During the first few decades of the twentieth century, Los Angeles and its Southern California environs were growing and expanding beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. The 1920s saw nearly 100,000 new arrivals in the city each year, tripling its population by the end of the decade. The opening of the Panama Canal, lowered costs of railroad travel, feats of agricultural and water engineering, the development of the San Pedro-Long Beach deepwater port, and the popularization of Hollywood films all gave ample fodder for the city’s boosters to extol the wonders of sunny Southern California.1

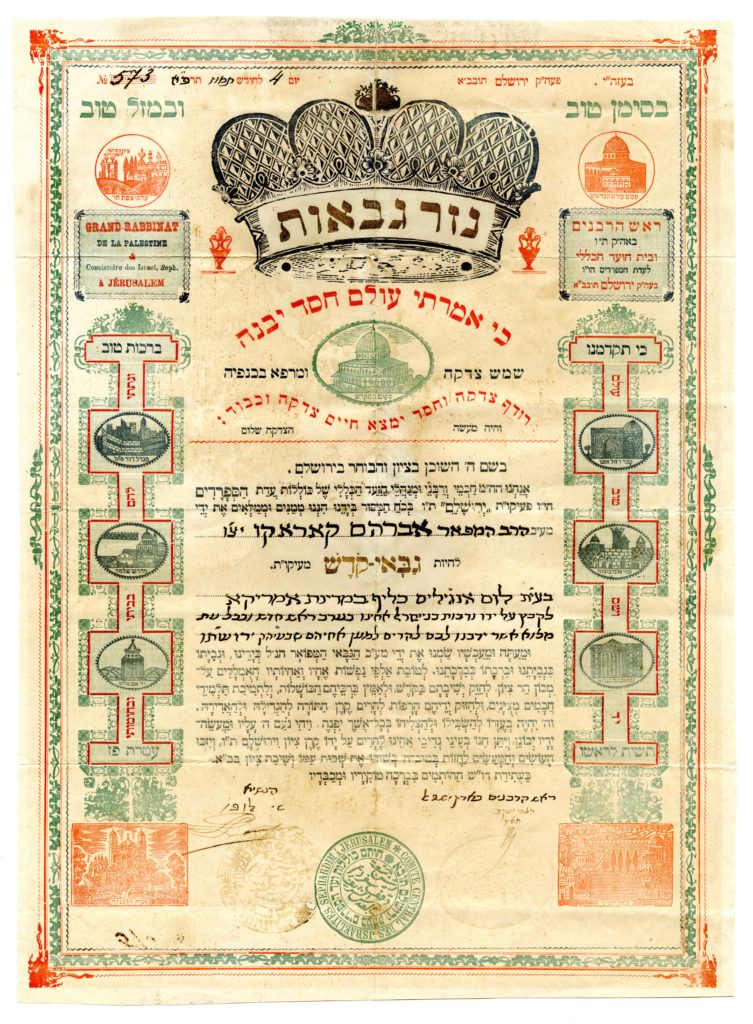

And while most of the newcomers to the city were white, American-born Protestants from the East Coast or Midwest, the region was home to sizable immigrant populations, especially Mexicans, but also Japanese, Russians, and, of course, Jews. An elite class of German Jews, like the Hellman and Newmark families, had already established a Jewish presence in the city since its earliest days under American control, and since the turn of the century, Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe (often via the US East Coast) soon dominated Jewish L.A. Meanwhile, a small handful of Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire began arriving in L.A. in the first decade of the twentieth century, settling in the downtown area like most of the city’s other immigrant arrivals. Young, single men barely speaking English like Jacques Caraco came to L.A. after having participated in the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, an event which brought many Ottoman Sephardim to the U.S. for the first time.2 Those who would end up in Los Angeles also included Raphael and Maurice Amado, and as well as Mordecai “Papa” Zitoun, Chief Manager of the Jerusalem Exhibition at the Fair. While extended families would soon become the backbone of Sephardic communal life in L.A., the early years witnessed the formation of mutual aid associations – landsmanschaftn, as they were known among Yiddish-speakers – based on common origin and designed to provide basic religious ritual and burial services. Ahavat Shalom was the first of its kind, formed in 1912 under the religious leadership of Jacques Caraco’s father, Rabbi Abraham Caraco.

Early twentieth century Sephardic immigrants, particularly the more ambitious among them, certainly shared a web of connections. Rabbi Caraco, before arriving in L.A., worked at a cigarette factory in New York City owned by the Schinasi Brothers. Morris (also known as Moise or Musa) Schinasi grew his tobacco enterprise from modest beginnings as a cigarette roller in Alexandria, Egypt that he later plied at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. His brother Solomon would later join him in New York City and make millions on Americans’ growing taste for Turkish-style tobacco, which the Schinasis imported from abroad, particularly Greece. Solomon’s son Leon had his own successes with the Standard Commercial Tobacco Company, which counted Raphael and Maurice Amado on the executive board. While the Schinasi brothers never lived in Los Angeles, their patronage and connection to other immigrant Sephardic Jews helped shape the contours of Sephardic Los Angeles in unexpected ways.

As they adjusted to life in the growing urban sprawl of Los Angeles, Sephardic immigrants made do by peddling fruits and vegetables and running shoe-shine stands on the streets of a busy downtown – before automobiles took over completely. Before these immigrant peddlers and their native-born children became businessmen with their own storefronts, and before their downtown residences – often boarding houses – were abandoned for the ubiquitous Southern California dream of home-ownership, Sephardic L.A. was assuredly urban, male, and unorganized. This development took place as more Sephardim – from Ottoman lands via New York City, Seattle, or Latin America – made their way to booming Los Angeles. Reuniting with their compatriots, friends, children, spouses, brothers, sisters, and cousins, Ahavat Shalom could no longer accommodate the clashing personalities and the compromise of ritual customs needed for a cohesive community. The estimated 160 Sephardim in L.A. in 1915 would grow exponentially over the next decade, and new organizations would emerge to match their needs. Jews from the island of Rhodes split off to form Sosiedad Paz i Progreso in 1917, while 1920 witnessed the creation of the Comunidad Sefaradi de Los Angeles and the Haim vaHessed group. Membership being restricted to adult men, L.A.’s Sephardic women would form semi-independent organizations – sisterhoods and auxiliaries – alongside each of the three groups mentioned. Paz i Progreso’s Ladies Auxiliary was established around 1919, the Comunidad’s Sisterhood in 1924, and Haim vaHessed’s women’s group soon after.

Like other immigrant communities – and the earliest Anglo settlers in California – the first Sephardim were young, single men. In 1920, only about a third of Sephardim were women, as opposed to about half a decade later. Throughout the decade, the average age remained around 24 years. Other statistics between 1920 and 1930 show a marked change in L.A.’s Sephardim. By 1920, three-quarters of Sephardim were foreign-born and in 1930 a little over half were. Although Los Angeles was still largely a White, Protestant city at this time, Sephardim shared the common denominator of being migrants to the city.

Meeting in rented theater halls or the rooms of other Jewish communal buildings in and around downtown, the geography of Sephardic L.A. of the 1910s and 1920s reflected the map of its members’ workplaces and residences. However, the dissolution of downtown L.A’.s residential character combined with the upward mobility of the community led Sephardim out of the relatively crowded surroundings of downtown and into the newly developed single-unit family dwellings of “suburban” Los Angeles. By 1930, most of L.A.’s Sephardim – many having arrived within the previous several years – settled in South Los Angeles near Exposition Park in their own homes. In contrast, L.A.’s Ashkenazi population began to move eastward from downtown into Boyle Heights, as well as westward into the Hollywood and Fairfax area.3

In many ways, Sephardim in this period followed a similar pattern to Ashkenazim, and one that also calls to mind the migratory patterns described by historian Becky Nicolaides in her study on the city’s South Gate community. As white, upwardly middle-class homeowners, and a public identity transitioning from the workplace to the local community, Sephardim in South L.A. and the WASPs of South Gate shared enough in common to guarantee the former a secure place in the city’s promise of suburban comfort.4 Yet Sephardim differed in many key ways. Ethnic and religious ties bound this community in more significant ways than it had for their neighbors, and the local identity was more attuned to other Sephardim in the area – what Aron Hasson had termed the L.A. judería, using the Spanish term for Jewish neighborhood.5 Unlike the judería of medieval Spain or the more modern Jewish urban ghettos, Sephardim of L.A. never made up a majority – nor even a significant percentage – of the neighborhood’s residents. And yet, for many of them, the area was, for all intents and purposes, a Sephardic neighborhood, where families, friends, and los muestros (Ladino for “our own”) lived closely together, often in the same buildings. If the community was outwardly similar to other white Americans, internally – especially retrospectively – Sephardic communal life was close-knit, familiar, and neighborly.

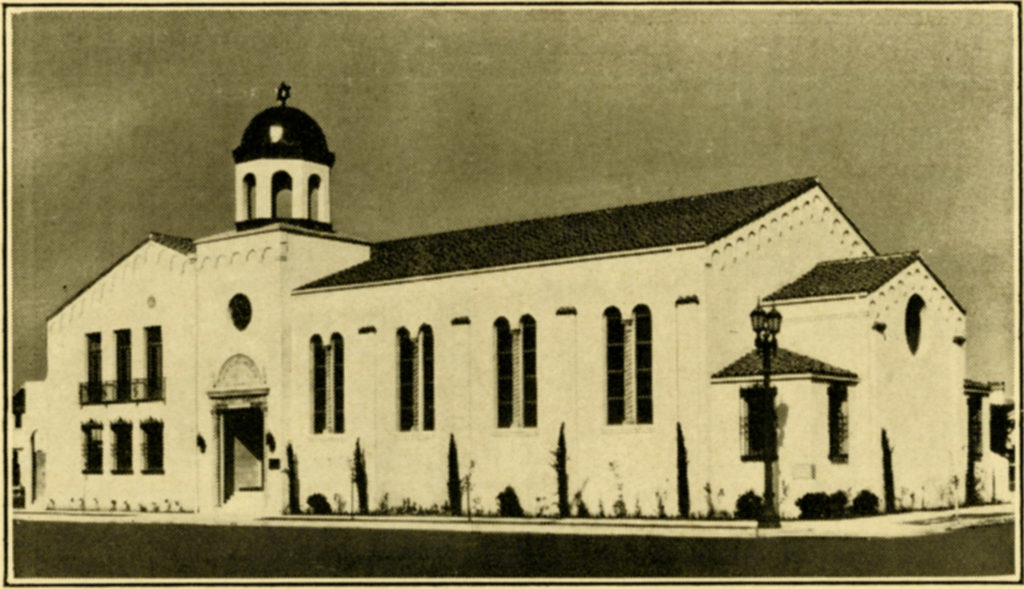

Through the 1920s, Sephardic economic and communal life was centralized in downtown, still strong as the city’s economic and political base despite the sprawl. Soon enough, institutional growth and expansion followed the residential shifts of that decade. Faced with a growing and moving membership and evidenced by the economic successes of individual Sephardim, both the needs and the means of purchasing land and erecting a synagogue structure were in place for all three of the major Sephardic organizations by 1930. Haim vaHessed, also known as the Sephardic Brotherhood, managed to erect the first building, Temple Israel, around 1926 on Vernon Avenue in Leimert Park. Within the next eight years, the Comunidad would build Temple Tifereth Israel on Santa Barbara Avenue (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue) in 1932 and Paz i Progreso – which would soon change its name to the Sephardic Hebrew Center – built their Temple Ohel Avraham at 55th St. and Hoover Street in 1934. These three institutions, in a way, triangulate the geography of Sephardic communal life at this time and point to the firm planting of these families and institutions in Los Angeles for decades to come.

The latter two synagogues were built during the Depression, and these large building projects couldn’t rely on local financial support given the limited means of their congregations’ memberships. Rather, Maurice Amado, the uncle of local Sephardic leaders Richard and Milton Amado, would donate a substantial amount from his New York-based tobacco industry fortunes to help build TTI (and would donate again several decades later to fund their next move to Westwood). The estate of Istanbul-born and Shanghai-based rickshaw, rubber, and leather tycoon Abraham Cohen would provide significant financial support for the construction of the Sephardic Hebrew Center synagogue on Hoover Street. Cohen, who died in 1934, left behind several children and a widow – Linda (nee Haim) Cohen – who would remarry Jack Notrica, a founding member and leader of the Sephardic community. It was ultimately Linda who oversaw the liquidation of her deceased husband’s Chinese assets and continued to contribute much to the community, not only financially but also as an involved and active member. The forging and reforging of national and transnational family networks, whether across an ocean or a continent, proved essential for the literal building of Sephardic life in Los Angeles. The linkage of family, community, and the temple seem to have mutually reinforced one another.

Alongside the centrality of family life, which for L.A.’s Sephardim could ostensibly include the entire community as nearly everyone seems to have been related in some way, the synagogue was critical in maintaining a sense of “Sephardicness.” Less concerned with religion and spirituality per se, the leaders of the synagogues – the executive boards – saved their praises for the insurance of Sephardic customs, pride, identity, and continuity. Rabbis and cantors were approved for their appropriateness to Sephardic ritual, and cultural and social events were prized for their “oriental music,” belly dancing, and the delicious borekas and boyos. Indeed, Rabbi Jacob Ott of Temple Tifereth Israel said as such many years later in 1987, remarking that in America, “the Sephardic Jew has only the home and the synagogue.”6

For both the family and synagogue, the Sephardic woman played a key, if often under-acknowledged role. As mentioned above, the Ladies’ Auxiliaries and Sisterhoods were semi-independent from the exclusively male executive boards of the temples, collaborating on many events and fundraising but by and large maintaining their own activity and internal functionings. Officially affiliating with the Sephardic Community in 1949, over twenty years after its founding by Rebecca Hattem, the Sephardic Sisterhood would remit raised funds to the Community and jointly run the Talmud Torah, as well as often preparing traditional Sephardic food for social events. In their newly acquired middle-class environment, the Sephardic family no longer required women (or children) to work as much as they or their immigrant mothers had to a generation earlier. With this “free time,” volunteerism became a hallmark activity of the middle-class woman, especially with regard to fundraising, children’s education, and cooking.

Residentially, occupationally, and institutionally, Sephardic L.A. by the 1930s had, for the most part, exhibited most of the characteristics of white, middle-class Los Angeles. Twenty-five years after the first few arrivals of Sephardim in the city, a veritable community existed with a multitude of organizations, the hard days of survival passing into days of expansion.

Citation MLA: Daniel, Max Modiano. “Breaking Ground in the 1930s.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/breaking-ground-in-the-1930s/.

Citation Chicago: Daniel, Max Modiano. “Breaking Ground in the 1930s.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/breaking-ground-in-the-1930s/.

About the Author:

Max Modiano Daniel is a doctoral candidate in the History Department at UCLA… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Kevin Starr, Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

2 Albert J. Amateau, “Sephardim in the Worlds Fair,” as appears in Aviva Ben-Ur, Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 29.

3 Max Vorspan and Lloyd P. Gartner, History of the Jews of Los Angeles (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, 1970).

4 Becky Nicolaides, My Blue Heaven : Life and Politics in the Working-Class Suburbs of Los Angeles, 1920-1965 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

5 Aron Hasson, “The Sephardic Jews of Rhodes in Los Angeles,” Western States Jewish History Quarterly, 6, no. 4 (1974).

6 As quoted in The Jewish Calendar, vol. 5, no. 1, March 1987.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.