by Julia Phillips Cohen, Ph.D.

Like so many immigrants before and after them, Ottoman Jews who made the trek halfway across the globe to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century faced a number of challenges, ranging from financial hardships and perilous journeys to the unraveling of social and familial networks. Whatever their reasons for leaving, they also inevitably had to ask themselves: to what extent did leaving the empire require them to forsake that which made them Ottoman? Respondents answered this question in a number of ways. Some, such as Moshe Gadol—an avowed Zionist who had immigrated to the U.S. from Bulgaria and served as editor of an influential Judeo-Spanish periodical entitled La Amerika—suggested that his Ottoman coreligionists in America no longer owed their allegiance to their erstwhile home. Their loyalty belonged to the country in which they now resided, Gadol argued. (He was both skeptical about the sincerity of the Ottoman state’s recent declarations of equal rights for Ottoman non-Muslims and concerned that Ottoman Jews would remain foreigners on American shores unless they actively rejected their Ottoman citizenship).

Others begged to differ. Among them was an Ottoman Jewish man based in Venice, California who identified himself only as “Ben Leon” in a letter he sent to Gadol’s journal, La Amerika, in the summer of 1912. Ben Leon wrote his appeal with a sense of urgency, he explained, because he feared that the thousands of his coreligionists who had begun entering the U.S. from the Ottoman Empire in recent years were trying to Americanize too quickly without considering the consequences. His principal concern was whether these Jewish émigrés should naturalize as U.S. citizens. Ben Leon thought not, both for pragmatic and sentimental reasons. On the practical level, he argued, doing so might hinder Ottoman Jews’ ability to return to their country of origin and enjoy the rights they would have been guaranteed there as Ottoman citizens. Yet he also suggested that abandoning their Ottoman citizenship represented a show of ingratitude toward the empire, which had given shelter to the Jewish exiles from Spain so many centuries before and which continued to house their descendants at the time of his writing.

The question of whether to remain Ottoman or eschew that identification reverberated beyond the legal realm. It also affected the choices people made about what they wore, ate, drank, smoked, and how they used their leisure time. In recounting their journeys to the United States in the early twentieth century, Ottoman Jewish immigrants frequently describe removing their fezzes or−more dramatically still−hurling them into the sea as soon as they got on a boat departing from Ottoman waters.1 Their stories suggest that leaving the empire required them to abandon the physical trappings of their Ottoman past. Yet, things were rarely so simple. Ottoman immigrants clearly continued to identify themselves with things Ottoman well after making their transatlantic journey. Across the United States, Ottomans of different backgrounds frequented “Oriental” cafes that served Turkish coffee and other tastes of home both as a way of feeding their nostalgia for the lands they had left and forging new social, political, and business networks. At times, such initiatives employed overtly political language and symbols, including those of the Ottoman Muslim restaurateur and the Ottoman Jewish cobblers who printed the crescent and star of the Ottoman flag on their advertisements. Jewish entrepreneurs in early twentieth-century New York even named their newly created brand of Turkish coffee after the Ottoman sultan of their day.2

This marketing of a wide range of products as Ottoman fit into a broader pattern. Some of the earliest Jews to arrive in the U.S. from the Ottoman Empire came as purveyors of “Oriental” goods. Alongside their Armenian, Greek Orthodox, and Muslim Ottoman compatriots, such individuals sought to seize on a growing interest in Turkish tobacco, “Oriental” carpets, and other items from the Islamic “East” that swept Europe and the U.S. during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.3 Many arrived and then settled abroad in the wake of the various international and regional fairs held across the United States and Europe during the period. In the American context, these included the Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876, the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, the 1894 California Midwinter International Exposition in San Francisco, the Pan-American Exposition held in Buffalo, New York in 1901, and the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, which opened its doors in St. Louis in 1904. Continued identification with or rejection of one’s imperial heritage was thus influenced by legal, political, communal, and business considerations alike.

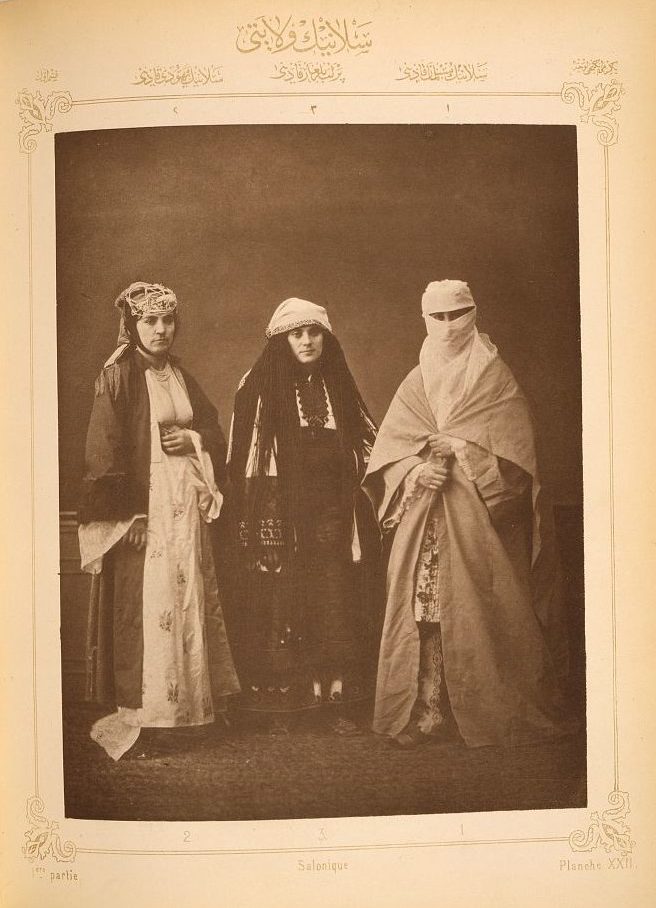

Contrary to the impression given by the 1912 debate that took place in the pages of La Amerika between the Ottoman Jewish writer from Venice, California and Moshe Gadol, the question was often not whether to continue to identify as Ottoman but rather when, where, and how to do so. This was precisely the approach that the socialist Judeo-Spanish newspaper La Bos del Pueblo of New York took in the spring of 1919 when it called on its readers to attend an upcoming “Oriental ball” while dressed in the traditional kofyas, robes (entaris) and other traditional outfits of their Ottoman forebears. Whoever drafted the advertisement clearly assumed that the paper’s readers would still have had access to such items, even if they no longer wore them in their daily lives: perhaps they had squirreled them away in their closets or preserved them as part of their trousseaux. No doubt in many cases, such outfits were family heirlooms that relatives had worn or carried with them across the Atlantic.

In other cases, Ottoman Jewish immigrants and their descendants turned to the marketplace in search of their heritage, buying elaborate Oriental carpets from U.S. dealers to form part of a child’s dowry or purchasing the specialized implements needed to make Turkish coffee in order to preserve family traditions.

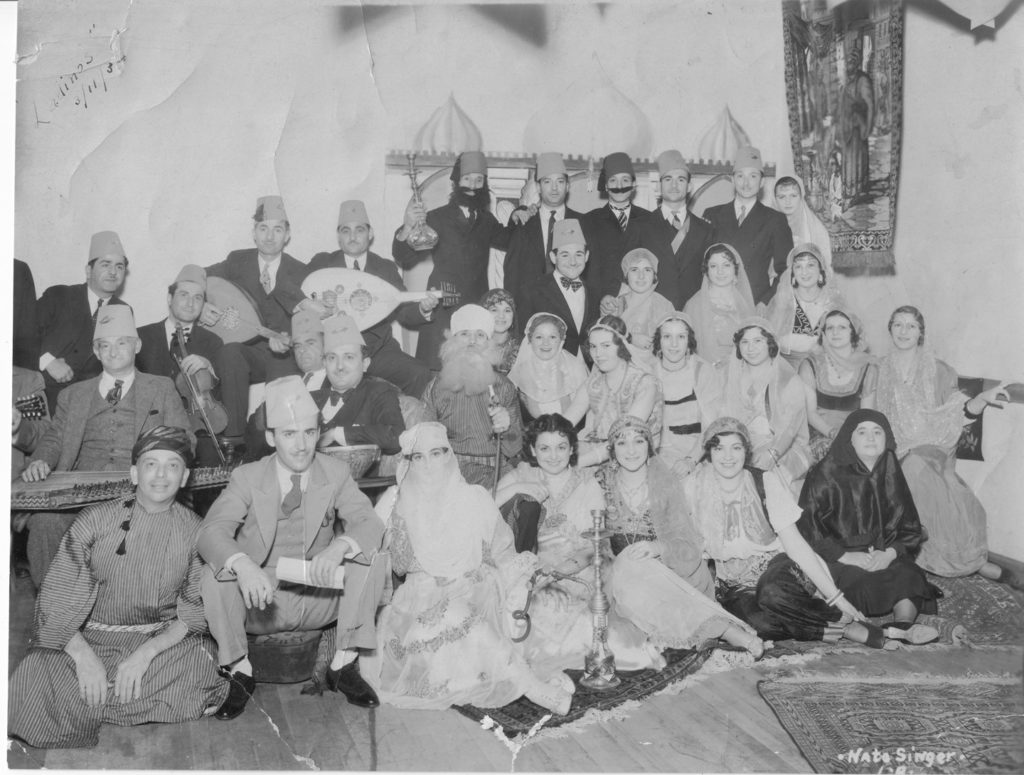

It appears that a blend of these two trends influenced a practice that grew up among members of the Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel in Los Angeles by the 1930s. In the spring of 1934, a group calling itself the “Ladinos” came together to celebrate a “Turkish Night”—a tradition that ended up continuing, and evolving, among different Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Jewish constituencies in Los Angeles throughout the rest of the twentieth century. The evening was meant to offer congregation members entertainment while also serving as a fundraiser for the synagogue: notes preserved in Temple Tifereth Israel’s archive from the moment mention that a “small fee of 35 cents was charged” for entrance, while a later report from the temple’s bulletin, El Shofar, suggested that the event had succeeded in raising substantial funds.4

The image of this Turkish Night held by formerly Ottoman Jews and their descendants in Los Angeles in 1934 is particularly illuminating for what it suggests about community members’ evolving relationship with their Ottoman past. The group captured on camera in that year was dressed in a wide array of styles: most of the men in the picture wore tailored suits with fezzes, yet others donned baggy trousers and robes for the occasion. The women, for their part, wore headscarves and transparent veils paired either with dresses or baggy pants. Despite the diversity in their forms of dress, they were all clearly meant to signal an association with the Ottoman Empire.

Like the Sephardic socialists who attended an “Oriental ball” in New York a decade and a half earlier, the “Ladinos” of mid-1930s Los Angeles had chosen to wear clothing that they identified with their Ottoman heritage. But unlike the outfits that La Bos del Pueblo had encouraged its readers to wear in 1919—such as the kofya, which famously formed part of the traditional dress of married Jewish women from Ottoman Salonica—the clothing featured in this “Turkish Night” in Los Angeles had little that marked it as specifically Jewish. The tailored suit and fez was itself a relatively new style promoted by the early nineteenth-century Sultan Mahmud II as a kind of equalizing uniform for Ottoman men regardless of religion: such outfits could just have easily been those of Ottoman Muslim or Christian men. In the case of the women who chose to cover their faces or heads—whether with gauzy veils or a thick black çarşaf pinned under the chin—dressing in forms most commonly associated with the styles of late Ottoman Muslim women offered yet another way of celebrating their imperial heritage.5

As they performed their relationship to their lands of origin, the celebrants of this and similar festivities engaged in practices shaped by their lives in their new homes. These included parades, costumed dances, and exhibits held by members of other recent immigrant communities in the United States during the period.6 The Oriental balls and Turkish Nights that Ottoman Jews and their descendants put on in early twentieth-century New York and Los Angeles were not merely the inventions of diasporic nostalgia, however. They were also well rooted in patterns that Jews had already developed back in the empire during the late nineteenth century. Indeed, already by the 1890s, Jews in Istanbul had begun hosting their own “Oriental” costume balls in which the carpets of local Jewish rug merchants lined the walls. And when correspondents from the Judeo-Spanish press of the imperial capital reported on the Ottoman exhibit at the Columbian Exposition in 1893, they described it in terms similar to those used by the anonymous commentator on Tifereth Israel’s 1934 Turkish Nights performance, suggesting that the architecture and outfits of those involved in erecting the imperial displays in Chicago had allowed Ottoman visitors to feel that they were being “transported back to their beloved homeland, where they could return once again return to an Oriental life.”7

Even as the decades passed and the children and grandchildren of Ottoman Jews participated in patterns that might seem wholly “American” in another context, they continued to be inflected with a set of particular Jewish, Sephardic, and Ottoman influences that gave such impulses a distinct meaning. This certainly seems to have been the case of the midcentury portrait of a couple that forms part of the archive of the Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel, which shows a man donning a fez of the Al-Malaikah Shriner Lodge of Los Angeles. Here, the man’s fez appears to have taken on a double meaning: it not only identified the wearer with a local branch of the Shriners International but also no doubt served as a means of reaffirming his Ottoman heritage—at least in the context of the Sephardic congregation in which his picture was preserved.

While this blurring of Shriner and Ottoman traditions may have been the exception, descendants of Ottoman Jews continued to perform their imperial heritage in settings both communal and intimate throughout the twentieth century. An image captured of Victor and Sally Abrevaya—the grandparents of UCLA Professor and Maurice Amado Endowed Chair in Sephardic Studies Sarah Abrevaya Stein—offers yet another example of this phenomenon. The photograph shows the couple sitting outdoors on what appears to have been a characteristically balmy Los Angeles afternoon in 1969. Victor is wearing a fez that looks too new to have been an inherited object passed down in the family. More likely, he had bought it to celebrate a Turkish Night or similar occasion in the community or among relatives. Clearly by this point doing so was in and of itself a kind of local tradition—one with roots many decades in the making. The suggestion that Ottoman Jews had to follow the stark choice of either becoming American or remaining Ottoman failed to capture a reality that was much messier and much more interesting.

Citation MLA: Cohen, Julia Phillips. “American Days, Turkish Nights.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/american-days-turkish-nights/.

Citation Chicago: Cohen, Julia Phillips. “American Days, Turkish Nights.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/american-days-turkish-nights/.

About the Author:

Julia Philips Cohen is an Associate Professor of Modern Jewish History at Vanderbilt University… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 “One Century in the Life of Albert J. Amateau, 1889–: The Americanization of a Sephardic Turk,” interview conducted by Rachel Amado Bortnick, 1986; transcript completed March 1989, 25; Klaus Kreiser, “Turban and Türban: ‘Divider between Belief and Unbelief’—A Political History of Modern Turkish Costume,” European Review 13: 3 (2005), 451.

2 Julia Philips Cohen, Becoming Ottomans: Sephardi Jews and Imperial Citizenship in the Modern Era, (New York: Oxford, 2014), 135-137. On cafés and restaurants, see, for example: Aviva Ben-Ur, Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History (New York: New York University Press, 2009); Devin Naar, “From the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’ to the Goldene Medina: Jewish Immigration from Salonika to the United States,” American Jewish History 93, no. 4 (December 2007): 435-473; Işıl Acehan, “Ottoman Coffeehouses in the United States: the Development of a Transnational Community in Eastern Massachusetts,” in The Transnational Turn in American Studies: Turkey and the United States, ed. Tanner Emin Tunc and Babar Gursel (Bern: Peter Lang, 2012), 155-168; Devin Naar, “Turkinos Beyond the Empire: Ottoman Jews in America, 1893-1924,” Jewish Quarterly Review 105, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 174-205. For a report on a Sephardic restaurant in Los Angeles specifically, see: “Odd Restaurant Obtains Main Street Lease,” Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1924, D4.

3 Although Ottomans of various backgrounds played an important role in the expansion of the oriental carpet trade in the United States, Armenian participation in the trade is perhaps the best known. On this, see “America’s Trade in Oriental Rugs,” Upholsterer and Interior Decorator, Feb. 1920, 54; Robert Mirak, Torn between Two Lands: Armenians in America, 1890 to World War I (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984); Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, “Collecting the ‘Orient’ at the Met: Early Tastemakers in America,” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 69–89. For Ottoman Jews’ involvement with oriental goods in the U.S., see Marc Angel, La America: The Sephardic Experience in the United States (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1982), 143–44; Joseph M. Papo, Sephardim in Twentieth Century America: In Search of Unity (San Jose, Calif.: Pele Yoetz Books, 1987), 21, 29–30, 277; Rıfat Bali, Anadolu’dan Yeni Dünya’ya: Amerika’ya İlk Göç Eden Türklerin Yaşam Öyküleri (Istanbul: İletişim, 2004); Ben-Ur, Sephardic Jews in America, 23, 29, 49, 131, 287; Cohen, Becoming Ottomans, 135–37; Julia Philips Cohen, “The East as a Career: Far Away Moses & Company in the Marketplace of Empires,” Jewish Social Studies 21, no.2 (Winter): 35-77.

4 An undated report from the temple’s bulletin published in either 1988 or 1989, in Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel Archive, UCLA Library Special Collections.

5 Quataert, Donald, “Clothing Laws, State, and Society in the Ottoman Empire, 1720–1829,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 29, no. 3 (August 1997): 403–425. Although infrequent references do exist to Ottoman Jewish women who sported veils during the late imperial era, there is little question that the practice would have been most commonly associated with Muslim women. For an analysis of the self-representation of late Ottoman Muslim women, including the diverse approaches they took to the question of whether and how to veil or cover their heads, see: Nancy Micklewright, “Late Ottoman Photography: Family, Home, and New Identities,” in Transitions in Domestic Consumption and Family Life in the Modern Middle East: Houses in Motion, edited by Relli Schechter (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 65-83.

6 See, for example, the Homelands Exhibition held in Rochester, New York in 1920. By offering folkloric portrayals of each of the groups it featured, the exhibit sought to celebrate the cultures of different European immigrant groups in the region.

7 Julia Phillips Cohen, “Oriental by Design: Ottoman Jews, Imperial Style, and the Performance of Heritage,” American Historical Review 119, no. 2 (April): 364-398; Cohen, Becoming Ottomans, 70.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.