In the late 1950s, two young Spanish professors at UCLA, Samuel G. Armistead and Joseph H. Silverman, began recording a huge trove of Judeo-Spanish romansos among Sephardim in Los Angeles and Seattle.1 One of their subjects was Esther Varsano. A decade later, I was to encounter Versano’s voice while a graduate student at UC Berkeley, taking a course in medieval literature in which we were examining the fourteenth and fifteenth century romancero, or Spanish ballad tradition. One day, the professor walked into class and put a cassette recorder on the table. Without a word, he pressed Play and we heard the crackly voice of an elderly woman, singing a romance—in a language I instantly identified as Ladino. Our professor had brought the tape to demonstrate how ballads live in oral tradition. He went on to explain that the Sephardi Jews had preserved Spanish romancos (as ballads are called in Ladino) for 500 years in the diaspora. My nona spoke Ladino, of course, but I had never heard her sing, let alone these songs. Then and there I knew that this would become the topic of my doctoral dissertation and my field of specialization. I would retrace their steps in those same cities, recording a few of the same singers but many new ones as well. My field collection became the book, Romances sefardíes de Oriente: Nueva recolección (Eastern Sephardic Ballads: New Collection), published in Spain in 1979.2

Why did the romansos and other lore survive so long in the diaspora? What did they mean to the people that sang them today? I sought to answer these underlying questions in my study. I argued that the Judeo-Spanish romanso survived not because of some idealistic nostalgia for Spain—this is a romantic notion generally expressed by Spanish intellectuals and academics since the late nineteenth century. Closer socio-historical examination revealed that the survival of the Judeo-Spanish language and cultural traditions had more to do with the social and cultural autonomy enjoyed by minority communities in the Ottoman Empire. This millet system permitted Sephardi communities to maintain their own institutions and thrive, and with that preserve linguistic and cultural practices brought from the Iberian Peninsula.

If these songs were not a nostalgic harkening back to Spain, then what did they mean to the people who sang and transmitted them through the generations? With time and distance from their Peninsular origins, ballads began taking on new significations. Royal or historical tragedies transformed into family misfortunes. Kings and queens into mothers and fathers. Christian symbolism often morphed into Judaic affirmation. However, not surprisingly, dramatic stories of incest and murder survived intact. With the breakup of the Ottoman Empire into nation states and the twentieth-century Sephardi diaspora, people were transported to a new life in the Americas and community coherence began to wane. In this context, I maintain that Sephardi cultural traditions in Los Angeles become a way of holding onto at the memory of a collective and familial Sephardi past. To the generation that I recorded, the ballads conjured their own childhoods in Turkey and Rhodes, and a deep remembrance of their nonas and nonos, parents, and communities.

What is a romanso?

What distinguishes the romanso from other Sephardic songs? In the first place, the romanso must tell a dramatic story. It must have a plot, characters, a beginning, a conflict, and a resolution. Like all ballads, they typically recount dramas of love, trickery, war, death, separation and return, adultery, incest, and other typical folkloric themes. Most recorded Sephardic songs are actually not ballads, but rather kantikas, traditional songs for weddings, songs celebrating childbirth, lullabies, and love songs whose lyrics are fixed. Because it is passed down orally, the romance/romanso is subject to greater variation. Parts of the story can drop out, forgotten; a long story can become shortened; or two different stories can be stitched together. Sometimes only fragments remain in peoples’ memories. Collecting romansos, one encounters different versions of the same story, brief fragments as well as longer narratives, depending on the singer’s memory. However, every snippet is meaningful and can contribute to the larger picture of that ballad across geography and time.

If the lyrics of the romance in oral tradition can vary, the form cannot. The Spanish romance has a set poetic form. It is comprised of an open number of verses to tell the story. Each verse has sixteen syllables, divided into two eight-syllable parts, or hemistichs. Each verse rhymes at the end, but the rhyme is assonant rather than consonant, so the vowels in the stressed syllables make up the rhyme scheme. For example, in the following verses of El cautivo del renegado (The Captive of the Renegade) the rhyme is comprised by the accented vowels é-a:

Me cativaron los moros entre la mar i la arena

me kitaron a venderme en Xerez a la Frontera

Many of the ballads that were transmitted in the Sephardi communities come from fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in Spain, when the romance became popularized. In Spain, they might be sung in marketplaces by juglares/itinerant bards, or during work, social gatherings, or at home, and passed on through oral tradition all the way down to our times. With the advent of the printing press in the fifteenth century, romances were reproduced on broadsheets with lovely woodcuts, sold in public markets, or bound into chapbooks that wealthy collectors would purchase. Thanks to them, we have priceless fifteenth and sixteenth century collections to compare with modern oral tradition, and see how the romance travelled across the Spanish-speaking world.

In studying each ballad in detail, comparing it to versions that had been collected from oral tradition in Spain, two key dimensions emerged: (1) the Sephardi ballads were often more archaic than the peninsular versions, preserving versions from before expulsion; (2) as distance and time set in, the original sources and meanings of the ballads often changed and creative new ballads emerged, speaking to the resilience of the form and tradition.

Kualo topí? What did I find?

Inspired by the work of my mentors, I set out in late 1972 on a quest throughout Los Angeles for romansos. Where does one start in such a vast metropolis, where the community is physically so dispersed? My mother set me on my course, suggesting I speak with Mrs. Emily Sene. She had met at the Senes’ famous Sephardic summer picnics in Redondo Beach. Every month the Senes also held gatherings on Wednesday in Ladera Park, near Inglewood. Isaac played his oud with and a small band of musicians. To a background of Turkish music, men and women would play cards, sing, gossip, and bring food. There I would meet and record many singers or visit them later in their homes.

The Senes were my inroad into the turkinos, those who came from Istanbul (Constantinople), Smyrna, and various towns along the Sea of Marmara (Tekirdag, Milas, Çanakkale, Gallipoli). Mrs. Rebecca Levy and Dr. Irving Benveniste connected me to the Rhodeslis, those who came from the island of Rhodes, although some of the Rhodeslis also went to the Ladera Park Wednesdays. And of course, each singer would also refer me to another one, so in that way, I crisscrossed L.A., following the trail with my trusty Sony cassette recorder. In every home I was offered the traditional spoonful of dulse with a glass of water, followed by borekas, bulemas, sfongatiko/kuajado de spinaka, boyikos, biskochikos, pastel, cafe turko, and so on. Needless to say, fieldwork was a culinary delight!

The first woman I contacted was referred to me by Mrs. Sene. Susana Levy and her husband lived in Bell, deep in Los Angeles. On November 18, 1972, they received me warmly, with Sephardic delicacies, as would everyone I visited. The Levys had arrived in Los Angeles just ten years earlier, from Cuba. Born in Istanbul, Mrs. Levy had lived from the age of thirteen in Havana. There, she married and started a family, only to uproot once more with the Jewish exodus to the United States in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution. Mrs. Levy gifted me with my first recordings of romansos, perched on the arm of her sofa, nostalgically entoning the songs she learned from her mother. I will never forget the shiver that went through me as she began, “Avía un rey de Francia, Glicia / tres hijas i el teniya,” (“There once was a king of France, Gaul / who had three daughters”), in perfect romance form. The ballad of Delgadina was my very first recorded romanso, crossing centuries of space and time, from medieval Spain to the Ottoman Empire, Havana, and now, to Los Angeles. The wonder of the oral tradition!

Delgadina, one of the most popular romances throughout the Hispanic world, is about resisting incest, about a king who imprisons his daughter in a tower because she won’t submit to his “attentions.” He orders that she be given rancid orange juice and spoiled meat to eat. She begs her mother and sisters, and eventually her father himself to give her water. When her father finally agrees to give her water, Delgadina has given her soul to God. The Sephardic renditions of this ballad are different from the traditional Spanish versions, in which the violation of a social taboo is punished by the intervention of God. Here, however, the daughter’s strength of will, preferring to give her soul to God than to submit, becomes the father’s punishment. In this way, the Sephardic versions turn a drama about kings and queens into an intimate, family tale and moral lesson that celebrates human will and dignity rather than divine intervention.

One of my favorite sessions was with three sisters, Rachel Bega, Regina Hanan, and Violet Benveniste, who grew up on the island of Rhodes. They delighted in singing songs learned in childhood. The sisters spoke Ladino at a rapid clip, interrupting each other, bursting into laughter, and having a grand time remembering the songs their mother used to sing. They laughed that their “signature” romanso was “Tres ermanikas eran” (“There once were three sisters”) and began to sing.

“Tres ermanikas eran” is derived from the Greek legend of Hero and Leander, in which a father incarcerates his daughter Hero in a tower in the middle of the sea (fathers, daughter and towers seem to be popular tropes in balladry!). Her lover, Leander, swims out to her, guided by the light of the tower but drowns in the storm-tossed sea. In the Sephardic versions, instead of drowning in the sea, the lover reaches the tower and is pulled up by Hero’s braids (a nod to Rapunzel) to have his hands and feet washed and enjoy a sumptuous dinner! Here is where the sisters’ version stops, as they had forgotten the ending. But even in their truncated version, the “contamination” is evident. The ending for the Sephardic Hero and Leander was borrowed from an entirely different ballad, turning the tragic legend into a story of love fulfilled.

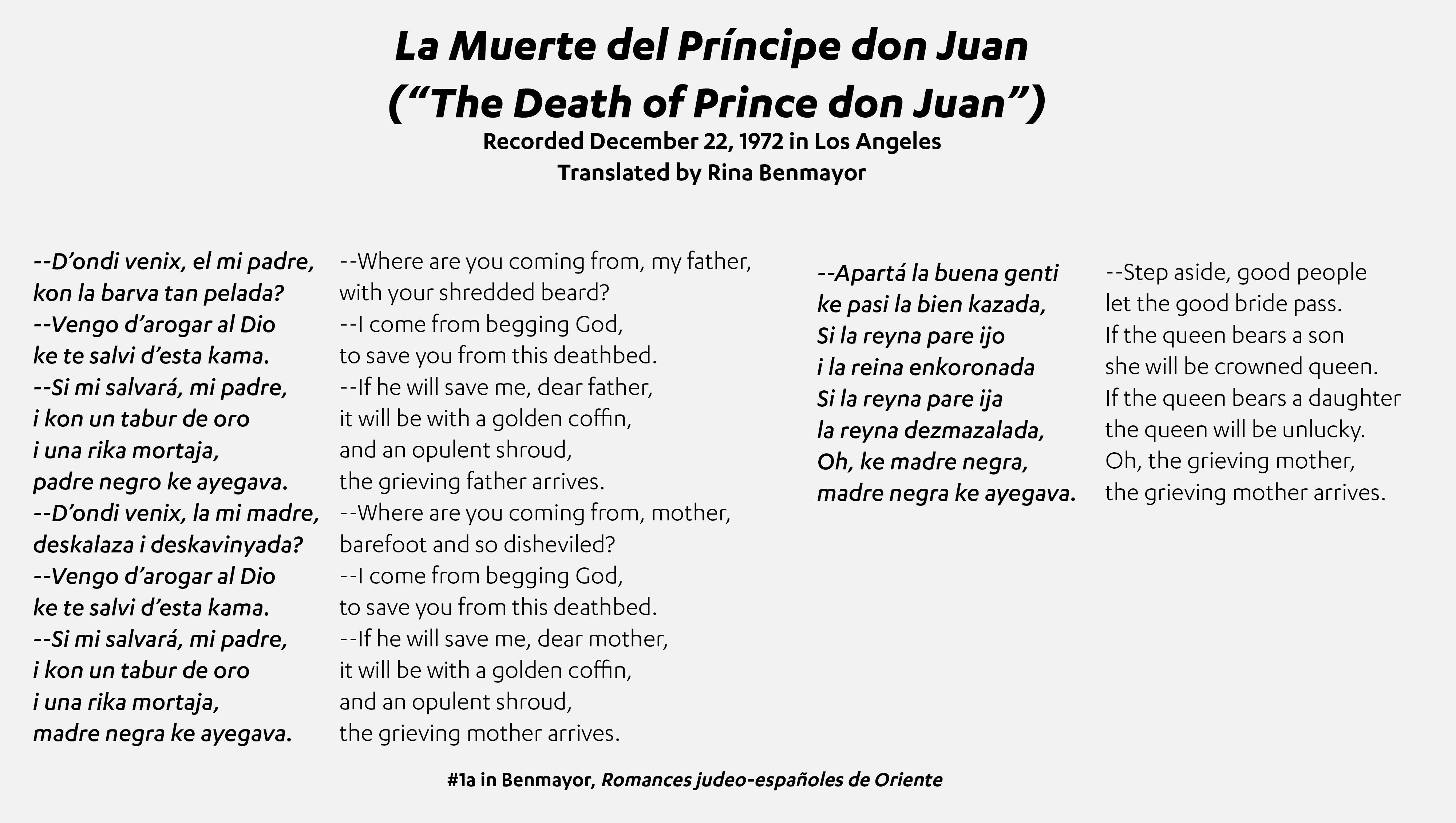

Romansos about historical events in medieval Spain are also part of the Sephardi repertoire. La muerte del príncipe don Juan (The Death of Prince don Juan) is one such example. Sung by Mrs. Sarah Hasson, from Smyrna, it recounts the death of the only son of Queen Isabel and King Fernando, who signed the edict that expelled the Jews from Spain. Don Juan dies in 1497, after the expulsion, and yet the ballad is preserved in the diaspora. The Eastern Sephardi versions retain archaic details about the event, but they also make the ballad relevant to its singers. This romanso was sung as a dirge, a funeral song to commemorate the tragic death not of a prince but of a son.

The final stanza belongs to another funeral ballad “David llora a Absalom” (David Mourns Absalom), and became attached to the Príncipe don Juan story to emphasize the dramatic nature of this royal story. At the same time, the romanso reflects the male-centeredness of Sephardi culture, with preference given to the son and male heir.

These adaptations help us understand the creative power of the Judeo-Spanish romancero. They offer a window into how oral tradition evolves—through preservation, recreation, creative mixings, and most importantly, shifting of messages to express contemporary Sephardic moral codes and worldviews. Over the next few months, I would go on to record sixteen Angelino romanso singers from Turkey and Rhodes, singing long, shortened, and fragmented versions of 34 of the 39 ballads in my collection. My romanso singers included:

- David Ben Susen (Tekirdağ); Susana Levy, Tamar Perez (Istanbul)

- Victoria Caraco, Sarah Hasson (Smyrna)

- Caden Soustiel Telias (Milas)

- Bohor Yohai (Gallipoli)

- Rachel Bega, Regina Hanan, Violet Benveniste, Fasana Cohen, Leonora Halfon, Rebecca Levy, Estrella Mayo, Selma Mizrahi, Amelia Notrica (Rhodes)

Along with the romansos, I recorded a wealth of other lore from many more people. In my collection are kantikas (modern love songs with fixed lyrics wedding songs, lullabies, religious songs), refranes (folk sayings), konsejikas de Johá (trickster stories), and folk cures. These remain to be catalogued and studied.

Although people lived dispersed throughout the city, they maintained a semblance of community coherence. Family ties, picnics and park gatherings, synagogue events were all occasions for cultural transmission—food, language, music. However, the next generations would gradually lose Ladino and no longer hear or pass on the old Spanish romansos. They might still know some of the love songs, wedding songs, and music for other occasions today, through performances of groups like Kantigas Muestras, or commercial recordings.

But in the 1970s, Los Angeles was still a goldmine of traditions brought from the old country. With each recording visit, I was overcome by exhilaration and wonderment at hearing a romanso come alive right before my eyes. It was both an imagined and a concrete bodily memory—of forbearers carrying these songs across geographies of space and time, of times and places where I had never been, and yet in some way, I had. I was incredibly mazaloza as each singer gifted me with their treasures. They brought their romansos and rikordos with them to a new continent and a new city, making them our legacy to preserve.

Citation MLA: Benmayor, Rina. “Judeo-Spanish Romansos in Los Angeles.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/judeo-spanish-romansos/

Citation Chicago: Benmayor, Rina. “Judeo-Spanish Romansos in Los Angeles.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/judeo-spanish-romansos/.

About the Author:

Dr. Rina Benmayor is Professor Emerita of Literature, Oral History, and Latinx Studies, in the School of Humanities and Communication at CalState Monterey Bay… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Armistead was a medievalist and folklorist and Silverman a Spanish Golden Age scholar. Both also had gifted voices and on command could sing the ballads they avidly collected, reproducing the melismatic style of Turkish musical improvisation to perfection. Together with ethnomusicologist, Israel J. Katz, they would publish more than ten volumes and dozens of articles on Sephardic ballads from around the world. Today, their signature opus, the three-volume collection The Folk Literature of the Sephardic Jews, can also be accessed online, where one can hear the songs.

2 Originally published by Gredos Press, the book is now out of print, but copies of the book are available at university libraries. The entire collection of my recordings is now housed at the University of Washington Libraries, and the Seattle portion of the collection has been digitized and is available online. The Los Angeles portion of the collection has yet to be archived and catalogued.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.