by Rachel Smith

At backyard parties, beach picnics, and trips to Catalina Island, Sephardic Jews in Los Angeles gathered outside to eat and drink, talk news and play cards, and celebrate engagements, birthdays, and holidays. These were opportunities to relax in the sun, but this busy social calendar was also central to Sephardic communal life. It helped new immigrants who settled in Los Angeles to maintain strong bonds and a network of support in a vast and unfamiliar city.

The growth of the Sephardic community in Los Angeles in the early twentieth century coincided with the emergence of new forms of leisure and recreation across the United States. For many years, recreation and leisure had been restricted privileges that explicitly marked wealth and social status. At elite social clubs, lavish hotels, and expensive restaurants, wealthy white sophisticates enjoyed the finest of American high culture, their tastes catered to by large staffs composed primarily of people of color. Exclusivity was part of the appeal; by enforcing racial segregation and other barriers to entry, leisure culture reinforced unequal relations of race, class, and power.

But after the turn of the century, American leisure culture began to open up to previously excluded groups, including Jews. The sunny skies and temperate climate of Southern California placed it at the forefront of this change. Ardently promoted as a region of health and recreation, Southern California offered a wide range of recreational activities that were outdoors—and so often more affordable—making them available to a growing population of consumers. With the democratizing of leisure, Sephardic Jews took advantage of these new forms of outdoor recreation and consumption, marking their status as upwardly mobile Americans.

Many Sephardic Jews who emigrated to the United States had arrived with little money and knowledge of English. In the 1910s, most Jews from Rhodes, for example, worked shining shoes or selling flowers and produce on downtown street corners. After saving enough money, some opened small shops or stands and purchased new suburban homes. In the 1940s, as their children expanded their businesses or attended colleges and entered the professions, the Sephardic community enjoyed a general prosperity that enabled them to enter into this new American leisure society.

This economic and physical mobility was contingent on Sephardic Jews’ ability to transgress racial boundaries. While Los Angeles never had the type of racially discriminatory segregation laws that prevailed in the Jim Crow South, most of the city’s residential neighborhoods were governed by restrictive racial covenants. These clauses, which were written into mortgage agreements and prevented property owners from renting or selling to non-white minorities, lasted until the late 1940s, when the Supreme Court declared such practices to be unconstitutional. Sephardic Jewish racial designation was amorphous and malleable, allowing them to join the upwardly mobility and settle in white neighborhoods. With the door open to home ownership and college education, many left downtown and moved westward into new suburban homes. Thousands of Jewish soldiers who served in World War II and the Korean War took advantage of the benefits afforded them by the GI Bill and embraced middle-class life in the suburbs.

Backyard Gatherings

Homeownership was central to the vision of good living in Southern California. Although suburbs had historically been home to only the wealthy, a new mass suburbia presented homeownership as an achievement that was attainable for all. Instead of living in small downtown apartments, middle-class families could live in suburban bungalows, surrounded by front and back yards. The bungalow became the archetypal home of middle-class suburbia. Intended for a single family, it stood separate from other houses, with its own plot of land. Open to the outdoors, its connotations of relaxation and recreation made it the ideal home for this envisioned leisure culture of southern California.

During the City Beautiful movement in the late nineteenth century, nature was posited as the antidote to the ills of urbanism and industry, and urban planners built parks and green spaces to bring nature into the city. But Southern California took the opposite approach; there, the city itself was brought into nature and the country. Instead of adopting a City Beautiful plan or buying undeveloped land for recreational spaces, Los Angeles spread out housing and allocated land for private yards. Suburban residences surrounded by gardens and palm trees, with backyards and barbeques, patios and swimming pools were popularized in southern California.

As Sephardic Jews increasingly moved westward out of the city and into suburban bungalows, front and back yards became important social spaces. Home movies taken in the 1940s and 1950s capture on film backyard barbecues, birthday parties, and engagement parties. Throughout these films, party-goers smile and wave at the camera, an exciting new addition that had recently become more compact, portable, and affordable, bringing home movies within reach of the middle class.

Backyard Video – 1950s home movie of Hasson, Benoun & other families from Aron Hasson.

During these parties, friends and family caught up, circulated news, and played cards and backgammon. In the Ottoman world, smoking, playing cards, and games of backgammon were common forms of leisure, especially as means of breaking the Sabbath. Sephardic Jews brought these customs with them when they settled in the United States.

Communal Picnics

In a city that notoriously prioritized private space over public space, outdoor recreation was one thing that people in Los Angeles did both publicly and collectively. While the city preserved little land for parks within the city, the beaches provided ample recreational space. Large groups of Sephardic Jews, often numbering over 100 people, gathered annually for seaside picnics in Palisades Park, Santa Monica, Redondo Beach, and Seal Beach. These popular communal picnics were often organized by Sephardic synagogues and youth groups.

For many Sephardic Jews, these picnics and trips to the beach reminded them of their lives before immigrating to America. Rebecca Amato Levy grew up on the island of Rhodes and recalled the small beach in the Jewish quarter where she spent the Sabbath and summer days. She also recalled that, as a child, she and her friends dressed up for class picnics in the park. The sunny skies and temperate climate that they encountered in Los Angeles reinforced this memory of the Mediterranean.

Picnic – L.A., Santa Monica of Tarica, Hasson, Benveniste, Benoun families from Aron Hasson.

Sephardic Jews continued to gather annually for community picnics throughout the twentieth century. The Sephardic Hebrew Center organized an annual picnic for decades, and some families, growing larger with each generation, began organizing their own family picnics. Today, some circles of friends carry on the tradition of getting together at beaches throughout Los Angeles, meeting for a meal or a game of cards.

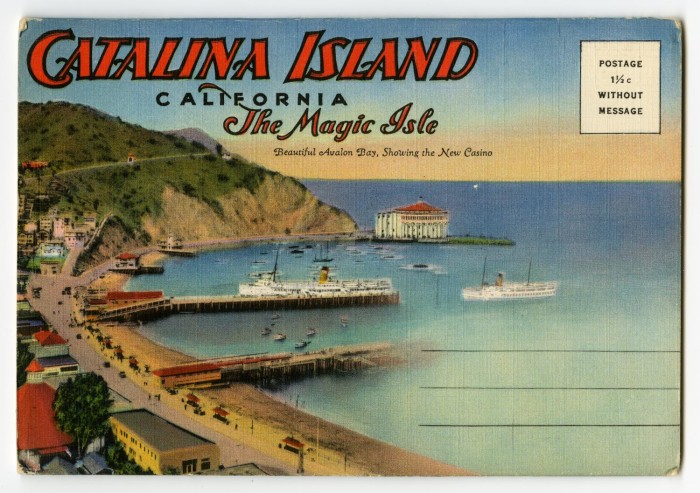

Catalina Island

About twenty miles off the coast of Los Angeles, Santa Catalina Island was promoted as a relaxed and scenic island getaway with a healthy and balmy climate in contrast to the dense and insalubrious American city. For decades, Catalina drew large crowds of visitors to its shores, competing with other top tourist destinations across the country. The draws of nature and outdoor recreation reflected Southern California’s promise of health and rejuvenation.

This privately owned island began as a resort island catering to primarily to wealthy southern Californians. Its inaccessibility was an asset for those who wanted to leave the crowded beaches of Los Angeles behind and had the time and money to do so. But after its purchase in 1919 by William Wrigley of bubblegum fame, Catalina transformed from a regional resort into a national destination. With his immense wealth and business savvy, Wrigley reoriented the island towards the middle class, opening it up to a much wider public. By the 1920s, Catalina was receiving over 400,000 visitors, twice the number of Yellowstone National Park. It remained impervious to the Great Depression, reaching 700,000 visitors during the 1930s. Wrigley transformed Catalina into a preeminent destination for Los Angeles residents and tourists alike.

Sephardic Jews joined the steady stream of visitors drawn to Catalina’s shores, vacationing there every summer for decades. Their experience enacted the values of middle-class American leisure culture, but it was also particular to them as Sephardic Jews. Rhodesli Jews returned to Catalina annually because they found it strikingly reminiscent of Rhodes. It had similar vegetation, ocean vistas, and a faint view of the California coast line comparable to the view of Turkey from Rhodes. Avalon, the seaside town in Catalina, had a similar town square and fountain, and a waterfront promenade like the Mandraki in Rhodes, where Jews, Greeks, Turks, and Italians strolled along the harbor, sat at outside cafés, and listened to the bands performing. Rebecca Amato Levy expressed this sentiment, remarking that, “I can’t tell you the emotions we have coming here on vacation. So many things remind us of the island of Rhodes here in Catalina.”

Summer vacations in Catalina were so popular among Sephardic Jews that traditional Sephardic foods were served at parties in the beach towns and they could not walk down the street without seeing people they knew. Together they swam at the beach, went for drives, played games of poker, and danced at the night club. For many, the annual summer pilgrimage to Catalina was a sort of symbolic return to their island; it evoked the memory of Rhodes while creating new memories in a new country.

1948 Catalina of Hasson, Benveniste & Benoun families from Aron Hasson.

For Sephardic Jews in Los Angeles, these backyard barbecues, seaside picnics, and trips to Catalina reflected their identity as both American and Sephardic. The upward mobility and westward migration that Sephardic Jews experienced in the early twentieth century resulted from their ability to transgress racial boundaries and dovetailed with the opening up of a new outdoor leisure society. Their middle-class status afforded them new forms of consumption, and they joined Americans across the country in buying homes in the suburbs and vacations to Catalina.

Yet for many, these experiences were also particular expressions of their Sephardic identity. Socializing outdoors in the sun and temperate climate reminded them of life in the Mediterranean. Surrounded by friends and family, they spoke Ladino, ate traditional foods, created and maintained communal bonds, and found spouses. During these gatherings, they brought and adapted their traditions to Los Angeles, and took advantage of the new opportunities that its democratizing leisure culture offered them as they merged their Sephardic traditions with and American norms and moved out and up.

Citation MLA: Smith, Rachel. “Sephardic Jews and the Democratization of Leisure.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/democratization-of-leisure/.

Citation Chicago: Smith, Rachel. “Sephardic Jews and the Democratization of Leisure.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/democratization-of-leisure/.

About the Author:

Rachel Smith is a graduate student in History at UCLA… More

Citations and Additional Resources

Culver, Lawrence. The Frontier of Leisure: Southern California and the Shaping of Modern America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Hasson, Aron. “The Sephardic Jews of Rhodes in Los Angeles.” Western States Jewish Historical Quarterly 6, no. 4 (1974): 241–54.

Moore, Deborah Dash. To the Golden Cities : Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A. Toronto: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1994.

Shachar, Nathan. The Lost Worlds of Rhodes: Greeks, Italians, Jews and Turks between Tradition and Modernity. Portland: Sussex Academic, 2013.

“Social Calendar – 1967.” The Sephardic Star. The Sephardic Hebrew Center. 1967.

Viens, Gregori, Hespèrion XX (Musical group), and National Center for Jewish Film. Island of Roses: the Jews of Rhodes in Los Angeles. Waltham, Mass.: [The National Center for Jewish Film, distributor], 2006.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.