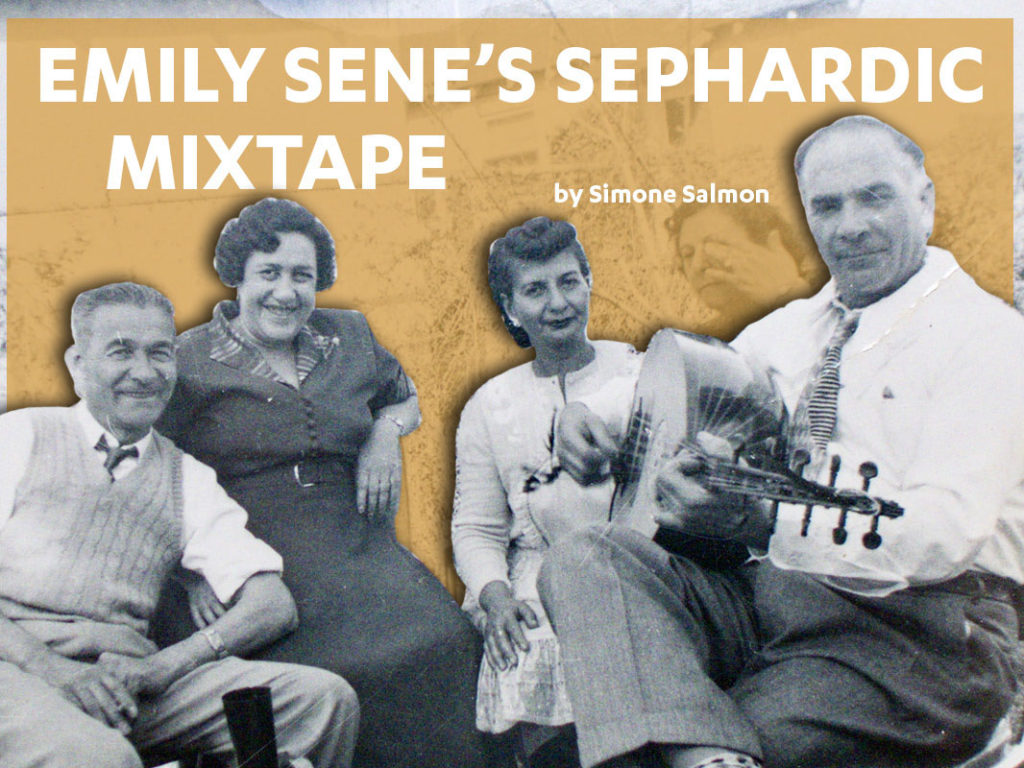

Between the 1940s and 1970s, Sephardic Jews would gather to play and hear Ladino tunes played live by Greek, Turkish, Armenian, and Jewish musicians at weekly picnics in Ladera Park and Veterans Park in the South Bay. The park was nicknamed “Turktown” by those who attended them, most of whom had left the Ottoman Empire during its transition into the Republic of Turkey and other successor states.

These picnics provided a space for Sephardim to perform and listen to familiar lyrics and melodies together. The styles in which the musicians performed these songs involved borrowing melodies, musical modes, and instrumentation, what musicologists describe as contrafact–the practice of layering new melodies and sounds over pre-existing ones–used widely by Sephardic musicians across the globe. By imposing Ladino lyrics on extant melodies from the various areas in which they lived, Los Angeles Sephardic Jews brought to America stylistic traces of the land and relationships they had left behind, enabling them and their audiences to find meaning, comfort, and belonging in their new homes. The practice was one of the key vehicles by which they strengthened their shared identities and created a distinctly American Ladino musical tradition.

Isaac Sene, my great grandfather, was the oudist and singer who led the weekly picnics and whose performances comprise the bulk of the recordings in the Emily Sene Collection at UCLA. Recorded and compiled by his wife, Emily Sene, the collection holds a rich trove of lyric sheets, notebooks, and recordings of the songs that accompanied Sephardic immigrants in the early twentieth century. The collection includes both popular songs and folk melodies, most recorded at Ladera Park.1

Here I trace the path of my grandparents—and Ladino music—from northwest Turkey to Cuba to the United States. I consider the indelible influences those journeys imparted on the Senes’ musical oeuvre, and provide a series of songs drawn from the Sene Collection to demonstrate their use of contrafact as a technique for bridging divides between the Sephardic and surrounding cultures.

From Havana to the Lower East Side

Born in Edirne, Isaac Sene was said by his family to have left Turkey in order to avoid mandatory military conscription at the start of the Balkan wars that preceded World War I. Although his family was relatively wealthy, his mother was unable to sustain the family after her husband became a soldier and after a visiting aunt found the family passed out on the floor from starvation, she moved the family to Istanbul in the hopes of finding a way to make a living. From Istanbul, Isaac made his way to Cuba where he met Emily (née Amada Perez), who had left her hometown of Churlú (Çorlu) at the age of fourteen to join her brothers in Cuba in 1925.

Owed to the severe immigration quotas imposed by the National Origins Act of 1924, Cuba became a popular destination for would-be Jewish immigrants as they waited to gain entry to the United States. These quotas impacted Jewish from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East most acutely: Aviva Ben-Ur has estimated that only 100-300 Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews combined were admitted annually after 1924.2 Home to an organized Jewish community since the earliest days of Cuban independence, Havana’s Jewish population swelled in the 1920s to around 20,000, many of whom were Sephardim from former Ottoman lands. Sephardic Jews maintained their own synagogue, Shevet Ahim (f. 1914), as well as relief organizations and social clubs. Emily, who loved music and dancing, met Isaac at a Sephardic dance in Havana where he was playing the oud.

After countless disputes with the esuegra (mother-in-law) the two finally received counterfeit visas. Emily and Isaac moved together to New York City, where they married on the famous Orchard Street on the Lower East Side in the 1920s. While traditionally recognized as home to Yiddish-speaking, Eastern European Jews, the neighborhood was also home to a kolonia (colony) of a few thousand “Turkinos”—Jews from the Ottoman Empire—by the time of the Senes arrival.3 Like many other immigrant communities in the United States, these “Turkinos” often formed “hometown” societies based on the regions in which they had lived in the Ottoman Empire—such as Salonica, Izmir, Istanbul, Rhodes–that tended to live near one another and sometimes transplanted themselves as groups into other neighborhoods. They often spoke regional dialects as well: at one point, 22 variants of Ladino were documented in New York City.4 But over time, these micro-communities mixed, blending many different linguistic and cultural traditions into a single Sephardic communal identity. They pooled resources to assist Sephardic immigrants, who faced discrimination within and without the Jewish community, held classes in English, and provided medicine to the sick. Language played an important role in the process: as captured in the masthead of the handshake that appeared atop the Ladino newspaper La Vara, the American Ladino press believed they should work to unite the Ladino-speaking public and by the 1950s, had developed a standardized form of Ladino with fewer Turkish words and many borrowed words from French and English.5

Music also played an important role in the consolidation of Sephardic identity. Various aid organizations taught music classes in which they shared songs and developed a collective repertoire. These songs mixed both familiar, old-world influences and new ones, reflecting the diverse cultural influences that converged in the Lower East Side. Ladino music came to bind Sephardim together “so that they [understood] themselves as belonging to each other.”6

Isaac Sene, who possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of Ladino songs, was frequently asked to perform at events from what Emily called “all four communities,” meaning Turkish, Greek, Arab, and Hispanophone.

An example from the Sene Collection provides a glimpse of his diverse musical influences in this period. The melody is said to have originated as a Turkish operetta but appears today in Serbia, Albania, Bosnia, Romania, Hungary, Egypt, Syria, Iran, and elsewhere.7 The first U.S. commercial recording of the melody was performed by the famous klezmer clarinetist Naftule Brandwein, who gave the song the Yiddish-language title of “Der Turk in Amerika,” evidencing a Jewish-Ottoman connection that went beyond the realm of pan-Ottomanism. Likewise, lyrics blending Arabic, French, English, and Italian are sung to the same melody as “Fel Shara” in North Africa, while the tune has also been incorporated in Shabbat prayers. Emily’s recorded version duly employed the technique of contrafact, grafting Ladino lyrics onto the familiar melody to recreate the Turkish “Üsküdara” as “Eskidara.” Owing to the fact that Ottoman-Sephardic musicians interacted frequently with their surrounding cultures, it was natural for music to be shared across the different millets (“religious communities” or “peoples” as defined by the Ottoman state). Audience members in the South Bay likely also sang lyrics in a multitude of languages when they heard Isaac Sene perform.

While her original recording is unavailable, my Ladino ensemble recorded a version of the tune with the first verse in Turkish and the following in Ladino.

At the same time that a pan-Ottomanism was observed in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the area contained a greater swirl of cultural influences within and outside of Jewish culture that provided unique lyrical material for the Ladino song tradition. The products of these interactions in New York City was carried with the Senes as they made their way to Los Angeles.

From the Lower East Side to the City of Angels

After years of struggling to make a living in New York City through the depths of the Great Depression, Isaac and Emily moved with their two daughters to Los Angeles in 1942. There they found a vibrant Sephardic community and quickly became actively involved. Isaac became president of the Sephardic Cultural Club and began convening his weekly “Turktown” picnics at Ladera (and sometimes Veteran’s) Park. He frequently played “Turkish nights” and other Sephardic social functions and lifestyle events across L.A.

Mayesh’s secular recordings were almost always products of his contrafact practices: he took popular Turkish and Greek melodies and put his own, original Ladino lyrics onto them.9 Mayesh recorded his version of the song “Misirlu,” a melody that was shared throughout the Middle East and has lyrics set in Turkish, Arabic, Greek, Armenian, and Persian, about an Egyptian girl (Mısırlı in Turkish means an Egyptian person, paired with the Greek feminine ending of “ou”). Jack Mayesh set the song to Ladino lyrics and released it from his own label in the Elecro-vox studios in Hollywood in 1941.

The same melody of “Misirlu,” was later picked up by surf rock bands in the South Bay after half-Lebanese guitarist Dick Dale re-introduced the song in 1962.10 The tune is still performed widely today by surf rock guitarists and Middle Eastern ensembles alike, in some cases with baglama saz players in Turkey frequently taking inspiration from the surf rock recordings that emulate Turkish tradition.

Mayesh’s recordings are mixed into the Sene Collection alongside Emily’s recordings of the “Turktown” picnics, suggesting that the Senes became an integral part of his distribution network in Los Angeles and the South Bay. Emily made her own mixtapes, which included recordings in Ladino but also contained many songs in Turkish, Greek, and Arabic. One such favorite of hers was Jewish singer Roza Eskenazi’s “Rambi Rambi,” a popular belly dance song in the Greek Rebetiko style. Roza recorded the song with Turkish lyrics, but the song has also famously been recorded in Greek by a multitude of singers.11 The universality of this song among Americans of Ottoman origin speaks to the fantasy of tolerance and brotherhood that was practiced as a holdover from imperial Ottomanism, helping musicians and audiences to find belonging with each other.

Despite their conservative nature, Isaac and Emily’s home was full of belly dance LPs boasting explicit album covers. Isaac was also offered gigs performing for the Arab community. As Isaac had extensive experience performing gigs for the Arab community, the reel-to-reel recordings that Emily put together contain a number of Arab songs by commercial performers such as Mohammed El-Bakkar & His Oriental Ensemble. Sephardic men could typically be found listening to Bakkar while playing shesh besh (backgammon) together. Bakkar, in his kitschy and Orientalist style, had worked as an actor in self-produced and self-directed motion pictures, performed for the Kings of Egypt and Saudi Arabia as well as the Shah of Iran, and had a history of entertaining Syrian, Lebanese, Turkish, and Persian audiences.12 Born in Lebanon, he moved to the United States in 1952 and settled in Brooklyn. “Ya Habibi,” translated to “My Love,” was the first track on his famous 1958 album Sultan of Bagdad. Not only were they valued by Emily Sene and her family, but Bakkar’s recordings were integral to the sonic backdrop to Southern California’s Sephardic musical culture. His records can still be found in local vinyl shops and thrift stores today.

On Vacation at the Hotel Havana

Emily began to record Isaac singing and playing when, only five years into their marriage, she noticed his mental health declining as his Alzheimer’s slowly crept into their lives. At first she would hide a tape recorder under the table or the sofa so that she could preserve his talent in her memory without his noticing. Over time, she started to collect and transcribe Ladino lyrics from women and men in the different neighborhoods and towns through which the two of them traveled so that he had something to look to in case he forgot the lyrics while singing. Every summer, they would go on musical tours across the country in a camper that they had purchased. These trips often ended in Miami, where Isaac would accompany Victoria Hazan and perform with local Sephardic musicians. As soon as Isaac and Emily arrived at their hotel, swarms of people would come to hear him play. Their daughter, Rachel, tells me that once, when playing indoors at a full venue, 200 people left outside were so eager to get in that they succeeded in breaking down the venue’s doors.

Miami provided Emily and Isaac opportunities to interact with Cuban émigrés and exiles as well as Cuban Jews descent. The years they had spent in Havana before coming to the United States were significant ones in their lives and they had absorbed a sense of Cuban identity. The Jewish embrace of Cuban identity in Cuba is obvious even as the population there declined rapidly after the Revolution. In Havana’s largest synagogue, a bust of José Martí stands alongside framed pictures of Maimonides and Einstein. Martí, a revolutionary leader of the nineteenth century who organized Cuba’s liberation from Spain, was said to have “admired Jewish values.”13 By the time the United States had created a permanent naval base in Guantánamo, Martí had already died in battle, but his poetry was memorialized as indispensably Cuban. Selections of his “versos sencillos” were used to form the popular song “Guantanamera,” an essential anthem for the Cuban state and an expression of Guantanamo’s culture.

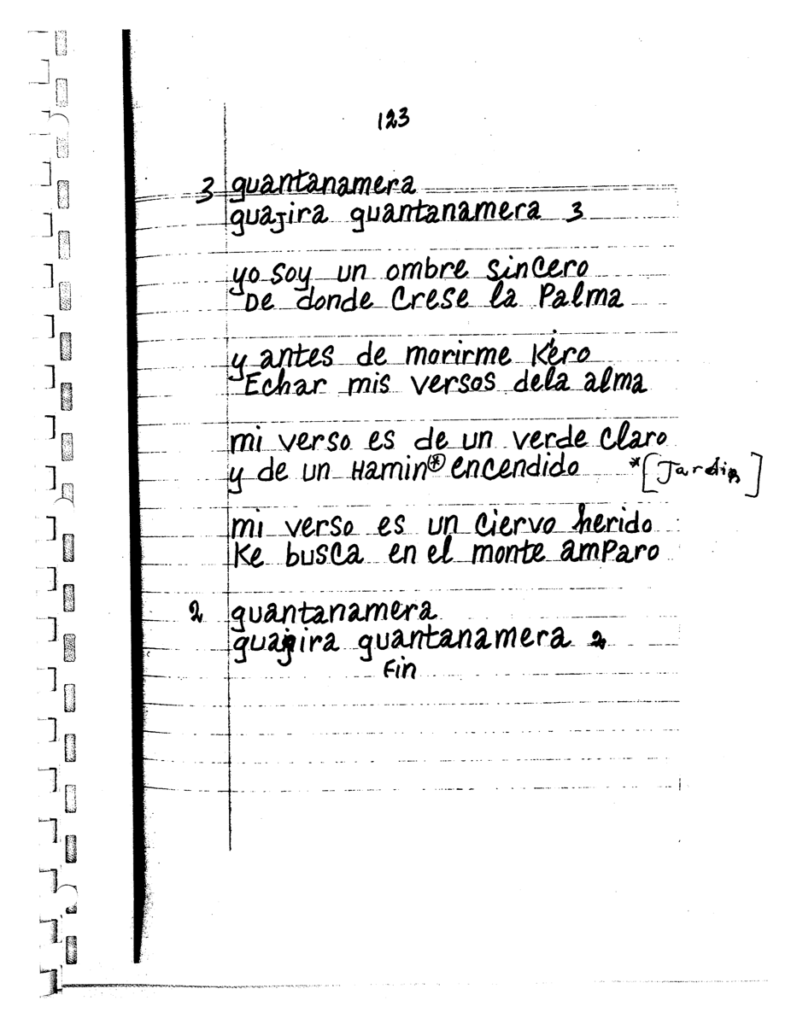

Isaac Sene’s “Guantanamera” had lyrics closer to Martí’s verses than the popular version does today. Along with documenting its form before the Sandpipers 1996 hit recording, Emily documented its Judaicization with her substitution of the word “hamin” for “carmín.” She later added an “i” to the word “kero” to make it sound Spanish instead of Ladino.14 Emily’s recordings of “Guantanamera” captured a moment in time before wide-scale distribution of Cuban commercial recordings had reached American homes. As Emily’s homemade tapes of Isaac piled up over her years of recording him, one can hear that the California and Florida audiences often attempted to sing the melody as it was heard on American radio. Below is a recording of “Guantanamera” featuring Isaac Sene singing and playing his oud.

Listening to the recordings and examining the notes in the collection Emily Sene compiled makes my great grandparents’ lives tangible: I can travel through my family history sonically as I am placed in different times and locations, at various family events, and in her most intimate and guarded encounters. The range of soundscapes in the Emily Sene Collection reveals that along with the advent of commercial recordings like those made by Mayesh, Bakkar, and Eskenazi—and their international distribution by record companies such as Odeon and Columbia—Emily’s distribution of her various recordings of her husband, her mixtapes, and her commercial 78s, 45s and LPs allowed these songs to reach entirely new audiences, both locally and around the world. Her deep love of music echoes across her notebooks and tapes:

Recuerdos de nuestras madres y de nuestros padres. Yo Emily Sene, nacida en Estambol en un pueblisico que se llama Churlú. Yo nací al 1911. Al 1955 empecí a recoger estas canticas y romanzos de Haim Effendi, que era famoso por el mundo entero. Por recordarnos a nuestras madres las escribo y se las do a mi marido, que es professional de ud y cantador, para que me las cante y quitarlas a las plazas que todos las canten ‘ternamente’.

Memories of our mothers and our fathers: I, Emily Sene, was born in Istanbul in a neighborhood called Churlú. I was born in 1911. In 1955 I began to collect these canticas and romanzos of Haim Effendi, who was world famous. I write for the memories of our mothers and for those of my husband, who is a professional singer and oud player, for him to sing to me, and to take them to the streets so that everyone will sing them eternally.15

Citation MLA: Salmon, Simone. “Emily Sene’s Sephardic Mixtape.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/emily-senes-sephardic-mixtape/.

Citation Chicago: Salmon, Simone. “Emily Sene’s Sephardic Mixtape.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/emily-senes-sephardic-mixtape/.

About the Author:

Simone Salmon is a graduate student in the Ethnomusicology Department at UCLA … More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 The Sene Collection is part of the Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel (STTI) Archive at UCLA Library Special Collections. It contains nearly 200 audio recordings on cassette and reel-to-reel. For more details, view the finding aid for the STTI Archive at the Online Archive of California.

2 Aviva Ben-Ur, Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History (New York: New York University Press, 2012), 25-27.

3 Devin Naar, “Turkinos beyond the Empire: Ottoman Jews in America, 1893 to 1924,” Jewish Quarterly Review 105, no. 2 (2015): 187.

4 Devin Naar, “From the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’ to the Goldene Medina: Jewish Immigration from Salonika to the United States,” American Jewish History, 93, no. 2(2007): 466. Naar cites an article from The World, “Finds 22 Dialects of Spanish Jews Here,” an undated clipping that appears in the archive of Henry V. Besso, box 7, folder 19, American Sephardi Federation. Hometown associations did not always organize according to rigid geographical boundaries. Solomon Emmanuel, from Jerusalem, and Albert Levy, from Salonika, presided over societies of Jews from Mo nastir, whereas those from Kastoria joined an organization of Jews from Ioannina before establishing their own. See Joseph M. Papo, Sephardim in Twentieth Century America (San Jose: Pele Yoetz Books, 1987), 30.

5 Ben-Ur, Sephardic Jews in America, 30.

6 Rolf Lidskog, “The Role of Music in Ethnic Identity Formation in Diaspora: A Research Review,” International Social Science Journal 66 (2017): 219-20, 25.

7 Judith Cohen, Dans mon chemin j’ai rencontré. 1997. Transit Records. B001DLG3XS

8 The five include Kaliphone Records, Me Re Records, Metropolitan Recording Co., Polyphon, and Mayesh Phonograph Record Co.

9 Mayesh was perhaps most famous for his treatment of the Turkish song “ah sevgilim bülbülüm” (sung in Greek as “To Kanarini”) titled “Ven Canario,” and released by Me Me Records.

10 Dick Dale made famous the “alternate picking” or “double picking” technique used to sustain notes when playing. I assert that he transferred this technique from the oud to the guitar.

11 Along with Turkish, Roza Eskenazi was also known for singing in Greek and Armenian.

12 King Farouk of Egypt, his successor, Maj. Gen. Mohammed Naguib, and King Ibn Saud; from 1958. Sultan of Bagdad: Mohammed El-Bakkar and his Oriental Ensemble. Music of the Middle East Vol. 2. Audio Fidelity: AFLP 1834. 33rpm LP.

13 Ruth Behar, An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 76, 131.

14 It was common for Emily Sene’s lyrical transcriptions to switch between Spanish and Ladino spellings, but she always opted to keep Spanish words rather than to change them to their Ladino counterparts. This was likely because, as a woman without proper schooling in literacy, she wished to conform to the societies which she inhabited. This is concurrent with the rules of assimilation according to the Jewish tradition.

15 As appears in Rivka Havassy’s unpublished journal article provided to the author. Translations are my own.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.