by Regine Basha

Featuring video clips and still images from Los Angeles-based home movies excerpted from “Tuning Baghdad,” a narrative archive of Iraqi Jewry in the diaspora as seen through the music, the parties, and the food.

I spent my formative years, from the ages of 8 to 18 years of age (1978–1998) growing up in Los Angeles. My family moved there after 8 years of living in Montreal, and before that 20 years spent in Israel – and before that years, or centuries, spent in Iraq.

The only reason I know the Iraqi song “Fog il Nahal,” which means, either, “I am as happy as the highest date palm tree,” or in other translations “I have a friend above there,” is because it played continuously against the backdrop of my L.A. youth. Though at the time, I couldn’t get further away from the Arabic music my father and his friends played at home and at their parties, it was always “Fog il Nahal” that stuck in my mind like an earworm. Although I could sing it perfectly and whistle the tune, I had no idea what the lyrics were, nor did my parents ever tell me. In fact, Judeo-Arabic was spoken only between them and their Iraqi friends—on the phone, at parties, at the synagogue on Wilshire Boulevard; Hebrew was spoken to my older brothers, who both grew up in Israel; and English was spoken to me. In fact, from around the ages of 4 to 6, I actually believed that Arabic was a language that belonged to adults. I was completely floored when I first heard a young child speak Arabic—ironically, this happened when we visited Israel, and I saw Palestinian children for the first time. Somehow this Arabic got absorbed into my brain in the same department as music and other abstract sounds–elusive but recall-able.

“Fog il Nahal” was particularly loved by the community because it was, as my mother called it, “a happy tune” not a “wailing” tune in the Arabic repertoire. At the all-night house parties that would rotate from Encino to Beverly Hills, the men seemed to love the sad, wailing tunes. They would sit around on the floor waving their hands and wagging their fingers at the musicians, while most of the women gossiped in the other room and only emerged for the more upbeat tunes. I often slept over in guest bedrooms amid the coats and handbags, lulled to sleep by the twang of the khanoun, the sharp drumbeat of the dumbek, and the deep-belly tones of the oud, which my dad would play. Besides “Fog il Nahal,” other songs that filled the repertoire were by the Egyptian greats Uum Khalthoum and Abdul Wahab, or Lebanese songstress Fairouz, and they repeated abstractly in my head the next day as I attended modern dance class at Beverly Hills High. Layered over the remnants of the Arabic music was my daytime soundtrack of another kind of wailing from punk and new wave: The Police, The Cure, Brian Ferry and Siouxsie and The Banshees. Some of these artists I was into experimented even with “oriental sounds” and then of course there was Ofra Haza from Israel whose Yemenite-pop tunes went global. A lot of my friends at the time were also first generation immigrant kids—Mexican, Filipino, Italian, or Armenian—and we were united in our love of alternative music. My best friend at the time, a budding Latina musician, composed her own 1980s version of Latino-Arabic sounds (she was obsessed with the Arabic music my dad played) that predated so much of what would explode in pop music a decade later. It was as if this music shaped our self-understanding as people with different cultures at home. It was not harmony but the disharmony that felt real and more complicated. Strangely, it only occurred to me sometime after college that this kind of happy/ sad sound—shared by new wave and “oriental music”—shared a dissonant tone. It was all about that quarter-tone that makes music sound slightly off-key or seemingly out of tune (especially to Western ears) that made it interesting.

The history of atonal music is bound up with the history of modernism—related to industry, depersonalization, ideas of progress and social utopia. But was the dissonant quarter-tone used in alternative music of the 1980s meant as an expression of difference? It certainly seemed to represent longing but longing for what? My immigrant friends and I might have heard it subliminally, might have interpreted it as a validation of our otherness, of our melancholy at being misunderstood twice – both at home and in greater Californian culture. In a sense, those of us who fall between cultures—the never-really-modern, never-really-traditional cultures—inhabit this space created by the dissonant tone—the tone that resonates as deceptively off-key or unfinished, and that allows us to choose a constant state of tuning.

At the time, I knew that there must have been a really good reason my parents did not speak their native Arabic dialect outside our home and deftly avoided references in public places to their own countries of birth. These were secrets I did not enjoy; they made our otherness more pronounced, as if something to hide. Looking back, what I did enjoy was the flagrant, full-blown joy at the house parties and joy for life in general. Being diasporic did not stop them from enjoying the place they were in. The social life amongst the Iraqi Jews of that generation, in their prime, was non-stop, and extended worldwide. Los Angeles has a pretty sizable community but larger communities are in Ramat Gan, London, Montreal, New York and they often visited one another for special occasions.

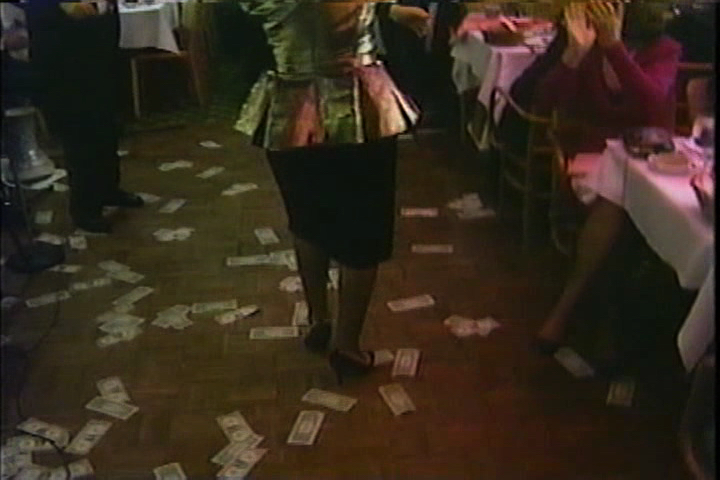

When there weren’t enough families to host those all-night musical house parties, we’d decamp at the popular nightclubs like the Lebanese supper club, “Byblos” on Westwood Boulevard, or “Pips” on Doheny Drive. (Pips wasn’t actually an Arabic club, but the Iraqis liked its plush carpeting, mirrored walls, low-lighting, and disco music.) At Byblos, at least two or three belly dancers would perform with an orchestra throughout the night, and people would throw dollar bills at them and at the musicians. On their breaks, the dance floor would open up for us to dance to DJ favorites like, “That’s the Way (I Like It)” by KC and the Sunshine Band or “Bad Girls” by Donna Summers.

The belly dancers, to my great surprise, were more often American women who had learned to dance in LA, rather than women of Middle Eastern origin. I always wondered how my parents and their friends tolerated this inauthenticity. I later learned that in Middle Eastern cultures, the belly dancer is practically regarded as a prostitute, so no “proper” female would do it in public, as she may shame the family. So when an American girl did it, she was always praised for being a “talented dancer” instead.

In the 1940s, in Iraq at least, even a female singer or entertainer might have been considered loose and compromised. There was only one Jewish Iraqi singer who broke the mold, Salima Pasha, who was and still is exalted amongst Arabic music aficionados, as legendary for her voice. Traditionally, women living in Muslim countries were not supposed to attend musical gatherings in public, let alone sing in public. Although there was nothing of the fanatical Islamic fundamentalism we are seeing today during my parents’ time in Baghdad, the conservative customs were solidly in place, as they were within the Jewish community, when it came to women appearing in public spaces (my grandmother, Regina Basha, who started her own jewelry store in Baghdad was an exception to this rule). I often think back to how liberated the Iraqi women of 1980s Los Angeles must have felt to be dancing to KC and The Sunshine Band at Pip’s.

So much seemed to be revealed at those house parties and through the music. Every so often I’d see a woman who so loved Arabic music that she couldn’t help singing alongside the men. One such family friend—I’ll call her “Laura,” which is the name she chose when she came to the States—sings a mean “Fog il Nahal” herself, when begged to do so. Her family had migrated to California earlier than my parents did, in the 1950s, so the evidence of assimilation into American culture was much more pronounced; the family’s accents were less noticeable, their children were more Americanized, the parents seemed less strict than my own, and they had a dog (traditionally Iraqi Jews grew up with the adopted distaste for having dogs as pets).

Laura was the quintessential hostess for Iraqi parties. She made everyone from every class within the community feel at home. Her home was always open on Saturday mornings for Shabbat breakfast and always available for the night-time gatherings as well. She also arranged for all the music, sometimes bringing in Palestinian or Syrian musicians who could play the instruments and the tunes loved by the Iraqi Jews. No one ever spoke openly of this inter-religious musical arrangement. Families who came from Israel, Indonesia, Iran, India, England, China, whether living in L.A. or in town for a wedding would collect at these parties and catch up on community news. They all seemed to know one another through their last names; The Kassabs, the Sharabanis, the Zakarias, the Dalals, the Kattans, the Masris, the Inis, the Kadooris, the Rejwans, the Khamaras, the Mashaals…. Silman (Shlomo) Basha, my father, knew everyone, and had a particular knack for tracing each families’ far-flung trajectory through the world.

Loads of live recordings of these house parties on cassette tape and VHS tapes filled my father’s bathroom cabinet. My own teenage cassette collection from this time has nothing on his. The cassette dubbing wasn’t only about capturing the music but just as much the calling out, teasing, and jokes from the live audience. They were traded and presented as gifts to friends and enthusiasts abroad in a network that, ultimately, contains the social code for holding these people together. I could say that the parties were not necessarily about nostalgia but might have been more like a re-enactment or a re-activation of their time in Baghdad. It was as if this secret musical citizenship washed over the landscapes of time, place and political, geographical lines. Repeated again and again in different homes—the same songs, the same food, the same kind of gossip and the same kind of guests—this was the ever-present internal life of the party, where the music of 1940s and 1950s Iraq and Egypt played on in pockets of Beverly Hills, Westwood, and Encino. I had often wondered if Iraqis back in Iraq were also still listening to this same repertoire at their own music-filled get-togethers known as chalghis.

Loads of live recordings of these house parties on cassette tape and VHS tapes filled my father’s bathroom cabinet. My own teenage cassette collection from this time has nothing on his. The cassette dubbing wasn’t only about capturing the music but just as much the calling out, teasing, and jokes from the live audience. They were traded and presented as gifts to friends and enthusiasts abroad in a network that, ultimately, contains the social code for holding these people together. I could say that the parties were not necessarily about nostalgia but might have been more like a re-enactment or a re-activation of their time in Baghdad. It was as if this secret musical citizenship washed over the landscapes of time, place and political, geographical lines. Repeated again and again in different homes—the same songs, the same food, the same kind of gossip and the same kind of guests—this was the ever-present internal life of the party, where the music of 1940s and 1950s Iraq and Egypt played on in pockets of Beverly Hills, Westwood, and Encino. I had often wondered if Iraqis back in Iraq were also still listening to this same repertoire at their own music-filled get-togethers known as chalghis.

As my curiosity about our identification with Arabic music grew over time, I decided to research the history of the “chalghi.” It turns out that there was indeed a Jewish folk ensemble begun in the 1920s called “Chalghi Baghdad” complete with a ney (kind of flute), dumbek (drum), joza (a one-stringed violin), and oud, that was invited to represent Iraq at the 1932 Cairo International Music Convention–the first music industry event of its kind in the Middle East. At that time, Jewish musicians were not separated from Iraqi culture, hence Chalghi Baghdad would play traditional Iraqi Maqam, which was never considered “Jewish music” but music for all of Iraq. For reasons that had to do with social mores at that time, the singers were often Muslim and the Jews tended to be the musicians/instrumentalists of Iraq—so much so that music naturally ceased on the radio and in the streets of Baghdad on Yom Kippur. Chalghi Baghdad was known to play in public spaces and also in house parties usually formed to honor a marriage, bar mitzvah, or a briss in the Jewish neighborhoods of Baghdad and Basra. Another arena where Jewish musicians played a role in shaping the culture was on the radio.

In the early 1930s, the Iraqi National Radio station was founded by the Jewish brothers Salah and Daoud Al-Kuwaiti and soon became a productive place for new compositions and collaborations, with musicians such as Daoud Akram, Salim Daood or Salima Pasha. A Jewish school for blind children, called Dar Mua’sat Al-Imyan happened to foster some of the best musicians of the time, and many of them became the teachers of the subsequent generation of musicians throughout Iraq.

This led to the writing of many new modern compositions modeled after the popular Egyptian compositions at the time with songs based on longing, love and loss (as Egypt led the way for Modern Arabic music throughout the whole Middle East). In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the “force majeure” (mass departure and airlift of the Iraqi Jews) of this population led to a palpably-felt vacuum in the music scene of Iraq. Many of the renowned musicians landed in Israel–The Kuwaiti brothers and virtuosic musicians such as the blind khanoun player Abraham Salman, or the singer Filfel Gourgi–all of whom ended up living modestly and mostly out of the spotlight in an Iraqi Jewish suburb of Ramat Gan performing mostly as favors to friends in the local community. Salman was a beloved child prodigy in Iraq and did have a brief stint performing shortly after arriving as part of the program “Kol Israel” (a televised “Oriental” orchestral broadcast à la Lawrence Welk). When I interviewed him for my website Tuning Baghdad, his wife told me of the continued following throughout the Middle East, and when efforts to transport him back for a concert proved futile. Earnestly, I asked Salman if he could explain the Iraqi maqam to me, in layman terms perhaps. He reluctantly responded in Arabic by first asking where I lived. When I stated, “America,” he simply said, “Oh . . . that’s too far.”

It appears that in other Mizrahi cultures such as Moroccan, Yemenite, Syrian, there is a resurgence of interest amongst a new generation of music enthusiasts who are seeking out this modern chapter in Mizrahi Jewish history. Since Saddam Hussein had actively erased the Jewish contribution to Iraqi culture, there is also a surprising newly growing interest of this history on the part of other Iraqis and present-day Iraqi musicians, which we are finding in films like On The Banks of the Tigris, directed by Marsha Emerman, with present day Iraqi maqam singer Hamid Al-Saadi or for instance musician Amir El-Saffar who recognize the valuable contributions the Iraqi Jews had to the country’s musical history. In Israel, artists such as Yair Dalal and Dudu Tassa, second and third generation Iraqi Jewish musicians, have revived many of the older songs and are touring the world music circuit with their own interpretations of them.

How ironic is it then that in the salons of Encino, or the living rooms of Beverly Hills, we are more likely to hear the in-tact sounds of Iraq’s beloved cultural treasure–Chalghi Baghdad, than we might hear in Iraq itself. This, resonating from one of the first waves of Iraq’s refugees, the Jews–and quite literally the last bastion of cosmopolitanism in the city of Baghdad. If there could be a sound for that condition, it would definitely ring atonally.

To listen to more from Regine Basha, check out her “Tuning Baghdad” radio show.

Citation MLA: Basha, Regine. “Life of the Party.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/life-of-the-party/.

Citation Chicago: Basha, Regine. “Life of the Party.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/life-of-the-party/.

About the Author:

Regine Basha is an art curator, writer, and educator in New York More

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.