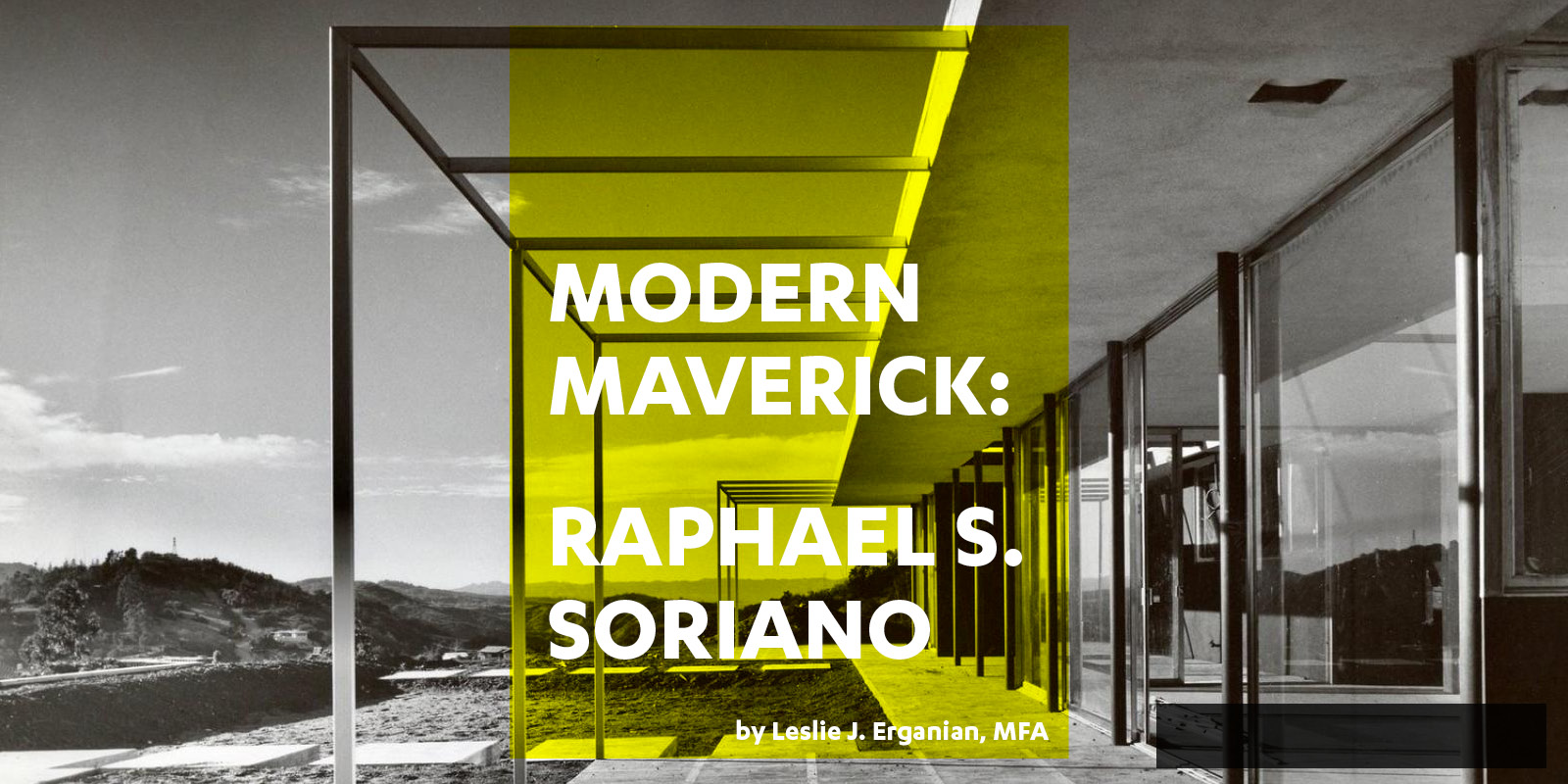

Midcentury modern architecture, one part of a design movement that encompassed interior, product, and graphic design, remade Los Angeles’ aesthetic sensibility as well as its built environment. Jews were prominent creators and consumers of the midcentury modern ideal; among its progenitors was a Sephardic Jew from Ottoman Rhodes, Raphael Simon Soriano.

Raphael Simon Soriano was born on August 1, 1904, on the island of Rhodes in the Aegean Mediterranean. Conflicting accounts give his year of birth as 1907, but existing documents agree on the year as 1904. It is more than likely that Soriano, himself, was the source of the conflicting date, as it erased the first few years he spent as a new immigrant in America, struggling to find a profession in which his gifts could flourish. That gift proved to be architecture. Soriano would become one of the leading contributors to the development of California midcentury modern architecture, with Los Angeles representing the city in which the best of his work came to flourish.

Raphael’s mother’s family, the Codrons, had been driven to Rhodes from Spain as a result of the expulsion of Jews during the Spanish Inquisition in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The island of Rhodes, Greek prior to 1500, had fallen under Turkish rule and the Codrons, along with other displaced Sephardic families, had taken refuge in the old fortress area of the capital city where they established the judería (Jewish quarter). Rebeca Bohara Codron, Raphael’s mother, was born in the judería, the eldest of eleven children, only seven of whom survived. Born at a time and in a place where education spent on a woman was considered wasted, Raphael’s mother was illiterate until after her marriage to Raphael’s father, Simon Soriano.

Simon Soriano’s grandfather had been born on the French side of the Pyrenees in Bayonne, in the Southern part of France—Basque country. His family had also found its way to the judería of Rhodes as a result of the Spanish Inquisition. Simon, Raphael’s father, was born in this quarter, just as his mother had been. It is here that they met, married, began a household, and had three sons of their own, Vittorio (Victor), the oldest, Alfredo (Alfred) the youngest, and Raphael.

Throughout his childhood, young Raphael was exposed to many languages, the first of which was his mother’s native tongue, Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish. Raphael’s father taught him to write and speak Greek fluently, and his grandfather gave him lessons in French and Latin. Raphael was also exposed to Italian after Rhodes came under the occupation and rule of Italian forces in May of 1912, during the Turco-Italian war.

Raphael was also exposed at an early age to music, which he not only grew to love, but which would ultimately give him the underpinnings of his belief system regarding architecture. Raphael’s mother loved music, and he recalled having heard her sing romanceros in the house. It was not unusual for the Rhodeslis women who were Rebeca’s contemporaries, to be able to sing fifteen ancient romantic ballads with astonishing fidelity to the Spanish poetic and musical heritage, reflecting both a genuine love of singing and a dedication to rendering each word and every note with detail and precision. Soriano would maintain fidelity to these dual concerns throughout his adult life.

Getting Started in Los Angeles

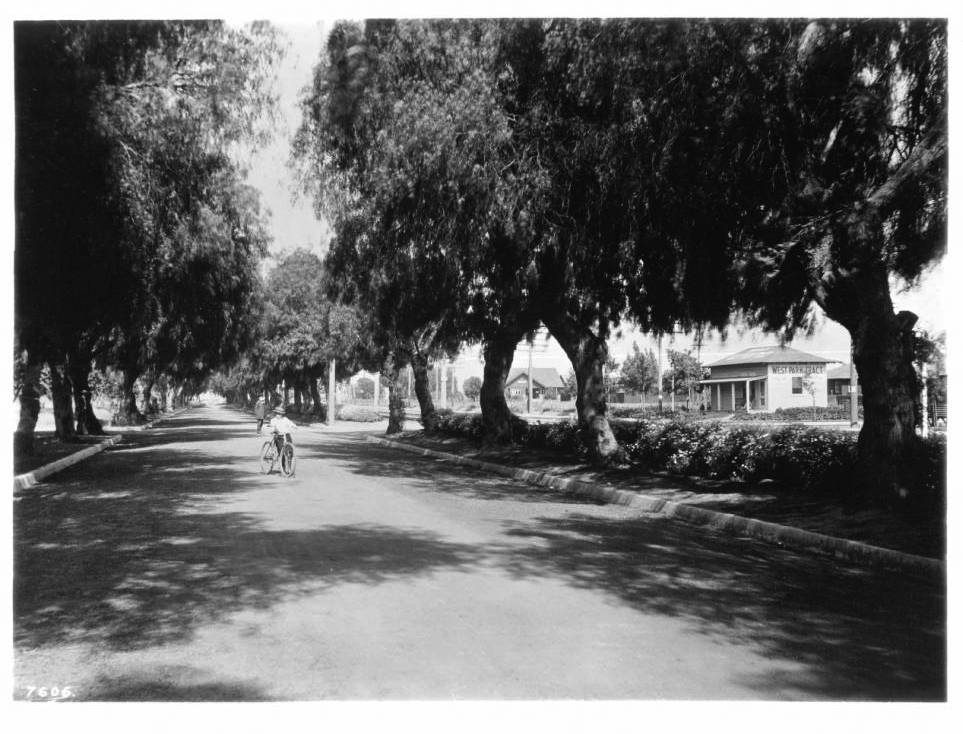

By 1924, Soriano, having completed all levels of schooling that Rhodes had to offer, had the ambition to continue his studies overseas. With two aunts already in Los Angeles, he was determined to join them. Finally arriving in California after a trans-Atlantic ship crossing and trans-continental train crossing, Soriano was delighted to find something of the familiar in what was to become his new home, “Rhodes is full of flowers; beautiful things really. And Los Angeles was very close: oranges and the orange blossoms I love,” Soriano later recalled. This was still a time of cerulean skies and grass covered hillsides. “California was a little village then. Especially Los Angeles.”1 Using his aunt’s home on Santa Barbara Avenue (now Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd) as a base, Soriano soon took a job in the produce department at the L.A. Grand Central Market on the Hill Street side and quickly resumed what he continued to see as his responsibility, sending money home. Soriano also began to nurture his own dream, that of becoming a composer, saving up money to buy a violin and tickets to classical concerts whenever possible.

Trading up his Grand Central Market job to work at a fruit stand in front of the Clark Street Hotel, Soriano began to sell fruit to the musicians that stayed there, frequently recognizing them from a Los Angeles Philharmonic concert he had attended the night before. When he had finally saved up enough money to buy a copy of a French Maggini from an old violinmaker at Hill and Third, Soriano began to take lessons from a Mr. Hunter whose son-in-law was a violinist for the L.A. Philharmonic, refining what would later become the strict boundaries of his musical palate: a particular taste for Bach, Vivaldi, Flamenco, and certain Czerney exercises, a limited tolerance for “some folklores and dances which are in the same structural scope,” and a decisive distaste for “anything descriptive, anything sort of sentimentally delineated.”

Up two blocks from where he’d purchased his violin on Fifth and Hill Streets, Soriano also enrolled in English classes given by the Los Angeles Coaching School. Mr. Driscoll, a professor of chemistry there, took a liking to him, and invited Soriano to share holidays with his own family. Clear by now that he wanted to continue his education at the university level, Soriano expressed that wish to Driscoll, who introduced him to the Dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Southern California (USC), Arthur Weatherhead, explaining to him Soriano’s facility with language and arithmetic. Unable to recognize his French Brothers College diploma as legitimate, USC agreed to admit Soriano provided he was able to pass a series of exams, which he did easily. “I was admitted, provided I stay in school with a B average,” Soriano later said. Having been told by Arturo Toscanini’s own violinist that even at his level of success, the life of a violinist was financially difficult, Soriano had begun to question the viability of a career as a musician or composer. Consequently, despite his passion for music, “I wanted to be a composer…composition — music — was my greatest joy.”2 Soriano selected a profession with a greater likelihood of providing a substantial income: architecture.

Acquiring a Profession

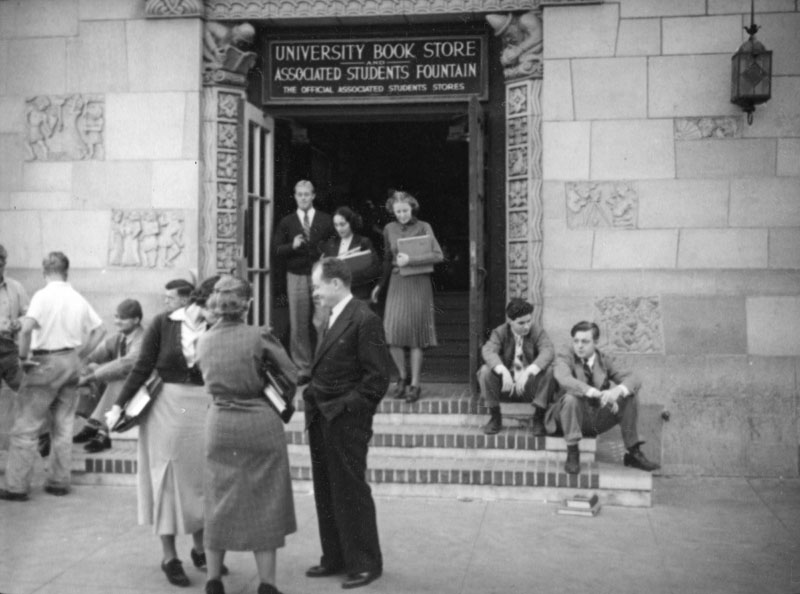

In the fall of 1929, five years after his arrival in the United States, Soriano began classes at USC’s School of Architecture, in a one-story building on 35th Place. As a private school, most of those in attendance were from wealthy families, especially in the School of Architecture. While his fellow classmates appeared to class wearing cashmere sweaters and gabardine or tweed trousers, Soriano appeared in corduroys. Richard Chylinski, who would meet Soriano in his later years, remembered him telling a story about how Dean Weatherhead wanted him out of the school because he did not want any students in his department who had “dirt under their fingernails.”3 Nevertheless, each morning at eight o’clock, Soriano began his full schedule of sixteen academic units, and each afternoon at five, he would arrive for an eight-hour shift at the fruit stand, returning home at one o’clock in the morning for a brief shift of sleep. On occasion, Soriano supplemented his fruit stand income by selling avocados out of his briefcase on campus for one dollar each. Despite his best efforts, by the end of his first month of classes, Soriano was already having financial difficulties. “I was always behind the eight ball—always in debt.” One night at work, a man came up to his fruit stand after a Philharmonic performance, and began speaking with his companion in French. Soriano joined in the conversation and the man, Dr. René Bellé, a professor of French Literature at USC, invited Soriano home for dinner. Soriano became a frequent guest at the home of Dr. Bellé and his wife, Gertrude, enjoying their lively conversations about music and other subjects. “Oh my God, I had finally a friend,” recalled Raphael. Dr. Bellé encouraged Soriano to continue with his education, and agreed to co-sign for his student fees every semester. Dr. Bellé also offered Soriano the opportunity to enroll in French language and literature classes so that should his architecture grades be less than desirable, his A’s in French would pull up his average.

Soriano took a second job in the zoology department drawing foraminifera viewed through a microscope collected from the Galapagos Islands during a John Allan Hancock expedition. An exquisite series of hundreds of Soriano sketches today resides in the Smithsonian Institute. The drawing skills Soriano applied in zoology were simultaneously being employed in his first-year architecture classes. The classical Beaux Arts curriculum offered at USC required the repeated drawing of the classical orders for which he received first mention.

Soriano’s second year at USC posed a challenge. As he described:

“The second year we started getting problems. They gave us the design of a little bank or a little, whatever, a little small building. And I used to try to design them in what my own concept of what architecture should be rather than copy. They used to tell us to design it in English or in French, and I refused to do it. I used to say, “What is a style? That doesn’t mean anything.”

Soriano’s increasingly strong and independent ideas about architecture were not met favorably by his professors, and he was not immune to self doubt:

“Most of the fellows in my class had finished several sheets of working drawings, while I was still struggling with one! There were times I really thought I was stupid!! And the voice of Dean Weatherhead…kept ringing over and over again like a defective record! ‘Soriano you are not talented, it is best for you not to continue with architecture.’”

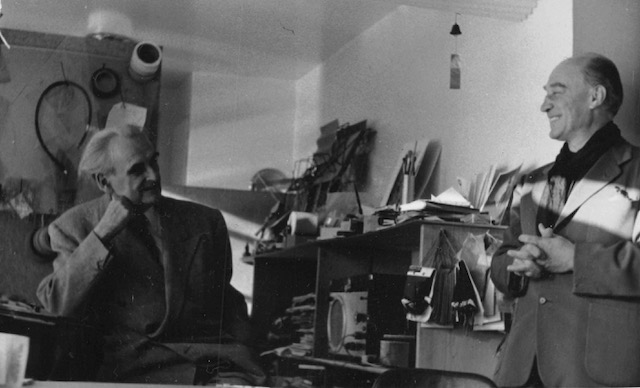

As Soriano’s architectural beliefs began to diverge from USC’s curriculum offerings, he began to seek inspiration elsewhere. A friend suggested that he attend a double lecture given by Frank Lloyd Wright and Richard Neutra at the downtown Philharmonic Auditorium. There, in the embrace of a space whose walls were imbued with music, he was introduced to the charisma of Wright’s personality and the clarity of Neutra’s ideas. Whether this lecture precipitated his Beaux Arts rebellion, or simply offered him support for the direction his progressive mind had already chosen, Soriano must have left the auditorium that night strengthened by the knowledge that he was not alone in his desire to create new forms for architecture beyond the traditions of the past.

By his third academic year at USC, his fellow students had come to recognize not only the vigor and boldness of Soriano’s personality but his unusual strength in engineering. This, coupled with his excellent drafting abilities, made him an ideal candidate for an internship with an established architectural practice. No architect’s views had impressed him more that those of Neutra. Believing him to be the first great American rationalist, Soriano came to him and asked for work in the summer of 1932. Impressed by Soriano’s drawings, Neutra asked him to come work at his Douglas Street studio without pay and accompanied by his own supply of India ink. Soriano seized the opportunity, later avowing that Neutra exerted a “great influence on me,” admiring everything from the clarity and quality of Neutra’s designs to his tremendous sensitivity to colors and textures.

During Soriano’s fifth and final year at USC, Rudolf Schindler came to campus in the hopes of discovering a talented young assistant for himself. Soriano’s thesis project inspired Schindler to offer him a job for a dollar a day but, much to Neutra’s dismay, within months, not even the pay could entice Soriano to remain. Raphael found Schindler’s drawings to be confused, lacking clarity of vision. Soriano returned to Neutra’s office and continued to refine his own vision outside the classroom, in an atmosphere that stimulated him even without pay.

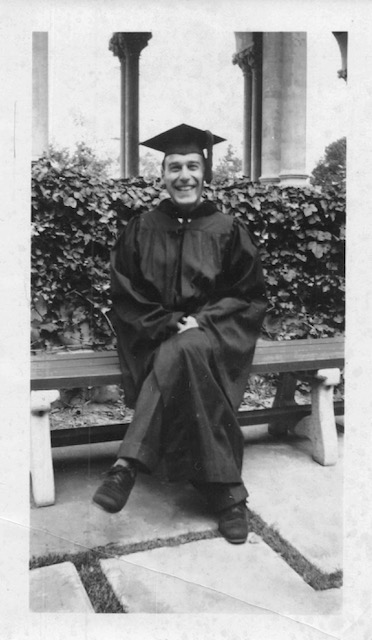

Meanwhile, inside the classroom, despite the repeated attempts of the architecture department to fail Soriano, the straight A’s he received in his French language and literature classes offset his abysmal grades in architecture, and in a ceremony that began at 3:00 p.m. on Thursday, June 14th, 1934, in the Exposition Park Coliseum, Raphael Simon Soriano graduated from USC’s School of Architecture. With the professional credentials he had worked so hard for finally in hand, Soriano, by then nearing the age of thirty, was ready to put his ideas into practice. Acknowledging the difficulty of having reached this moment despite resistance, Soriano later said, “Somehow I have a tenacity and stubbornness in my knowledge, somehow, even though I’m ignorant. Or maybe stubbornness in my ignorance, I don’t know. But somehow I know what I know and what I feel, and what I know, it was right.”

Practicing Architecture

The timing of the world is not always in line with personal ambition and despite his readiness to work, Soriano had graduated into the Depression. The only job available to him at that time was measuring manholes for the City of Los Angeles. “They put sewer systems—they put manholes, but they didn’t know where they were…so we had to mark them. All the engineers and architects were put to work to mark the manholes in the City of Los Angeles.” By 1935, Soriano was able to trade his city job for a county position in the engineer’s office. There he worked on three Los Angeles-based projects funded by the Work Progress Administration (WPA), one of the programs of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Soriano worked closely with the county architect, Cassatt Griffin, who educated him in the low-cost construction method of framing with wood. This position saw him through to the spring of 1936.

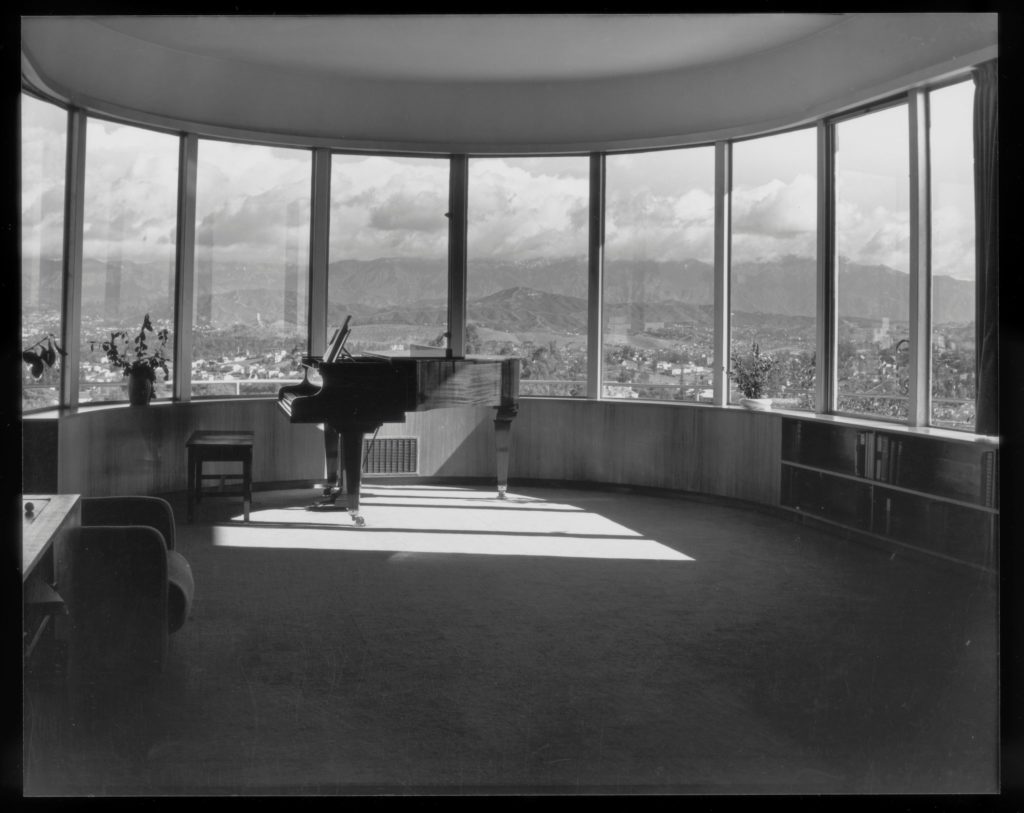

That same year, Soriano was offered his first architectural commission. Hungry to see a European film, Soriano had attended a John Reed Club screening of “Le Miracle de Saint-George.” This hilarious French satire had Soriano translating jokes for a woman seated behind him, Mrs. Orkin, who in a show of gratitude, offered him a ride home. En route, she discovered his love for music and consequently invited Soriano to hear an upcoming piano concert to be given in six months by her cousin, Helen Lipetz. Soriano attended and afterwards entered into a lively conversation with Helen and her husband Emmanuel, so dazzling the couple with his extensive knowledge of music that they commissioned him to design their house around her Bechstein grand piano. The Lipetz House, completed in 1936, not only thrilled his clients, but also gained Soriano worldwide recognition. Sixty-five years later, this award-winning house still stands.

Meanwhile, the situation back in his native Rhodes was darkening as the forces of World War II gathered. Turkey finally formally ceded control of the island to Italy in 1923, just as a new fascist government took control of the country. In 1936, a new fascist governor was installed in Rhodes who, following Mussolini’s alliance with Hitler, began implementing new antisemitic laws. Personal correspondence indicates that Soriano was aware of the increasingly dangerous conditions for family members who remained behind.

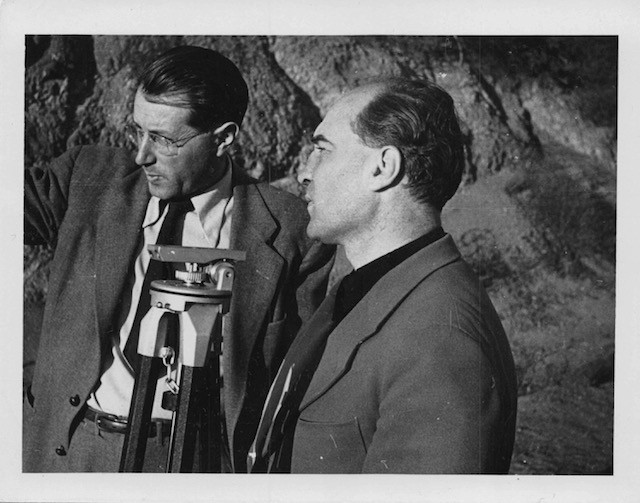

The year 1936 also brought Soriano the acquaintance of a man who would prove to be significant throughout the remainder of his lifetime: the young architectural photographer Julius Shulman. Sensing that they might be simpatico, Neutra had arranged for Julius to meet Raphael at the then under construction Lipetz house. Shulman described their encounter:

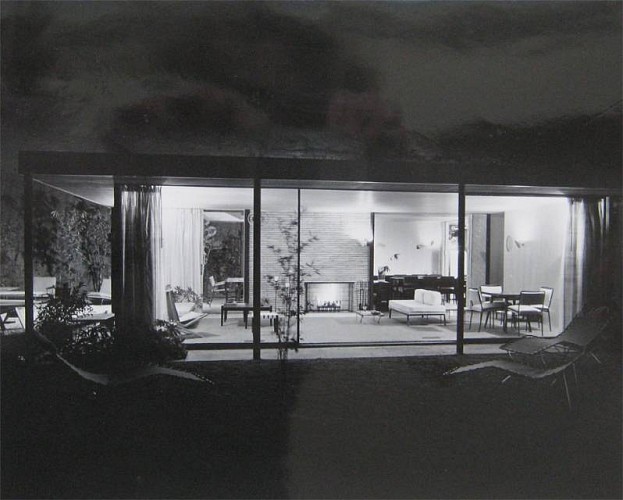

“At the location I met Raphael Soriano, sitting on the newly-carpeted living room floor eating lunch. I shared a sandwich with him and described my meeting with Neutra, which surprised him. Neutra, he stated, was a tyrant with photographers. That utterance, was followed by his asking, ‘would you photograph this house when it is completed?’ Not only did I photograph this house several months later, but subsequently its publication in this country and abroad served to showcase Soriano’s design and my talents. Now, in retrospect, I have revisited that fateful day in March 1936. Our friendship continued during ensuing years when I photographed all of his projects. In 1947, acquiring land for a future home and studio, I asked if he would design them for us.”4

Soriano’s recollection of the genesis of the Shulman house commission was slightly different. As he described:

“Julius wanted to invite different architects to each design a room. I said ‘Julius, that will never be, because nobody will do that. That’s not going to work any more than to have ten chefs do one meal.’ He came to me and says, ‘Soriano, I think I’ll select you to do the..’ And I said, ‘Fine, thank you.’ And I did.”

The playful differences in Soriano and Shulman’s recounting of the same event underscores what can often be said about those at the leading edge of their respective professions: they have healthy egos, which can sometimes lead to clashing perspectives. In this particular case, however, Soriano’s clarity of vision as an architect was matched by Julius’s unerring eye as a photographer. Equal competencies allowed their professional relationship to sustain itself throughout the coming decades and laid the groundwork for their equally long friendship.

The years between 1936 and 1939 were productive for Soriano, especially considering the wartime constraints on materials usage and building construction. A healthy percentage of the structures Soriano designed were also built. The development of his architectural abilities and demand for his services increased in tandem. These same years also provided Soriano with a social life in the company of other stimulating and creative people. For a time during this period, he lived on the same Hollywood street as Man Ray, Charlie Chaplin, Agnus Varda, and the composer Edgard Varèse. Later reflecting on this period of his life, Soriano remarked, “I was there, you see, right in there. And I was very good friends with Man Ray. In fact, Man Ray did two portraits of me…we had marvelous evenings, marvelous discussions with these people.”

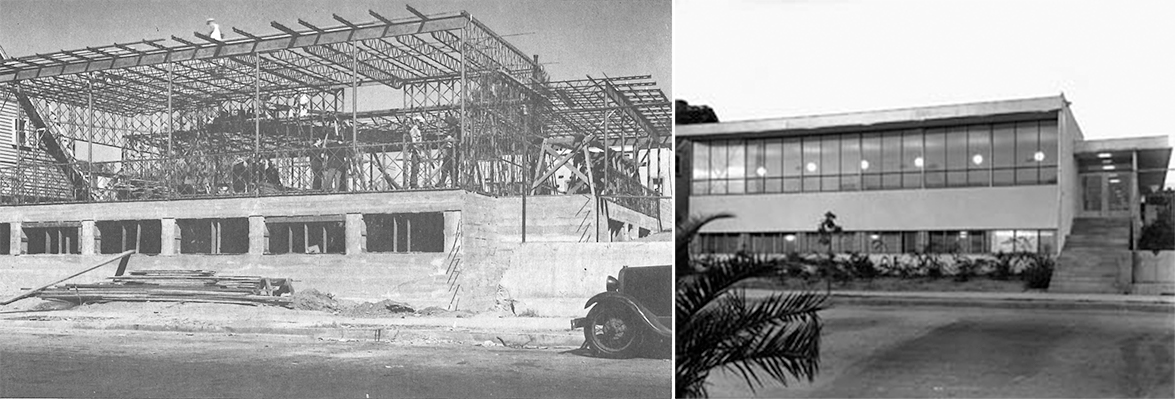

Then, early in 1939, an unexpected incident occurred while on site for the Jewish Community Center in Boyle Heights. Standing in the sloping Soto Street where the project site was located, As Soriano delivered a request to his welder regarding the proper welding of the rivets, a runaway car hit him. Soriano suffered a collection of devastating injuries; broken femur, broken knee, broken clavicle, osteomyelitis of the nose, a lost piece of jawbone, and a cut lip. “They took me in with shovels,” Soriano later recalled of his condition upon entering the hospital. Soriano tenaciously fought to regain his strength during a more than six-month recuperation period while confined to his hospital bed.

The prognosis from the outset was fairly unanimous amongst the doctors in attendance. He was not expected to pull through. During this time, six clients went running. The Nixons were the only clients to stick fast to their commitment. “We believe in you,” they told him. Soriano reciprocated their faith by designing their house from the hospital. Richard Neutra was his most frequent visitor during his hospital stay, a kindness that would cement Neutra in Soriano’s mind as not just a great architect but as a great human being. A letter from a female friend confirms that Soriano had been released from the hospital by August but with a cast that extended up the length of his leg to his waist. “I was solid. With crutches and a cane. For nine months I had that.” His freshly broken nose had permanently altered his handsome face, giving him the rugged look of a seasoned boxer. His leg would give him pangs of pain throughout the rest of his life, but his injuries would do little to alter the course of Soriano’s architectural progress. All three projects designed in the year following his accident were built, and the ensuing years brought increasingly challenging projects and wrought increasingly innovative architectural solutions from him.

The entire decade of the 1940s was highly productive for Soriano, culminating with his Case Study House, the Shulman House, and the Curtis House. This flurry of activity necessitated the hiring of an assistant in the summer of 1950 to execute his Case Study House presentation drawings for publication in John Entenza’s Arts and Architecture magazine, young Pierre Koenig, who reported to work at Soriano’s studio in the summer following his own USC graduation. “It was in Hollywood, an apartment—a crowded apartment. I worked in the kitchen.”5 Dan Dworsky, a fresh architecture graduate from Michigan, also put in time at Studio Soriano that year and would become one of the few individuals to remain friends with Soriano until the end of his life, when he would see to it that Soriano was not placed in a pauper’s grave but that he had a proper burial. Craig Ellwood would be another young architect to come and work for Soriano. Soriano’s reputation had undoubtedly harkened to this select group of young architects. Soriano was considered to be at the time one of the most advanced architects in the world, with his cutting edge technology, design, and planning.

In contrast to Soriano’s new world achievements, the first half of that same decade saw the old world suffering first hand the effects of World War II. Personal consequences included the relocation of Soriano’s parents and brothers, who later made it to America, and the Auschwitz annihilation of nearly all of the remaining Rhodesli Jews including three of Soriano’s aunts. Soriano spoke little on the subject of personal war year events, and original correspondence written in French and Italian from his family members during this period, remains yet to be translated.

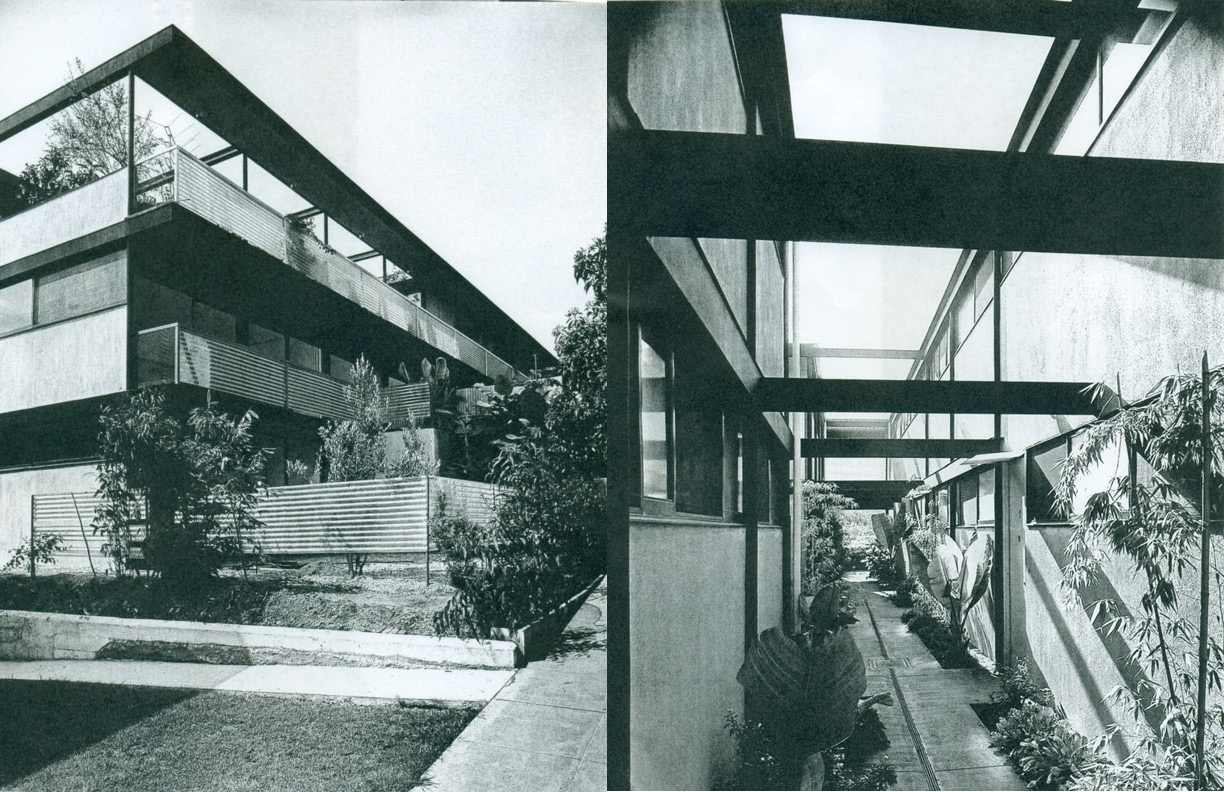

In 1952, two years shy of his 50th birthday, Soriano built the Colby Apartments, which achieved the distinguished recognition of a national AIA award. With this project, Soriano had been as vigilant as ever regarding even the smallest detail of construction. The sloppy work executed by the union laborers to make the cabinetry frustrated him to the point that he contracted his own late night team of two non-union Italian cabinetmakers to finish the job in secret during the wee hours. Soriano later recalled their work ethic:

“They hardly spoke English. And they were the most beautiful people on earth…. They used to rub their hands on their cabinet they’d finished and say, ‘Signore Soriano, guarda! Che bello!’ (‘Look, Mr. Soriano, how beautiful!’). They were proud of what they accomplished. Putting their hands over…such a finesse. As if they did something—which is true, they did a beautiful job.”

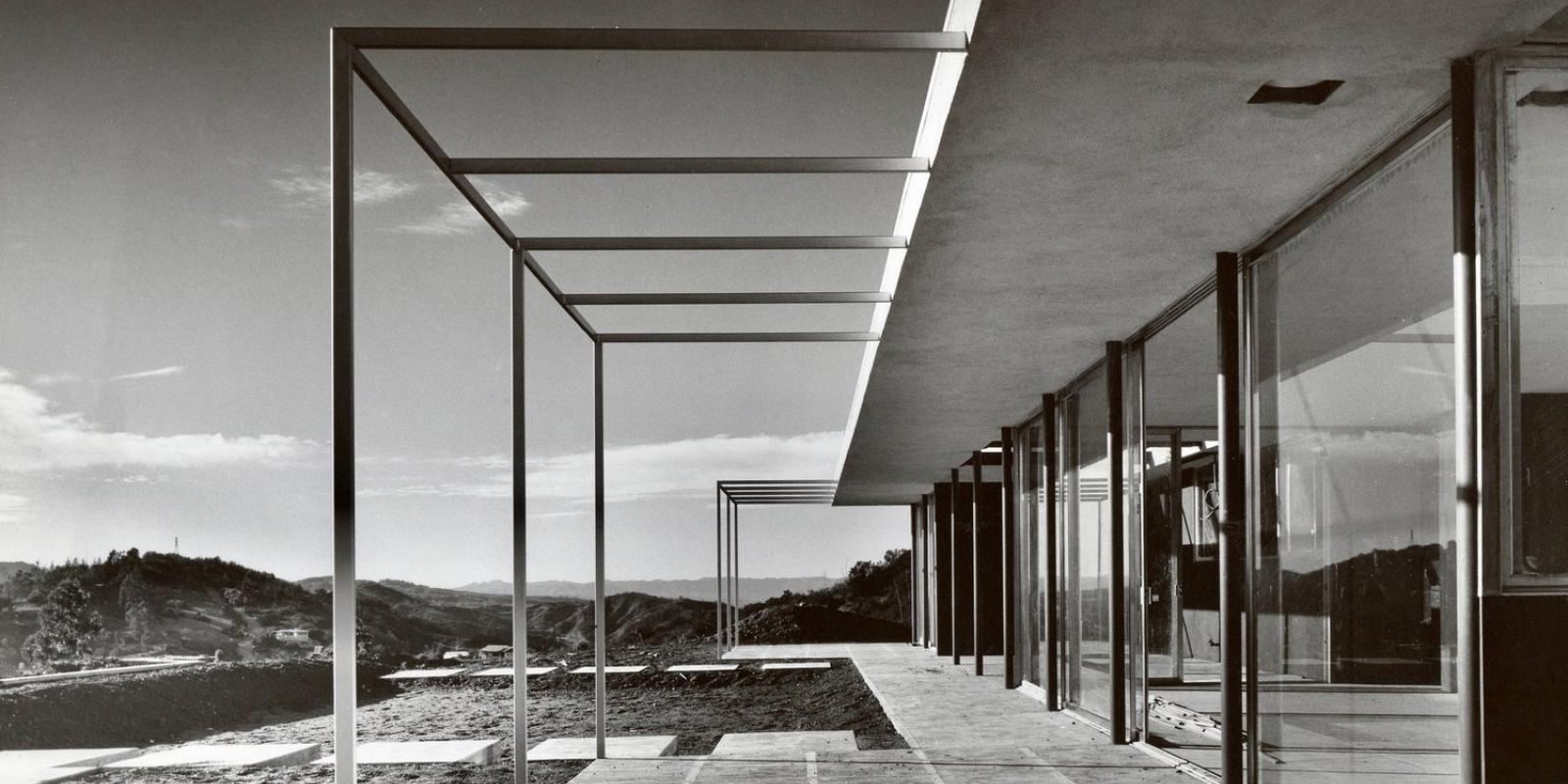

Clarity Through Distance

In 1953, following a complaint to the AIA issued by a client in Bel Air and professional censure throughout Los Angeles, Soriano relocated to Tiburon, north of San Francisco, where he married Elizabeth (Betty) Stephens, the daughter of a powerful San Francisco Judge. There, Soriano established his new practice in a small structure on the Tiburon pier. The years that followed proved productive at the outset, with up to eight architectural assistants and a continuing parade of visitors, including clients, students, and fellow architects, Lloyd Rigler among them. Rigler became Soriano’s client, patron, and life-long friend. Their collaboration from 1953 to 1957, resulted in one of Soriano’s proudest professional achievements, Adolph’s Laboratory and Office Building. Ever on the forefront in his reconsideration of traditional building materials, Soriano went on to design a steel house for developer Joseph Eichler in Palo Alto for which he received an AIA National Award, the Award of Excellence from Architectural Record, and the Northern California AIA Award in 1955. Soriano was made a Fellow by the AIA in 1961.

His first all-aluminum house for Albert Grossman in Studio City California in 1964, led to the development of Soriano’s trademarked all-aluminum building system design called “Soria Structures,” eleven of which were built on the island of Maui, Hawaii, his last realized buildings. In the 1970s, Soriano turned his attention more and more to architectural theory and teaching, traveling the world as a lecturer, writer, and researcher. Soriano’s personality translated into a naturally captivating and provocative on-stage presence throughout the coming years.

When, in 1985, Soriano found himself evicted from his home of 30 years on the Tiburon pier, it was his long-time friend Richard Chylinski, by now chair of the department of architecture at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona, who extended Soriano an invitation to become a Special Sessions Instructor at the university. Soriano flowered as a teacher and inspired a new generation of young architects. In 1986, the Los Angeles branch of the AIA embraced Soriano once again, granting him their AIA Distinguished Achievement Award. USC followed suit with their Distinguished Alumni Award.

Postscript

While conducting research at the University of Pomona Archives in 1999, for my contribution to the Phaidon book, Raphael Soriano, I found in Soriano’s possessions confirmation of a life simply lived. His wardrobe consisted of the bare essentials—a black beret, white turtleneck, dark trousers. In coming across his frying pan, I could imagine the intoxicating flavors he coaxed from it over the years for clients and friends. Within the boxes of personal effects were examples of his beautifully rendered drawings, and multi-lingual correspondence dating back to his American beginnings—letters from his parents in Rhodes, from his brother in the French Belgian Congo, and from acquaintances scattered across the world. Throughout nearly nine decades of life, Soriano practiced what he preached, owning little that was extraneous. There was one small personal indulgence, however: a miniature collection, kept in a black and gold Courtly Soap box, of cancelled stamps from around the globe that included a massing of unsent American 1969 Issue Man on the Moon stamps gently scented with soap. One can only guess at what Soriano must have felt at this achievement, which employed so many of the principles he believed in, and argued for throughout his own life.

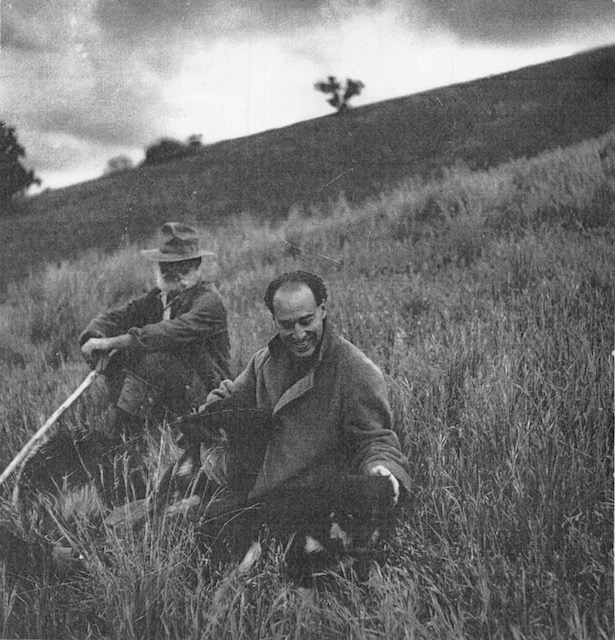

There was also an evocative photograph of a handsome young man sitting on a hillside covered with tall grasses, his right arm firmly wrapped around one dog’s neck, while his left arm vigorously petted another. The dark young man’s smile is so filled with light, that it nearly pushes back the clouds just beginning to threaten the horizon. A shepherd is seated beside him, with arms steadied on raised knees, and hands loosely folded over the top of a long wooden staff. In 1936, Julius Shulman found himself climbing up this young Los Angeles hillside with his then-new friend, Raphael Soriano. Raphael called out to the dogs in Basque, and they came running. Gathering with them in the grass, Soriano held a conversation in Basque with the Shepherd, while Shulman indelibly fixed the moment using silver nitrate and the light of the Southern California sun. Over all other possible images to have selected, this was the same image Julius Shulman himself had chosen for the entry wall of his Soriano designed home, not an image of any singular architectural achievement, but a reminder of their shared Los Angeles beginnings.

In 1988, two weeks shy of his 84th birthday, Soriano died in his sleep. He was buried in a Jewish cemetery in East Los Angeles with a dozen or so mourners in attendance. Would that there had been some way to cheat time and accord Soriano the expectant wish he expressed in one of his later interviews: “Oh, I wish I could live another two or three hundred years to see what is going to happen!”

Citation MLA: Erganian, Leslie J. “Modern Maverick: Raphael S. Soriano.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/modern-maverick/.

Citation Chicago: Erganian, Leslie J. “Modern Maverick: Raphael S. Soriano.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/modern-maverick/.

About the Author:

Leslie Erganian is an American artist, designer, and writer. … More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 This reflection, along with many of those that follow, was recounted in “Interview of Raphael Soriano,” conducted by Marlene L. Laskey for the UCLA Center for Oral History, 1985.

2 Autobiography [unfinished, unpublished] in the Soriano Archive, Archives-Special Collections, College of Environmental Design, California Polytechnic University, Pomona (1970 – 1988).

3 Interview of Richard J. Chilinsky, conducted by Wolfgang Wagener, PhD (1998).

4 Interview of Julius Shulman, conducted by Wolfgang Wagener, PhD, filmed and directed by Leslie Erganian (1998).

5 Interview of Pierre Koenig, conducted by Wolfgang Wagener, PhD, recorded by Leslie Erganian (1998).

Additional information from:

Angel, Marc D. The Jews of Rhodes: The History of a Sephardic Community. New York: Sepher-Hermon Press, 1998.

McCoy, Esther. The Second Generation. Salt Lake City, Utah. Peregrine Smith Books, 1984.

Shulman, Julius. Julius Shulman, Architecture and its Photography. New York: Taschen, 1998.

Wagener, Wolfgang. Raphael Soriano. New York: Phaidon, 2002.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.