“What actually makes a recipe or dish Sephardic? Is it a style of cooking? Does it only refer to dishes I ate as a child that my nona brought from Turkey? Can it include dishes that I, being Sephardic, cook and bake? Does it mean a certain way of presenting, stuffing, or cooking? Does it refer to spice or flavoring? And what is Sephardic food going forward? Does Sephardic food include dishes that were brought to the United States and have undergone generations of adaptation through using local produce and ingredients? Does it include Israeli dishes, and does it include the cuisine that can be made kosher from countries like Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, and other Mediterranean countries? I think the answer is yes to all.” – Linda Capeloto Sendowski1

For its preparers and (many) of its eaters in America and Los Angeles, the scents and tastes of Sephardic food like borekas or biscochos bring to mind nona’s kitchen and a sense of family, home, and community. The nona, a common Ladino term for grandmother, was the cornerstone of many Sephardi families in twentieth century Los Angeles and the font of knowledge and expertise not only on food but of homemade remedies for illnesses and handicrafts like textiles. A common Ladino expression captures the praise often given to these women’s culinary and cultural labor: bendichas manos (blessed hands). By examining their bendichas manos—taking it seriously as cultural work done for the family and broader community, rather than simply as a quaint part of women’s domestic duties—we can get a glimpse into the intimate and evocative memories and relationships that Sephardim have embodied through their foods. Food helps recover the central place that women had in defining the image of American Sephardi culture over time.

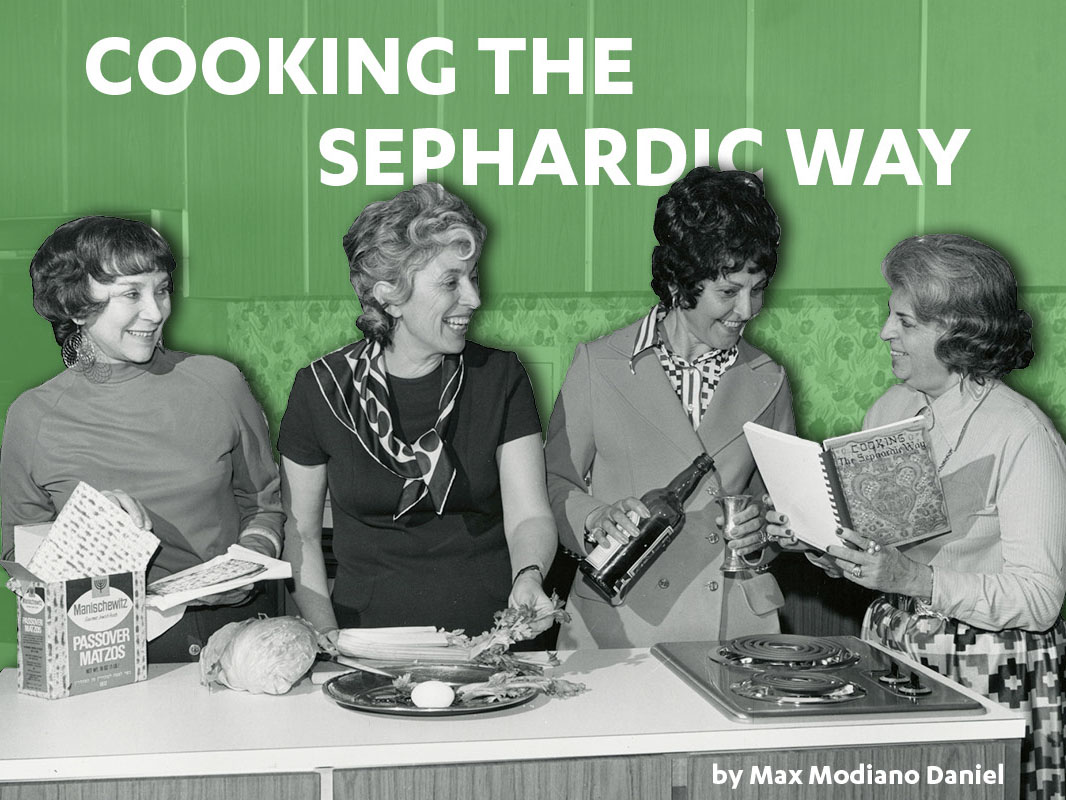

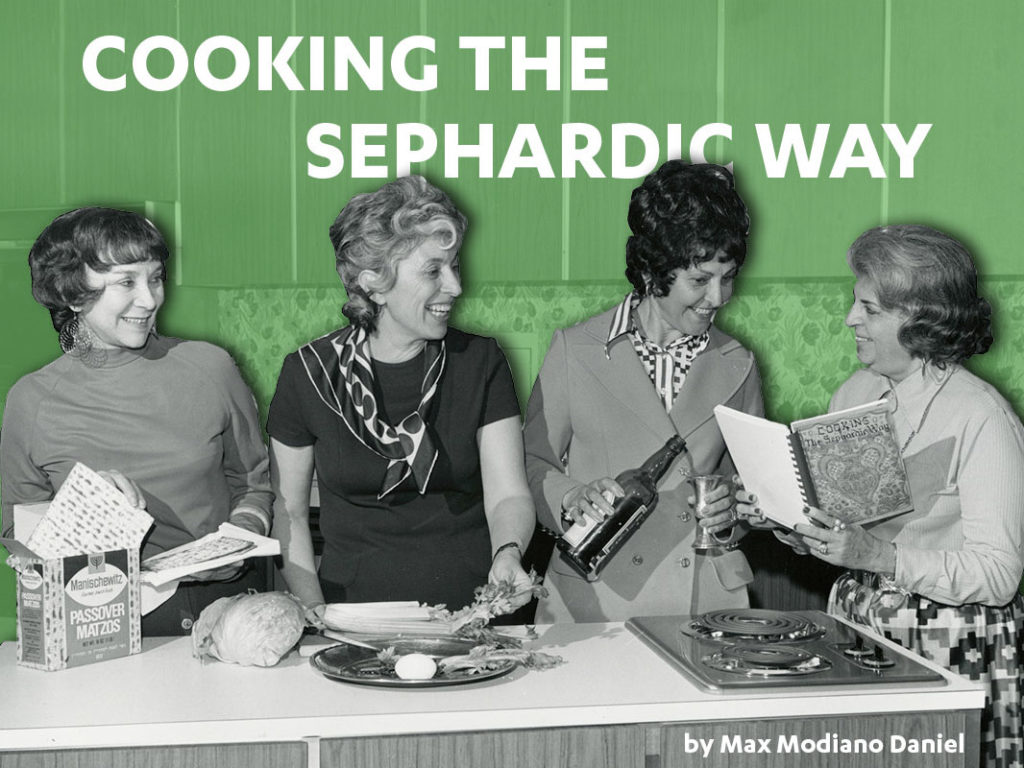

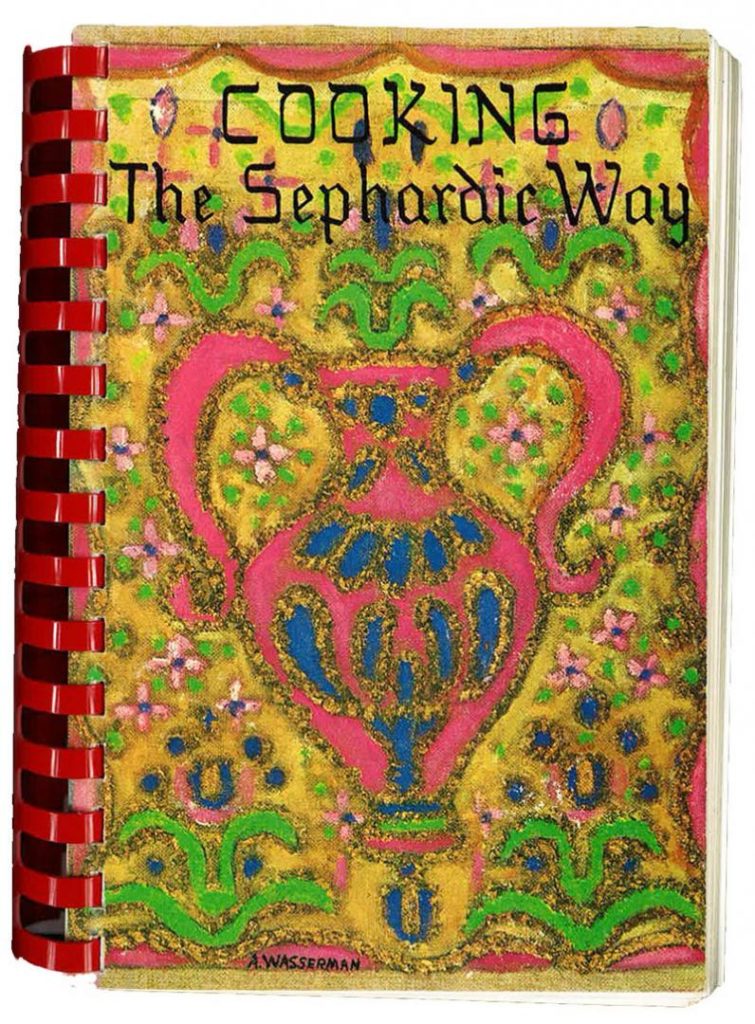

This essay examines one particular form of that cultural work: the Sephardic Temple’s Sisterhood cookbooks. Originally published in 1971 under the title Cooking the Sephardic Way, a “sequel” of sorts was published in 2016 as the Sephardic Heritage Cookbook. The two volumes provide historical bookends to a period of rapid transformation in the Sephardic community: from its Balkan-Levantine base of Judeo-Spanish-speaking immigrants who arrived beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century, Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel grew to include women from North Africa, Iraq, Iran, and elsewhere, a broadening geographic diversity that, along with language, could most acutely be measured through their food traditions. More practical changes, like ingredient availability and cooking technologies in America, influenced some of the ways these inherited recipes were prepared in the late twentieth century. As both communal fundraisers and reservoirs of cultural memory, the two cookbooks provide a tasty entrée into the intimate spaces of Sephardic family kitchens, the ever-changing meanings of “Sephardic” food and a history of Sephardic Los Angeles in which the experiences of women are brought to the fore.

Cooking the Sephardic Way

According to one account, the idea of creating a Sephardic community cookbook in L.A. emerged as early as the 1940s, due to the prompting of Ashkenazi Jews wanting to learn to cook Sephardic foods. Yet it was only in a community bulletin in 1965 that the Sephardic Sisterhood put out a call for recipe submissions. In the call, Reggie Arditti outlined one of the cookbook’s goals as being “to make available for all, recipes for a distinctive type of cookery that finds a wide acceptance wherever it is tried.”2 As the foreign-born generation gradually acculturated to American society and the native-born grew up embedded within it, it was no longer obvious that Sephardic culture was exclusively for Sephardic Jews. The cookbook’s audience was also laid out by the community’s (Ashkenazi) rabbi, Jacob Ott, who noted that it was geared toward both “the American born generation Sephardi” and the “non-Sephardi who conceives of Sephardic food as exotic and unique.” By making Sephardic food and culture appealing to outsiders, they hoped the cookbook would provide a “much needed source of funds for our sisterhood’s many activities.” Evidently, it worked: Cooking the Sephardic Way was an “enormous financial success,” going through ten printings in just as many years.

Financial support was not, however, the cookbook’s primary goal: as Arditti described, the cookbook aimed “to perpetuate in written form recipes that might otherwise be lost in years to come.”3 As editor Pearl Roseman described, transmission and survival of cultural memory was central to their efforts: “Sephardic cookery is passed from mother to daughter and taught by the look and feel of the dish rather than by written recipes,” stressing that the role of the matriarch was so important that “if you moved away from your mother, you were out of luck” in making any of the typical Sephardic foods featured in the cookbook.4 Roseman, née Elias, was born in Los Angeles to a family that was very active in Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel: her maternal grandfather, Abraham Caraco, was the community’s first rabbi in the 1920s. But it was the loss of the intangible Sephardic culture that came from her mother that motivated her and her colleagues to create the cookbook. As she described in an interview after its release, a “culture’s cookery can become just as extinct as plants and animals if the recipes are never written down.”5

The connection between recipes and the women who prepared them was such that after family members had passed away, food could evoke remarkably strong memories and emotions of mothers and grandmothers. “Some people have said that they sat down and cried when they read some of the recipes and little stories that go with them,” cookbook co-editor Reggie Arditti answered when asked about the feedback from Cooking the Sephardic Way. “Seeing their names [of mother and grandmothers] and the towns they came from brought back emotional feelings,” Arditti continued, noting how merely the text of the cookbook–not even the food–could spark such a deep reaction.6 Memories of the kitchen abound among the children of Sephardic immigrants: Elaine Lindheim notes that while her family was “very Americanized in most ways, if you were to visit my mother’s kitchen, you would know we were a Sephardic family. It is the memories from this kitchen that I treasure most.” Similarly, Kaye Hasson Israel recalls her childhood among the Rhodeslis of Los Angeles and locates the kitchen as a place where she tells her children and grandchildren “the stories I learned about Rhodes and about our family’s life in Seattle and then Los Angeles.” These two American-born Sephardic women understand food as both part of and distinct from their American settings and locate the kitchen and female relatives as where the “old country” and the “new country” interact most memorably.7

Sephardic food is also deeply rooted in what it means to be a Sephardic woman. According to Lil Benveniste, the way that her mother “instilled…[a sense] of being a Sephardic woman, mother, and housewife, [was] through food.”8 In traditional Sephardi homes in Ottoman lands, married women–and marriage was the goal—were primarily housekeepers and stewards for their families. Young women were taught not only food preparation and the concomitant laws of kashrut but also sewing and childrearing skills. Furthermore, we see the connection of femininity and food preparation through the stories and descriptions attached to the recipes in Cooking the Sephardic Way, many of which are connected to the life-cycle events of Sephardic women. Roscas or rolls are prepared for the Sephardic bride-to-be after she goes through the banyo (mikveh or ritual bath) ceremony, and the sharope blanko dessert is made for bridal festivities. Other recipes relate to some of the traditional customs and roles of Sephardic women. Mothers would spell out the name of her children in cinnamon on a dish of sutlach (rice pudding), the eldest daughter should have the honor of carrying the dulse (sweets) tray to visiting guests, and the mina de espinaka (spinach pie) was typically “served for brunch when the menfolk returned from Passover services.”9 Not only was food the means to feed a family, but it was also deeply tied into the religious and social roles of women in Sephardic life.

Art Benveniste, “Sephardic Women from Rhodes demonstrate their culture,” ca. 1980s Los Angeles. Women in the video include: Rosa Franco, Rebecca Amato Levy, and Amelie Cohen, among others.

The 1971 Cooking the Sephardic Way does acknowledge some American influence, noting that “American cooking nowadays [takes] advantage of ‘convenience foods and equipment.’” One example, perhaps indicative of where these changes came from, mentions that in preparing borekas, a “resourceful, modern Ashkenazi daughter-in-law experimented with frozen spinach.”10 But more often, traditional Sephardic foods were resistant to the new, American setting. In the home video above, recorded by Art Benveniste around 1982 in Los Angeles, for example, a group of Judeo-Spanish-speaking women—some of them contributors to the 1971 cookbook—gave a cooking demonstration adamantly claiming that they never bought readymade products from the store, asserting the authenticity of their teachniques. Unprompted, one of the women, Rebecca Levy, acknowledges that her Turkish coffee is “not life Mr. Coffee,” and later, when describing the best way to prepare the dough for borekas, exclaims in her Ladino-tinged accent that “they don’t know in America boiling water.” For them, American products and cooking methods are not up to par for these special foods. The resistance put up by America also appeared elsewhere, in a different guise, when Kaye Israel recalled how “young people used to ask their elders not to prepare the old-style foods [because they] thought the food was too different…we wanted things we thought were more American.”11

And yet despite those changing culinary preferences – or more likely because of them – the members of the Sephardic Sisterhood intervened to guarantee the recipes’ survival. Cooking the Sephardic Way became just the third Sephardic cookbook published in the United States and still occupies a place of pride in many Sephardic kitchens in L.A. and beyond.12 The associations mentioned in 1971 persisted decades later and showed that many women still held onto their roles as guardians of Sephardic culinary heritage. Though the cookbooks never sought to replace familial transmission, they clearly understood that these collections were serving to perpetuate a heritage that was in danger of extinction.

The Sephardic Heritage Cookbook

The “sequel” to Cooking the Sephardic Way, 2016’s Sephardic Heritage Cookbook, is rich with detail and stories about how a new generation of Sephardic women connects food with their pasts. The preface notes that because of the changing makeup of the local Sephardic community, the original cookbook “no longer reflect[s] the Temple Sisterhood that authored it” since the “membership has expanded to include families from Iran, Morocco, Egypt, Israel, and the Caribbean.”13 The contributors bring their “own story and recipes to weave into the rich Sephardic tapestry” and provide biographical vignettes about their family and traditions that aim to bring the recipes and the food into larger cultural and personal contexts more representative of Sephardic community in the twenty-first century.

Unlike the 1971 publication, the Sephardic Heritage Cookbook qualifies some of the geographical locations attributed to the recipe authors and illustrates the changing landscape of Sephardic Los Angeles. Almost all the recipes that come from Balkan, Turkish, Greek, or Rhodesli backgrounds are given by the children or grandchildren of immigrants. By 2016, there were far fewer Jewish women born in the Judeo-Spanish heartland to provide recipes than there were forty years earlier. On the other hand, Moroccan, Egyptian, and Persian recipes typically came from women born abroad. Nevertheless, each subgroup—the second or third generation stemming from Ottoman lands and the immigrant women who arrived post-World War II or post-Iranian Revolution—offers stories relating food, recipes, family, and the past.

Many women describe an idyllic, simpler, life growing up in the “old country.” Alfreda Yazdi, Neda Mehdizadeh, and Dalia Melamed recall life in Iran as relatively comfortable, at least until the 1978 revolution when the women experienced the struggle of living in Khomeini’s Iran and the pain of migration to the United States. Like most of the biographical tales attached to Sephardic recipes, they are warm, positive, childhood tales—yet also a little mournful. They wax nostalgic about an irretrievable past that happened in another place, invoking departed relatives, and refer to the present as a site of struggle for transmitting these recipes and traditions to the next generation.

Especially in Los Angeles, the survival of Persian foodways is relatively assured, if the numerous markets and restaurants—Jewish-owned or not—are any indication. Those like Dalia Melamed write about the easy availability of special ingredients for Persian food today as compared to when she first arrived in the U.S., and Neda Mehdizadeh notes that “Persian Jews lost many material things on their journey to the United States, but they…continued their fabulous culinary heritage.”14 The most perishable of goods also turns out to be the most resilient.

Like in 1971, the sisterhood’s Cookbook Club spelled out their desire to “transmit to their children and grandchildren the special tastes they remember from their family kitchens.” In some senses, this “sequel” is proof that the 1971 sisterhood’s aims had been achieved. Elaine Lindheim’s recipes acknowledge that although she never knew her immigrant grandparents, she “inherited a love of Sephardic culture and cuisine” from them.15 The connection between food, family, and transmission is so strong that even relatives that one never met could provide the fuel for cultural and culinary transmission.

Reyna Simnegar is one of dozens of young, Sephardic women who offer recipes and cooking demonstrations on YouTube. Born in Venezuela to a non-Jewish family with converso roots, she met her Persian Jewish husband while attending UCLA and learned many of her recipes from her mother-in-law, which she has compiled into her own cookbook, Persian Food from the Non-Persian Bride. In this video, she instructs viewers on how to make gondi, popularly known as “Persian Matzah balls.” The Sephardic Heritage Cookbook contains two recipes for gondi.

Whether or not the women of 2016’s Sephardic Heritage Cookbook are representative enough to mark the success of cultural and culinary transmission over the past several decades, they still express ambivalent attitudes about their ability to do the same for their own children. Kaye Israel is very conscious about this process and utilizes twenty-first century means to ensure the survival of her Sephardic culinary heritage. For Israel, documenting and transmitting food is a communal, family affair—her daughter, Marcia Weingarten, “blogs her recipes and videos so [her] nieces and nephews and their children and grandchildren…can learn and keep the tradition alive.” In this way,” she concludes, “our legacy continues.”16 That legacy, it seems, is no longer exclusive to women nor only through oral or written transmission—her nephews can now watch a video online to learn to make borekas. Nevertheless, not everyone is as optimistic. Alexandria-born Mirelle Mathalon “strives to maintain her Egyptian culinary traditions,” but she doubts “whether the next generation here in America will pick up the culinary reins.”17

If food is a major touchstone of Sephardi culture in America, and the immigrant’s kitchen is its home, then the Sephardi mother and nona are its stewards, representatives, interpreters, and promoters. Certainly not all Sephardi women took on this role, nor were men totally absent. But the authors of these two cookbooks understood the central, connective, and sustaining role of food—and of the bendichas manos that prepare it—in their maintenance, perpetuation, and evolution of Sephardi family and communal life in Los Angeles and beyond.

Citation MLA: Daniel, Max Modiano. “Cooking the Sephardic Way.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/cooking-the-sephardic-way/.

Citation Chicago: Daniel, Max Modiano. “Cooking the Sephardic Way.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/cooking-the-sephardic-way/.

About the Author:

Max Modiano Daniel is a doctoral candidate in the UCLA History Department… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Linda Capeloto Sendowski, Sephardic Baking from Nona and More Favorites: A Collection of Recipes for Baking Desayuno and More (Beverly Hills, CA: Self-published, 2015), 41.

2 The Sephardic Jewish Community and Brotherhood of Los Angeles. Temple Tifereth Israel Bulletin, February 1965.

3 Ibid.

4 Barbara Hansen, “Sephardic Customs, Cuisine, History,” Los Angeles Times, Sept. 9, 1971. Roseman was later editor of the highly successful California Kosher in 1991.

5 Ibid.

6 Stephen Stern, The Sephardic Jewish Community of Los Angeles (New York: Arno Press, 1980), 284.

7 Lindheim and Israel’s comments appear in Sephardic Heritage Cookbook: Ottoman, Persian, Moroccan, Egyptian Recipes and More (Los Angeles: Sephardic Temple Or Chadash Sisterhood, 2016), 20 and 28 respectively.

8 In Stern, The Sephardic Jewish Community of Los Angeles, 278.

9 Cooking the Sephardic Way, 132.

10 Ibid., 16.

11 Ana Maria Gabriel, “Joe Benon Has Sabor,” Los Angeles Times, February 20, 2002.

12 Previous publications include: 1958’s Kosher Syrian Cooking by Grace Hasson and 1968’s Sephardic Cooking by the Ladies Auxiliary of Sephardic Bikur Holim in Seattle, Washington.

13 Sephardic Heritage Cookbook, 3.

14 Dalie Berookhim Melamed and Neda Khazai Mehdizadeh, in Sephardic Heritage Cookbook, 108, 156.

15 Sephardic Heritage Cookbook, 7.

16 Sephardic Heritage Cookbook, 28. The blog can be found at bendichasmanos.com.

17 Sephardic Heritage Cookbook, 90.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.