceptive mantle. Desperate and risk-taking behavior was the norm, and Carvalho became aware that true power lay in the hands of the tiny minority of its inhabitants who happened to be of “pure” European ancestry. In his role as one of the founders of the city’s permanent Jewish community, he did what he could during his short stay there to counteract the social disorder that had so startled him on his first arrival.

Like many who would follow in his wake, Solomon Nunes Carvalho was an artist whose arrival in Los Angeles coincided with his search after a much needed respite. Born in Charleston in 1815, he had spent his entire life first studying and then practicing painting and later daguerreotype-making in the cities of the eastern seaboard. After a youth spent in Charleston, Solomon would move on, first to Philadelphia (where he studied painting with Thomas Sully, one of the nation’s leading artists) and then to Baltimore and New York, where he opened daguerreotype studios. In 1853, his success as a daguerreotypist came to the attention of John C. Frémont, who hired him as a member of the officer corps on an expedition whose purpose it was to choose and document a potential route for a transcontinental railroad. In order to map the route properly, the group would have to cross the Rockies in the middle of winter. Carvalho managed to get far as Utah before the stress of over-exposure and near-starvation caused his health to give out completely. While he was recovering in Salt Lake City, Carvalho completed a portrait of Brigham Young and apparently felt healthy enough to dance with more than one of Young’s nineteen wives at a governor’s mansion ball. After six weeks in Utah, he continued westward to California. Only “the watchful eye of Divine Providence” would keep him and his fellow travelers alive through the intervening 850 miles, where they encountered such horrors as 40 rotting mule corpses within the space of a mile and where Carvalho underwent “a severe attack of brain fever superinduced by exposure in traveling over hot deserts of sand” across the width of the Nevada territory.

Carvalho’s pointed reference to God’s grace was far from coincidental. He was as thoroughly immersed in Judaism and organized Jewish life as any man of his time in the United States might have been. His family, whose origins lay in Spain, had spent several generations sojourning among the Sephardic communities of the Atlantic world. In the aftermath of the Inquisition, the Carvalhos had spent time in Amsterdam, London, and Barbados, and in each place, they involved themselves in synagogue life and Jewish affairs. Solomon’s mother, Sarah Cohen D’Azervedo, was descended from a noted London hakham, or Sephardic spiritual leader. David Carvalho, Solomon’s father, had played an important role in the development of Charleston’s (and the nation’s) first Reform Jewish congregation. Solomon himself grew up attending services at Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, whose beautiful sanctuary he recaptured in an 1838 painting he completed after the fire that destroyed it. Throughout his life, he participated in, engaged in acts of charity for, and identified himself as a member of the wider Jewish community. In combination with the romantic ethos of the day (this was the age of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman, after all), Carvalho’s traditional Judaism inspired an uplifted rhetoric, as well as a future-oriented social ethic. While he would only spend three months in Los Angeles, the role he would play in the development of its burgeoning Jewish community had a lasting impact. Both in his writing and in his acts of community-building, Carvalho exemplified what two historians of the California Jewish experience have described as a characteristic mindset whose upholders “contributed to a sense of permanence and stability in settlements that had grown up overnight.”

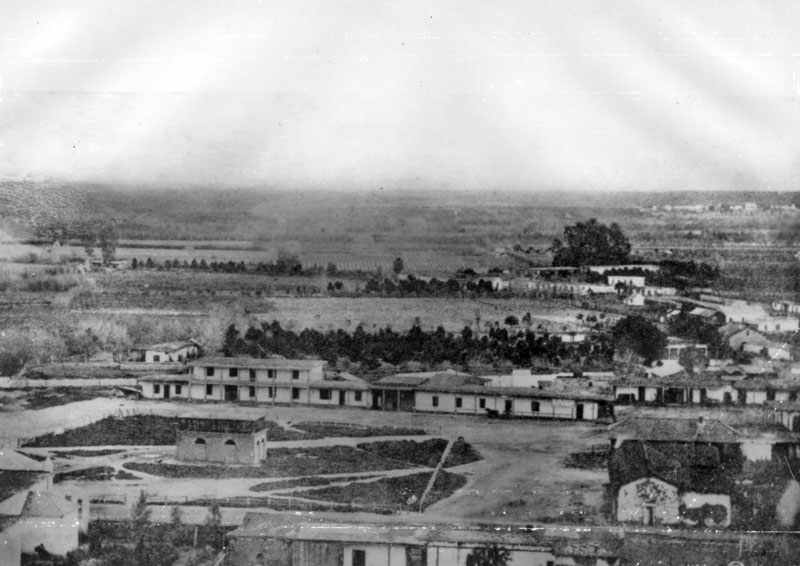

In 1854, the idea that Los Angeles would end up becoming the nation’s second largest city, let alone the home of the fourth largest Jewish population of any city in the world, would have been all but inconceivable. In 1850, it was a tiny settlement whose total population was less than 2,000. Carvalho entered the region by way of Cajon Pass, above San Bernardino, on the descent from which he “rode through a beautiful grove of cottonwoods . . . [and] rose trees in full bloom, with hundreds of beautiful flowers.” Upon his first arrival in the “fairy land” of southern California, he spent ten days recovering from his brain fever at the ranch of Don Manuel Domingues, “a noble specimen of a Spanish gentleman” (as had been the case for him in Salt Lake City, his recuperative activities included the aforementioned dancing with the “beautiful senoritas”).

Carvalho then became a guest of his fellow Sephardim, Samuel and Joseph Labatt, who had come to California from New Orleans and opened an upscale store on Main Street they called La Tienda de Chine (The China Store). There they sold men’s suits, jewelry, accordions, and other luxury goods. During his period of residency at the Tienda, Carvalho opened a painting and daguerreotype studio on its second floor. It was also in his capacity as a guest of the Labatt brothers that Carvalho would act out his role as one of the founders of Los Angeles’ Jewish community.

While San Francisco’s Jewish community had been growing steadily ever since the gold strikes of the 1840s, Los Angeles experienced a more gradual expansion. When Carvalho arrived there, only 30 or so Jews could be found in all of southern California, and there had been no organized attempt to create a community. Against the backdrop of the city’s then vast and only sparsely settled open spaces, it was hard to imagine a permanent future for any community that privileged tradition and communitarianism. Even in the comparatively staid atmosphere of San Francisco, as Carvalho wrote in his memoir, “hundreds of men who have acquired by hard work and industry a little fortune at the mines” found it impossible to resist the temptations of gambling and quite frequently “lost the labor of months” as a matter of course. Nonetheless, on July 2, 1854, as it would eventually be reported in The Occident (the nation’s only Jewish newspaper of the period), the Los Angeles “Israelites . . . formed themselves into a society under the name of the Hebrew Benevolent Society.” Carvalho had apparently been instrumental to this endeavor, and the Society commemorated his participation by electing him as an honorary member and enshrining his actions in print. The Society acted quickly to establish a burial ground and a philanthropic fund. It also took its first steps towards founding an actual synagogue.

Citation MLA: Hoberman, Michael. “Carvalho in Los Angeles.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/carvalho-in-los-angeles/.

Citation Chicago: Hoberman, Michael. “Carvalho in Los Angeles.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/carvalho-in-los-angeles/.

About the Author:

Michael Hoberman is Professor of English and American Studies at Fitchburg State University… More

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.