On July 4, 1905, some 40,000 L.A. residents gathered to celebrate the opening of a new beachfront resort named “Venice of America,” with an elaborate system of canals and a central lagoon, a mile-long boardwalk along the sand, and a 1700-foot-long pier extending into the ocean (still under construction at the time). The celebration marked the finale of a years-long effort by Abbot Kinney, a tobacconist and real estate developer, who had grand ambitions for the project: in Venice, he hoped to create a site of artistic creativity and intellectual innovation in the mold of its namesake in Italy that could serve as the wellspring of an American Renaissance. In its 5,000-seat auditorium, he would host lectures by cultural luminaries, performances by visiting symphonies, and Chautauqua-style adult education programs, creating opportunities for enlightenment and self-improvement available to all Angelenos. Opening day’s festivities included live music and dancing, art exhibitions, “patriotic addresses” by revivalist Benjamin Fay Mills and journalist William E. Smythe, gondola rides on the canals (with gondoliers brought in from Italy), and swimming and diving contests in the lagoon, all culminating in an elaborate fireworks show.1

Much to Kinney’s dismay, however, very few of the visitors to his new resort in its early days were interested in such refinements and his adult education program lost some $16,000 (almost $500,000 in today’s currency) in its first year.2 Instead, what drew most visitors to Venice was a decidedly lower-brow affair: the Midway Plaisance, an assemblage of novelties, curios, and theaters on the east side of the lagoon. Towering above these attractions were the two turreted, striped minarets marking the entrance to the “Streets of Cairo,” the main feature of the Midway, a network of narrow streets – each named for an eastern capital such as Constantinople, Tunis, and Algiers – where visitors could ride camels, take pictures with Turkish sword-swallowers, catch a glimpse of genuine mummies imported from Egypt, or purchase any number of “oriental” treasures. In its central plaza was a domed Moorish-style theater that was home to the eponymously named “Streets of Cairo” show, an “oriental” cabaret featuring “hoochee-coochee” dancers Madame Fatima and Princess Rajah. Blending the exotic and the erotic, the carnivalesque spectacle of the “Streets of Cairo” and the Midway Plaisance transformed “Venice of America” from a site of high culture and enlightenment into Los Angeles’ most popular destination for pleasure-seeking.

The man behind the Midway was a renowned showman named Gaston Akoun, who had earned international acclaim for his work as a producer of exposition entertainments. Born to a Jewish family in Algiers, Akoun first came to America in 1893 to work in the “Turkish Village” concession at the World’s Fair in Chicago and then became a regular feature of the circuit, producing “Streets of Cairo” style attractions at the World’s Fairs in Omaha (1898), Buffalo (1901), St. Louis (1904), and Portland (1905), before coming to Los Angeles in 1905. After building the Midway at “Venice of America,” Akoun moved to Paris where he developed Luna Park, the first amusement park in the city, which he managed until France fell to the Nazis, escaping to New York where he died in 1943.

While Abbot Kinney’s role in Venice has been well commemorated, Gaston Akoun’s contributions have been all but forgotten since his “Midway Plaisance” was torn down and replaced by a roller coaster in 1911. But with his “Streets of Cairo” attraction, Akoun helped to incorporate Los Angeles into an international marketplace of “oriental” consumption – of goods, culture and entertainment – a marketplace that brought many “eastern” Jews to the United States for the first time. Recovering the story of his life and career opens a vital window into the shifting landscape of tourism, leisure and consumption in early twentieth-century American life, and the unlikely place of North African Jews within it.

Oriental Jews and the World’s Fair

Stretching over 600 acres along banks of Lake Michigan, the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago was designed to celebrate the advances made in technology, industry, philosophy, and society in the four centuries since Columbus first “discovered” America. The official fair grounds, a collection of over 200 ornate neoclassical and Beaux Arts buildings known as the White City, monumentalized American progress, presenting a spectacle of splendor and stately grandeur that positioned the United States at the pinnacle of western civilization.

Located beyond the gates of the White City, the Midway Plaisance offered visitors to the World’s Fair in Chicago a different sort of human spectacle. There, visitors could sample in the cultures of far-away-lands by visiting a variety of indigenous “villages” featuring exotic “native” inhabitants from all over the world who often staged live performances of the unique dances, musical traditions, and fighting styles of their homelands in elaborate costumes. While the White City showcased technological progress and cultural refinement, the Midway offered visitors a glimpse of the “primitive” cultures of peoples untouched by modern life: thatched bamboo huts where “Javanese” men fashioned blow pipes, an encampment of sword-wielding “Bedouins” and their caparisoned horses, and an “Eskimo village” where the sealskin-clad occupants demonstrated fishing and hunting techniques. The “real life” foreign bodies on display – in situ performances of cultural, racial, and ethnic difference – gave the villages of the Midway a patina of authenticity that the artifacts on display in the White City lacked, offering visitors not simply an education but an opportunity to conduct their own anthropological fieldwork.

Originally under the direction of anthropologist Frederick W. Putnam, director of Harvard’s Peabody Museum, the development of the Midway was quickly taken over by an ambitious young theater producer named Sol Bloom, who proposed the creation of something far more entertaining and lucrative. As he described in his autobiography, Bloom had been inspired by a visit to the “Algerian Village” at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1889, which featured “dancers, acrobats, glass-eaters, and scorpion swallowers” unlike anything he had ever seen. While he doubted that the exhibition was an accurate reflection of Algerian culture, as he described, “what was really important was that they presented a varied entertainment that increased excitement in proportion to my familiarity with it.”3 Under his management, the educational impetus of the Midway became secondary to interests in novelty, foreignness, and spectacle. Mixed in among the “village” displays were ethnic markets, rides, and other attractions – including the world’ first Ferris wheel – blurring the lines between popular entertainment and ethnography. The Midway became a cacophonous and colorful “marketplace of pleasure” that stood in contrast to the ordered sophistication of the White City, constructing within the landscape of the fairgrounds hierarchies of civilization and savagery, propriety and decadence, and progress and backwardness that reinforced white racial superiority and America’s increasing imperialist ambitions.4

In keeping with Bloom’s original inspiration, the “oriental” cultures of North Africa and the Middle East figured prominently on the Midway, showcased in several “villages” with decorative architectural installations, bazaars, and theaters. As Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and others have shown, Jewish merchants and performers from Ottoman lands played significant roles in these oriental displays, even if they were not always identifiable as such.5 These included Robert Levy, a Sephardic “Oriental Goods” dealer from Istanbul, who won the contract to create “village” style installations to represent the Ottoman Empire on the Midway. He secured authorization from the Ottoman Ministry of Trade and Public Works to construct a scaled reproduction of Sultanahmet Square in Istanbul, complete with a replica obelisk and mosque (based on the world famous “Blue Mosque”), surrounded by “luxurious pavilions, expensive furniture and decoration, sedan bearers, Persian tent, bazaar with forty booths, candy factory with Oriental sweets [and] refreshments.” Levy, identified in the local press as “the Sultan’s representative,” often sported elaborate “oriental” costumes that bolstered his Ottoman bona fides.6

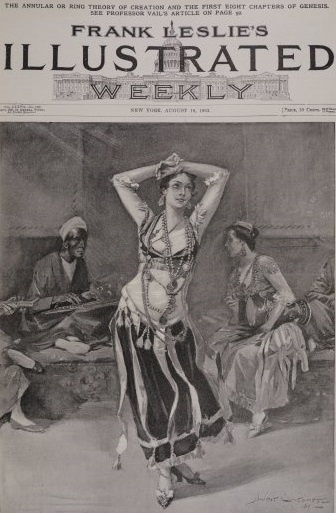

This “oriental” scenery served as a marketplace for merchants and vendors as well as an outdoor stage for a dazzling array of performers – whirling dervishes, sword swallowers, jugglers, musicians, and camel riders – who served as the “native” village residents. To assist with the complicated bureaucratic navigation required for bringing those “natives” to Chicago, Robert Levy, along with Dr. Cyrus Adler, a Semitics scholar enlisted as the World’s Fair Commissioner to Turkey, Palestine, Persia, Egypt, Tunis, and Morocco, worked closely with L’Alliance Israélite Universelle, a French-Jewish philanthropy with an extensive network of Jewish schools throughout the Middle East and North Africa. The Alliance helped to recruit craftsmen, artists, and merchants and as a result, by one estimate, nearly 80 percent of the inhabitants of the Turkish Village were Jews.7 These included the stars of the village’s most buzz-generating feature: the tantalizing dancing girls of the Turkish Theater and its headliner, “La Belle Rosa.” Produced by Sol Bloom himself, the “Streets of Cairo” show, which purported to showcase regional dance styles from across the “orient,” primarily attracted attention for the risqué “danse du ventre” (belly dance) that La Belle Rosa, billed as “The World’s Greatest Oriental Dancer,” and other women performed. Exotic in both the sensual eroticism of the performance and the physiques on display, the “Streets of Cairo” show came to embody the oriental allure of the Turkish village as a whole.

The young Gaston Akoun was among the “oriental” Jews recruited to work in the “Algerian Village” at the Columbia Exposition in Chicago. The details of his biography are difficult to disentangle from his self-promotional puffery, but according to passport applications, he was born in Algiers in 1875, decades after France had seized the territory from the Ottoman Empire. The French colonial government dismantled the dhimma system that governed relationships between Muslims and non-Muslims under the Ottomans to incorporate Algerian Jewish communities into the Central Consistory of the Jews of France, which afforded Akoun and other Jews in Algiers access to a French-language school system – designed to “regenerate” the “backwards” Jews of Algeria – and, following the passage of the Crémieux decree in 1870, to the rights and protections of French citizenship.8 At some point in his childhood, Akoun, perhaps with his family, moved to Paris, and in 1891, he departed from Le Havre for the United States. While in subsequent years Akoun would falsely claim to have been responsible for producing both the original “Algerian Village” in Paris and the “Streets of Cairo” show in Chicago, he learned one clear lesson from his experiences at the World’s Fair: he could make a career for himself in America by engaging with his “orientalism.”9

In 1895, when he was just twenty years old, Akoun opened his first attraction on Coney Island, “The Streets of Cairo,” which featured an “oriental bazaar,” camel rides, and the eponymously named danse du ventre cabaret. He was not the first to bring the show to New York: it had premiered at the Grand Central Palace in 1893, where, at the request of anti-vice crusader Rev. Charles Parkhurst, the police had shut it down and arrested the performers for immoral conduct. Akoun launched his “Streets of Cairo” attraction in the wake of the trial that ensued, capitalizing on the public curiosity engendered by the sensational, and often bemused, press coverage, and hiring two of the arrested dancers, Ferida (Fahreda Mazar Spyropoulos) and Fatima (Fatima Djemille), both veterans of the 1893 World’s Fair who, at varying times, performed under the stage name of “Little Egypt.” As in Chicago, these women’s undulating bodies – exotic and salacious in their “eastern” eroticism – served to authenticate the “Streets of Cairo,” attracting thousands of visitors as well as the attention of local law enforcement, who again shut down the show and arrested the performers in 1896. But by then, the danse du ventre was known as the “hootchee cootchee,” a popular feature of burlesque and vaudeville shows performed by white American and “oriental” women alike.10

Sol Bloom would later claim in his autobiography that Little Egypt and her “reputed stage appearances in the nude” were “bastard version[s] of the danse du ventre” which he had brought to the United States.11 But his efforts to police the boundaries of decency and authenticity of those performances were premised on the same imperialist logic as the World’s Fair itself: unless such displays of “oriental” culture were intermediated by American concessioners like him, those “native” bodies would revert to their “primitive” and “uncivilized” ways. By orchestrating a show of their own, Akoun and the North African and Eastern Mediterranean performers he employed usurped those hierarchies of civility and race, his “Streets of Cairo” attraction at Coney Island providing a means for him and other veterans of the World’s Fair to take control of their own cultural capital and position themselves within a global marketplace of pleasure and consumption by “playing eastern.”12

Gaston Akoun, “The Mighty Man of the Midway”

From Coney Island, Akoun took his “Streets of Cairo” attraction to the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha in 1898. The Omaha Fair was intended to replicate the model set in Chicago but with an emphasis on “the products, industries and civilization of the states west of the Mississippi river.” Accordingly, much of its educational focus was placed on “natives” of the west – American Indians – with a special $40,000 fund allotted by Congress to create an “ethnological exhibit” featuring representatives of over three-dozen tribal groups.13 As a result, Omaha’s Midway was mostly comprised of rides and games, rather than international “villages,” and Akoun’s concession, which he renamed “The Streets of All Nations,” was the largest and most elaborate of those that remained. He built a system of interconnected streets and courtyards lined with oriental goods bazaars and cafés, as well as a replica mosque and two theaters in classical Greek and “oriental” styles. Both indoor venues and outdoor spaces served as stages for a large troupe of performers: Akoun secured passage from the French government for “a large consignment of camels, donkeys, and Arabian horses” as well as their handlers, sword fighters, a family of acrobats, and a group of “twenty-five women, natives of Algeria” for whom he had to pay deposits of 1000 francs “as a guarantee for their safe return.”14 He built walls around his attraction to separate it from the others nearby, erected two elaborate Egyptian-temple style gates, and charged a separate fifteen-cent entrance fee. Removed of its demand for indigenous “authenticity” within the “Streets of All Nations,” one could find “natives” from across North Africa and the Middle East in a broad spectrum of “oriental” costuming, from robes and kufiya (head scarves) to vests and tennure (whirling skirts) to three-piece suits with Ottoman-style fezzes.

After Omaha, Akoun took his act to the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901, where he planned an even larger attraction that he called “The Beautiful Orient.” Comprising over 175,000 square feet, Akoun built eight streets – each “a faithful reproduction” of an oriental capital including Istanbul, Tunis, Algiers, Tehran, Cairo, and Tripoli – extending out from a central courtyard that housed a replica of the Mosque of Al-Azhar in Cairo. He assembled some 800 people to fill these streets, including over 120 vendors and performers that included “a troupe of genuine red warrior Spahis [cavalrymen] showing wild riding…sword contests, Hindoo jugglers, wrestlers, gun spinners, dancers, acrobats, torture dancers, and snake charmers.” Once an hour, these performers paraded to the gates of the “Beautiful Orient,” where they beckoned would-be visitors against a backdrop composed of minarets, Greek flags, obelisks adorned with hieroglyphics and a giant sphinx. As one guide to the Fair described, with its “oriental buildings, costumes, racial peculiarities, bona fide natives, [and] animals,” the Beautiful Orient had “all of the glittering paraphernalia necessary to transplant a section of the mystical East in the very heart of the prosaic West.”15 For this achievement, officials in Buffalo dubbed him one of the “Mighty Men of the Midway – Gentlemen Showmen who Amuse and Instruct Multitudes.”16

In his “Beautiful Orient,” Akoun had expanded far beyond the tantalizing eroticism of the “Streets of Cairo” show, subsuming both the ethnographic and the commercial impetuses of the Chicago Midway to consecrate a new kind of pleasure-seeking experience. He created a sort-of orientalist theme park, a mélange of exotic architectural wonders, performances, and cultural delights that took visitors who lacked the means for (or the interest in) world travel on a tour through the “mystical East.” His attraction collapsed divergent ethno-religious traditions and distances of geography and time into a singular “Orient” that was both beautiful and consumable, both exotic and accessible. By presiding over it, Akoun – who identified himself as French or Parisian (rather than as Algerian or Jewish) in his promotions – fashioning himself a modern, Westernized citizen of an empire that had taken possession of the wonders of the ancient East, an authorial intermediary to this vast “Beautiful Orient.”

Akoun expanded the scope of his “Orient” even further at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904, adding “streets” to represent Delhi and Calcutta, with replicas of the Taj Mahal and the Rain Sipri Mosque in Gujarat, elephant rides, and performers from Sri Lanka and Burma. He formed a close relationship with another Algerian Jewish concessioner, Mordecai Zitoun, the general contractor of the Jerusalem Exhibit who built a scale model of the “Old City” in St. Louis that included the Jaffa Gate, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Ecce Homo archway, and the Mosque of Omar.17 His younger brother Ferdinand Akoun, who had joined him in Buffalo, also opened his own attraction – a fun house with a maze of mirrors – helping the Akouns to build relationships with other long-time concessioners. Together, they travelled to Portland the following year for the Lewis and Clark Exposition, where Zitoun was part of the French delegation and Akoun, who had become a naturalized American citizen, served as commissioner of the official Oriental Building, which included Japanese, Chinese, Egyptian, Persian, and East Indian sections. He also built an adjoining “Oriental Village,” where the danse du ventre made its West Coast debut.

Akoun brought all of these commercial and personal relationships to bear in Los Angeles, where his newly formed Akoun Amusement Syndicate purchased rights to build a permanent Midway Plaisance at Venice Beach. Mordecai Zitoun came along to serve as manager of the attraction and, in subsequent years, became a founding member of the local Sephardic community, known affectionately as “Papa.” Akoun also invited Yumeto Kushibishi, commissioner of the Japan exhibit in Portland, to build his own oriental market, as well as other concessioners who had been part of the original Midway in Chicago, such as Carl Hagenbuck and his exotic reptile and live animal show, and the proprietors of “Darkness and Dawn,” a haunted house ride based on Dante’s Inferno and “The Temple of Mirth,” an elaborate fun house. But once again, Akoun’s “Streets of Cairo,” with its camel rides and oriental cabaret, was the biggest draw: as a testament to the show’s popularity, Princess Rajah, dubbed by the LA Times as the “high priestess of the voluptuous wriggle,” was chosen to represent Venice in the city’s annual “La Fiesta” parade in 1906, dancing while she rode a top a camel pulling one of the gondolas from the canals.17

Beyond the Midway

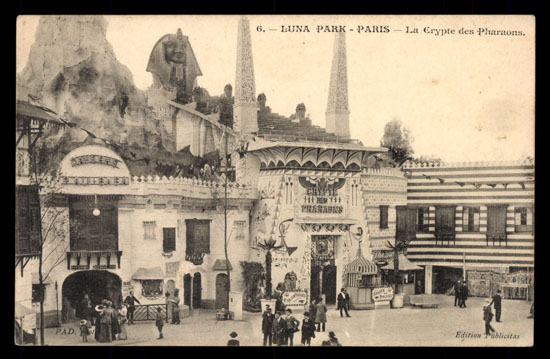

Gaston Akoun’s time in Los Angeles was short lived: almost as soon as his Midway Plaisance in Venice was completed, he began preparations to build a “Beautiful Orient” attraction at the Jamestown Exposition in 1907. Kinney filed a lawsuit to prevent Akoun from taking the “Streets of Cairo” with him, but the dispute may have worked to Akoun’s advantage, as the fair in Jamestown was a financial disaster for all of those involved.18 Akoun instead returned to Paris, where he began construction on Luna Park, the first “American-style” amusement park in the city. Described in the French press as “une ville enchantée” featuring “folies, tivolis et attractions,” Luna Park had at least one “oriental” element: the “Crypte des Pharaohs,” a haunted house filled with mummies, decorated with sphinxes, obelisks inscribed with hieroglyphics, and other Egyptian motifs.19

Abbot Kinney dismantled the Midway Plaisance in 1911 to make way for a new attraction: a roller coaster called “A Race Through the Clouds.” He and his investors had by then learned a clear lesson from Akoun: instead of a site of high culture, self-improvement and education, Venice would be a destination for cheap thrills and amusements. On the pier, they added a carousel, Ferris wheel, and airplane ride, as well as an ostrich farm and aquarium and dozens of carnival games, many of which burned down during a massive fire that destroyed the pier in 1920, just a month after Kinney’s death. Financially devastated, the City of Los Angeles took possession of much of the Kinney Company’s land, gradually filling in the canals and opening the area to new residents and oil drilling. In 1946, the same year that Akoun’s Luna Park closed in Paris, the city refused to renew the Kinney’s company’s lease, officially incorporating the area as a new neighborhood within the city named Venice Beach.

But even as the landscape changed, the human spectacle that Akoun had created in “The Streets of Cairo” endured as a fundamental part of the experience in Venice. From the gymnasts and body builders of “Muscle Beach,” to beauty contestants and roller skating girls, to beatniks and scantily-clad hippies, and surfers and skate boarders, tourists continue to flock to Venice to ogle at the exotic bodies on display, the boardwalk providing a sort of ethnographic tour of the “natives” of Southern California. Venice remains a cacophonous and colorful “marketplace of pleasure” that blends of novelty, spectacle, sensuality, and consumption, a vestige of the Midway Plaisance Akoun built there a century ago.

Citation MLA: Luce, Caroline. “‘Oriental’ Jews on the Frontier of Leisure.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/frontier-of-leisure/.

Citation Chicago: Luce, Caroline. “‘Oriental’ Jews on the Frontier of Leisure.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/frontier-of-leisure/.

About the Author:

Caroline Luce is the Associate Director of the UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies … More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 “Throng Storms Fair Venice,” Los Angeles Times, July, 1905, I10.

2 Jeffery Statton and Annette del Zappo, Venice California: 1904-1930 (Venice, CA: ARS Publications, 1978): 28.

3 Bloom, Sol, Autobiography of Sol Bloom (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Son, 1948), 107.

4 L.G. Moses, “Indians on the Midway: Wild West Shows and the Indian Bureau at the World’s Fair, 1893-1904,” South Dakota History 21 (1991): 216.

5 Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, “A Place in the World: Jews and the Holy Land at World’s Fairs,” in Encounters With the “Holy Land”: Place, Past and Future in American Jewish Culture, ed. Jeffrey Shandler and Beth S. Wagner (New York: Center for Judaic Studies, 1997), 60–82; Julia Phillips Cohen, Becoming Ottomans: Sephardi Jews and Imperial Citizenship in the Modern Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 45–73; Milette Shamir, “Back to the Future: The Jerusalem Exhibit at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair,” Journal of Levantine Studies 2, no. 1 (2012): 93–113; Keith P. Feldman, “Seeing is Believing: U. S. Imperial Culture and the Jerusalem Exhibit of 1904,” Studies in American Jewish Literature 35, no. 1 (2016): 98–118.

6 Julia Phillips Cohen, “Oriental by Design: Ottoman Jews, Imperial Style, and the Performance of Heritage,” American Historical Review 119 no. 2 (2014): 364-398.

7 Alma Rachel Heckman and Frances Malino, “Packed in Twelve Cases: the Alliance Israélite Universelle and the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair,” Jewish Social Studies 19, no. 1 (2012): 53-69. The 80 percent statistic comes from Isidor Lewi’s essay “Yom Kippur on the Midway,” as quoted in Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, “A Place in the World,” 68.

8 Aron Rodrigue, French Jews, Turkish Jews: The Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Politics of Jewish Schooling in Turkey, 1860-1925 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 4, 9, 75.

9 Julia Phillips Cohen, “The East as a Career: Far Away Moses & Company in the Marketplace of Empires,” Jewish Social Studies 21, no. 2 (2015): 35-77.

10 Details on these dancers and their arrests appear in Cait Murphy, Scoundrels in Law: The Trials of Howe & Hummel, Lawyers to the Gangsters, Cops, Starlets and Rakes Who Made the Gilded Age (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2010). See also Donna Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt (Bloomington: International Dance Discovery, 1995) and Andrea Deagon, “Dancing at the Edge of the World: Ritual, Community and the Middle Eastern Dancer,” Arabesque 20, no. 3 (1994): 8-12.

11 Bloom, Autobiography of Sol Bloom, 136.

12 Cohen, “East as a Career,” 35-40.

13 “Official Guide Book to Omaha, Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, 1898.”

14 “STILES HAS DEPARTED – The Promoter of the British Empire Exposition Scheme Not in Evidence,” San Francisco Call, March 20, 1896.

15 Ins and Outs of Buffalo… the Queen City of the Lakes… A Thoroughly Authentic and Illustrated Guide (Buffalo: A. B. Floyd, 1899): 181-182.

16 Snap shots on the Midway of the Pan-Am expo, including characteristic scenes and pastimes of every country there represented… ed. Richard Barry (Buffalo: R.A. Reid, 1901): 79.

17 “Sandy Sees the City’s Sights,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1906; “Never Before Such a Parade,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1906. Accessed at ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

18 The lawsuit appears in “Venetian Ripples,” Los Angeles Times, June 5, 1906.

19 Cathie Bryan, “Egypt in Paris: 19th Century Monuments and Motifs” in Imhotep Today: Egyptianizing Architecture, ed. Jean-Marcel Hubert and Clifford Price (London: UCL Press, Institute of Archeology, 2003). See also Michèle Pedinielli, “Le Luna Park, histoire du premier parc d’attractions parisien” Retronews Jan. 2, 2018 accessed at Retronews.com.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.