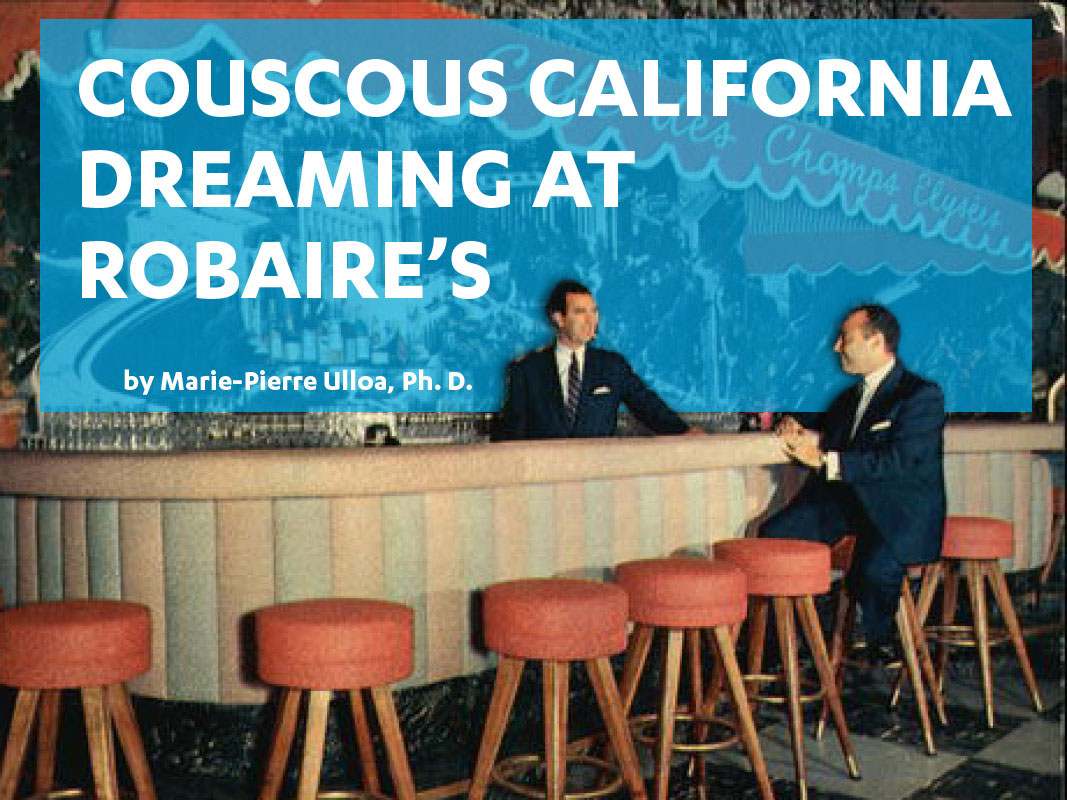

In the years after World War II, North African Jewish immigrants became the mediators and re-inventors of French culture and cuisine in California through the restaurant and hospitality business. This essay explores how Tunisian Jewish migrant Robert “Papouche” Robaire introduced couscous to generations of Angelenos at his French restaurant Robaire’s (1952-1990).

French Cuisine Cachet in Los Angeles

Jews are indigenous to North Africa, and lived alongside the Berbers, or Amazighs, and the Arabs for centuries. When the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, and later from Portugal, many fled to Morocco and to North Africa under Ottoman rule, further increasing the Jewish presence in those lands. With the French colonization of the Maghreb in the nineteenth century, some North African Jews gradually distanced themselves from the indigenous Arab and Berber populations, aligning with the French colonizers, adopting French Republican ideals and French culture and cuisine. Starting after World War II, cuisine and culinary rites represented a powerful identity marker that brought North Africans immigrants in California together, whether Maghrebi Jews, Muslims, Arabs, Berbers, descendants of Harkis or of pieds-noirs,1 migrants rooted in Arabophone and Francophone cultures, and beyond. In turn, the North African immigrants themselves became the mediators and the re-inventors of French soft power in California at their restaurants and small businesses. Their mastery of French culture and cuisine gave them a major symbolic capital; in turn, one of the ways they marked their identities as California Sephardim was to introduce French cuisine to the state. To name a few, Claude Rouas’s L’Etoile was the French restaurant of San Francisco from the 1960s to the late 1980s, while his brother Maurice Rouas was the owner of the Michelin-starred French restaurant Fleur de Lys (a symbol of French royalty) from 1970 to 2012. While they excelled at promoting French cuisine, they usually reserved Maghrebi cuisine for the home, with a major exception: the French restaurant Robaire’s in Los Angeles (1952-1990), owned by Robert “Papouche” Robaire, a North African Jew from Tunis.2

Robert “Papouche” Haddad was born into a Jewish family in Tunis in 1922 when Tunisia was under the French Protectorate. When the Allied forces invaded, and subsequently occupied, the French territories of North Africa during World War II, he became acquainted with American soldiers who came to his family’s restaurant, Chez Paul, and, after the war’s end, decided to immigrate to the United States.4 He arrived in Los Angeles in 1949, where he stayed with Gérard Uzan, a boyhood Jewish friend.5 Robert quickly found work thanks to the French network and a bit of luck as he tells it:

“When I got here in 1949, I went to the consulate to look for work, and the lady there informed me that the consulate was not a job agency. I see a gentleman there, and the lady says to me, “That’s the Consul.” And he turns and says, “Robert, what the hell are you doing here?” It turns out that the Consul was a school supervisor at the Lycée Carnot, where I went to high school. One of the detention punishments for bad behavior involved having to go to school on Sunday and write five hundred lines from Victor Hugo, and he was the one who kept watch. He told me that he had a charming Tunisian friend in need of company, and that I should go see him, that this guy would be thrilled to meet me. “Do you have a car?” he asked. I didn’t, so he lent me his, since he only used it on weekends. So, I went to meet the guy, and we instantly became best friends, Gérard, Slimane and me. We got together every Sunday. Slimane had already been in the US for fifteen years. Everyone here called him Monsieur André. He was a chef. He worked for a restaurant called California BBQ Chicken.”

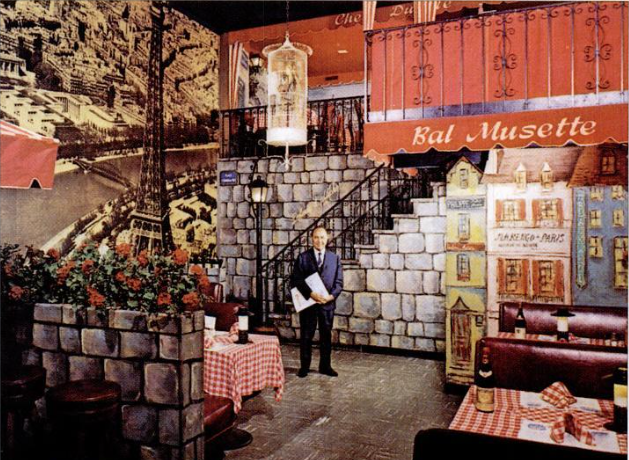

Robert “Papouche” Haddad was naturalized in 1954 and changed his name to Robert Robaire, and his wife Mona, also a Jew from Tunisia, in 1958. The menu at Robaire’s was deeply rooted in traditional French cooking and earned the bulk of the establishment’s reputation. Owed to the restaurant’s proximity to Hollywood, celebrities came to dine there often: William Holden, Barbara Stanwyck, Jean Renoir, Marilyn Monroe, Louis Armstrong, Ginger Rogers, and the writer and World War II veteran, Romain Gary. Gary was a regular for these special couscous nights, and on other occasions as well, when he was the French Consul General in Los Angeles (1956-1960), married then to New Wave icon, the actress and activist Jean Seberg.

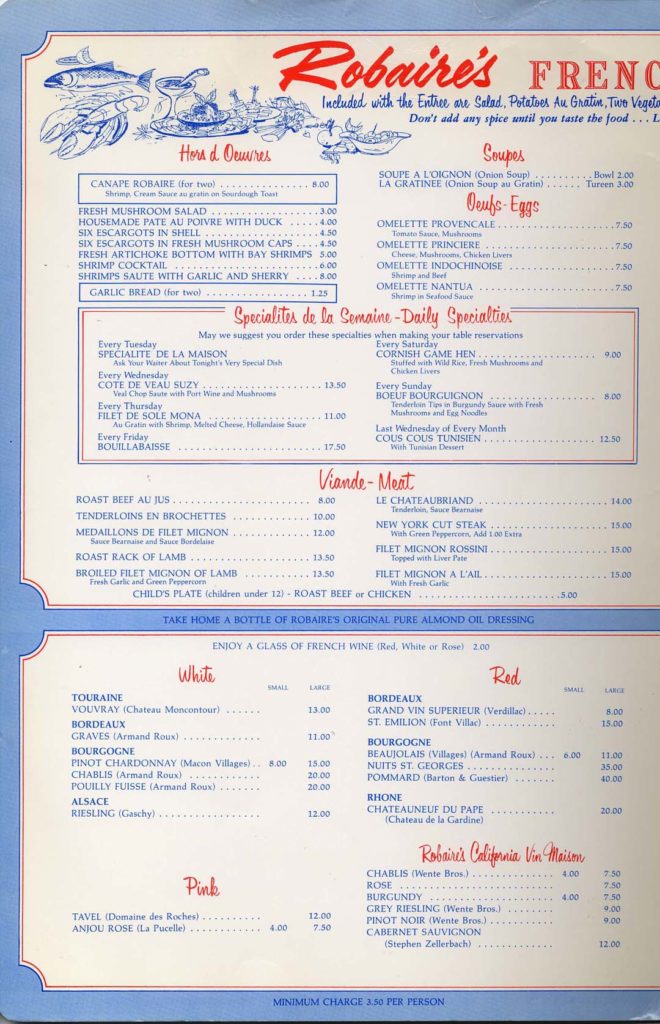

Robaire’s offered a veritable sampler of archetypical French cuisine, which was less exotic for the local clientele than the couscous, which catered especially to their Francophone patrons. A framed copy of their 1963 menu hangs on the Robaire’s living-room wall, among paintings by Mona’s father, the painter Maurice Bismuth.6

Listed on the menu are: Chateaubriand, $3.50. Filet mignon, $3.75. Sole meunière, $1.75. Asked to comment on the menu during my first visit in 2014, Robert Robaire had this to say:

“I don’t mean to brag, but I contributed in a major way to educating Californians about French cuisine. But I went a little far sometimes, when I tried frog legs and snails, which were practically thrown back in my face! (laughter). My mother helped me when I first tried some Tunisian cuisine, with olive oil. Everyone hated it. She made stuffed eggplant, stuffed peppers, a potato ragout, a kind of Tunisian cassoulet. People were afraid to try it. They had to be educated, not re-educated.”

This is then how Mona and Robert narrate the “couscous challenge”:

“Mona: Papouche introduced couscous thanks to some veterans, former G.I.s. When they found out that Papouche hailed from Tunisia, they asked: “So, where’s the couscous, then? We had couscous in Tunisia and loved it.” That’s when we started serving couscous once a month.

Robert: We would sell one hundred servings on the last Wednesday of every month, which meant we also needed one hundred servings of artichoke meatballs to go along with the couscous. I was the first in the city to introduce couscous on a restaurant menu in LA. I had to order in the grain from New York from a Moroccan or Tunisian Jew, who had also started serving couscous in restaurants.”

The role of the American G.I.s on the avant-garde outpost of this new culinary movement cannot be overstated: Robert would not have dared to include the new items on the menu without their insistence. California’s massive defense plants and military bases–owed to its proximity to the Pacific theater–brought many American G.I.s to the state for the first time, thousands of whom returned to the state in the postwar years to realize their golden dreams. Having been exposed to French and North African flavors during their service, they too became the gastronomic mediators of the burgeoning French culinary scene throughout California. As with Robaire himself, Claude Rouas–a French-born Jew from Oran whose family dynasty of French restaurants in the San Francisco Bay Area included the prestigious Auberge du Soleil–came to California in the early sixties because America came to him first, in the shape of the American G.I.s soldier during World War II in Oran. Several decades later, his daughter Bettina Rouas, born in California, opened her French countryside-inspired restaurant, Angèle in Napa, bearing the name of her paternal French North African Jewish grandmother, and featuring the Mauresque cocktail on the list of drinks. The cocktail is the only trace of the North African past of Bettina Rouas’s family on the menu. The Mauresque cocktail takes its name from the history of the French conquest of Algeria starting in 1830, when French soldiers in the Arab Bureau stormed and occupied Algeria.7

Cooking the Tunisian Jewish Way

Robaire’s only concession to his Tunisian palate, aside from the Tunisian desserts, was his “Double-Steamed” couscous with Artichoke Meatballs, served on the last Wednesday of every month at Robaire’s. The dish was a long-running success and his legacy in many ways. Indeed, couscous came to earn the restaurant part of its reputation, as one faithful patron told the Los Angeles Times in 2005:

“I enjoyed the well-researched and gloriously illustrated article on couscous [“Marrakesh Express,” Oct. 5]. However, I was shocked that it didn’t mention Robaire’s French restaurant on La Brea. Robert Robaire was undoubtedly the first to serve “double-steamed” couscous in Los Angeles, going all the way back to the early 1950s. As a longtime patron of Robaire’s, from the early 1970s until it closed in 1990, I have fond memories of the Tunisian couscous sumptuously served the last Wednesday of every month. Incorporated in the dish was a delicious, lighter-than-air meatball stuffed with an artichoke heart, as well as lamb, chicken and vegetables served with a broth. The couscous was wondrously fluffy because it was double-steamed under the watchful eyes of Robaire, his wife, Mona, and her mother, who brought the recipe from Tunis. It was the best I’ve ever tasted and the benchmark for all others.”8

The couscous was prepared first by Robert Robaire’s own mother, then by his mother-in-law, then by his wife. There is indeed a distinctive trait when it comes to North African Jews involved in gastronomy in Los Angeles and in California: the gender (im)balance. The men are the owners and managers of restaurants, and the women are in the kitchen, such as at Robaire’s. The men are the visible faces of the restaurant and tend to be the ones getting the credit, and the women do the labor behind the doors, with helpers. It is also the case at Koutoubia, another Jewish North African restaurant opened in 1978 by a friend of Robaire, Michel Ohayon, originally from Marrakech, which is still in business today.9 There the owner’s mother and wife prepare the Moroccan couscous, and other North African specialities (renaming them “tagine berbère, couscous fassi, couscous chaoui, tagine d’agneau M’Rouzia”).

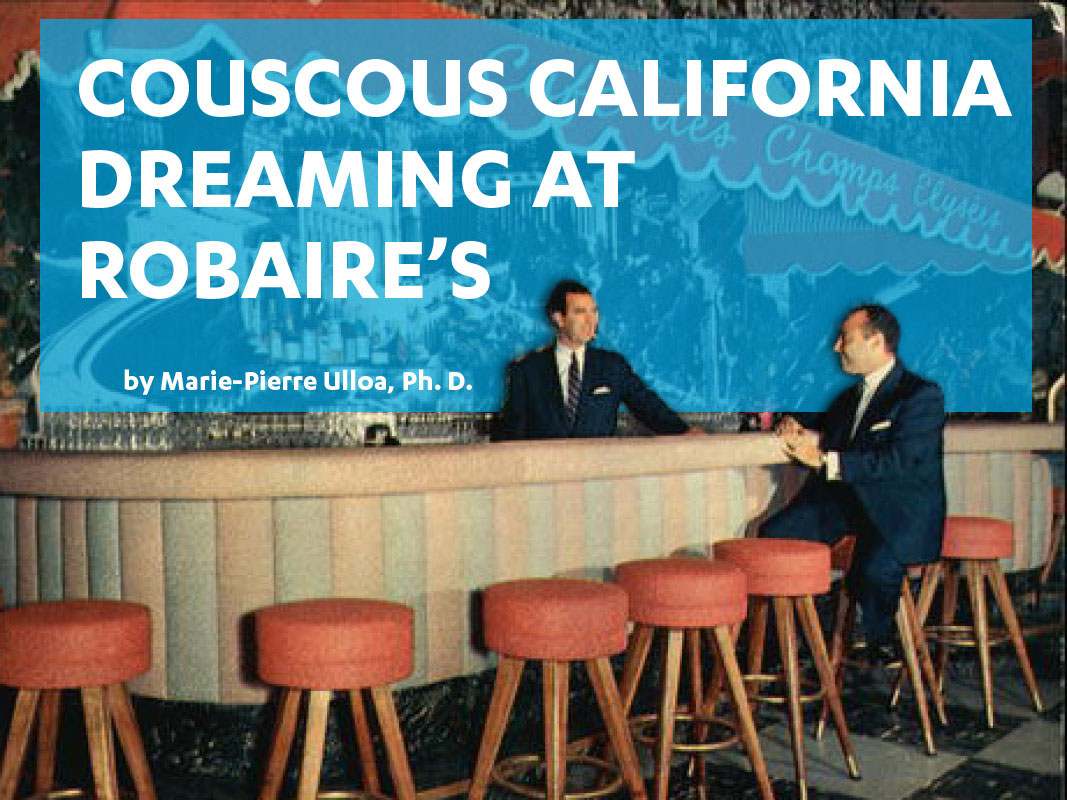

While Koutoubia makes its Moroccan flavors an explicit part of its marketing, an earlier generation of North African Jewish restaurateurs like Robert Robaire introduced Maghrebi dishes to California by promoting their French-ness. At Robaire’s, traditional French dishes like escargots, bouillabaisse, and cassoulet–Louis Armstrong’s favorite at Robaire’s–were served in a stereotypical French décor, complete with accordion music and white tablecloths and napkins, which impressed patrons at the time. Their navigation of Los Angeles’ culinary scene mirrors their triangular negotiations of their identities between the territory of origin (Tunisia), the imaginary territory of the ex-colonizer (France), and the host territory (California). Through French food, Tunisian Jewish immigrants slowly cultivated a taste for couscous among generations of Angelenos, establishing a place for themselves in the culinary and cultural fabric of the city and the state.

Citation MLA: Ulloa, Marie-Pierre. “Couscous California Dreaming at Robaire’s.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/couscous-california-dreaming/

Citation Chicago: Ulloa, Marie-Pierre. “Couscous California Dreaming at Robaire’s.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/couscous-california-dreaming/.

About the Author:

Marie-Pierre Ulloa is a Lecturer in the French and Italian Departments at Stanford University… More

Citations and Additional Resources

This short essay is based on Ulloa’s book Le Nouveau Rêve Américain: du Maghreb à la Californie [From North Africa to California: The New American Dream]. Paris: CNRS editions, 2019.

1 The pieds-noirs are the French and European settlers who came to Algeria after the 1830 French conquest to occupy the land, and the Harkis are the native Muslim Algerians who were soldiers in the French army during the Algerian War of independence (1954-1962). The Harkis were considered traitors or collaborators by the Algerians of the independence movements.

2 Another restaurant, owned by a Moroccan Jew, has played a similar, albeit later, role: Koutoubia in Westwood. It opened its doors in 1978 whereas Robaire’s opened in 1952 (discussed below).

3 Patt Morrison, “La Revolution in L.A.: The Fractioned French Community Has Finally Found Something It Can Agree On: It’ Time To Celebrate!” Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1989, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-07-14-vw-3843-story.html.

4 Russ Parsons, “The French and their Food: L.A. Says Reluctant Au Revoir to Robaire’s,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 15, 1990, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-10-25-fo-4374-story.html.

5 Gérard Uzan later became Robert’s business partner and opened his own French restaurant, Maison Gérard, in 1963.

6 Maurice Bismuth (Tunis, 1891-Los Angeles, 1965) was a member of the “École de Tunis”.

7 Another “Mauresque” reference is the most famous literary one of the female character in Camus’s classic The Stranger. She is the catalyst device of the unfolding of the plot.

8 William Bracken, “Robaire set the Couscous standard,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 19, 2005.

9 On the homepage of the Koutoubia website, it is noted that “Koutoubia was established by Moroccan immigrant Michel Ohayon in 1978. With recipes handed down through his Mother and family, Koutoubia quickly gained the reputation as one of the best Moroccan restaurants in the country with Chefs, Food Critics and Diners alike.”

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.