The early 1930s were a time of considerable development for the Rhodesli (Rhodian) faction of Sephardim in Los Angeles. Operating independently from other Sephardic entities since 1917, the Peace and Progress Society (La Sosiedad Paz i Progreso) of the Rhodeslis established the physical, spiritual, and linguistic organization of its community, laying the groundwork for generations to come. In the years leading up to the 1935 founding of their own synagogue on 55th Street and Hoover Avenue, the Peace and Progress Society documented their intra-communal happenings and inter-communal relations in a short-lived periodical titled El Mesajero (The Messenger). While this publication addressed concerns related to the unification and dissolution of Sephardic institutions and traditions, the use of Ladino and discussions surrounding its use reveal how Sephardim utilized language to further negotiate their identity as Sephardim, Jews, and Americans.

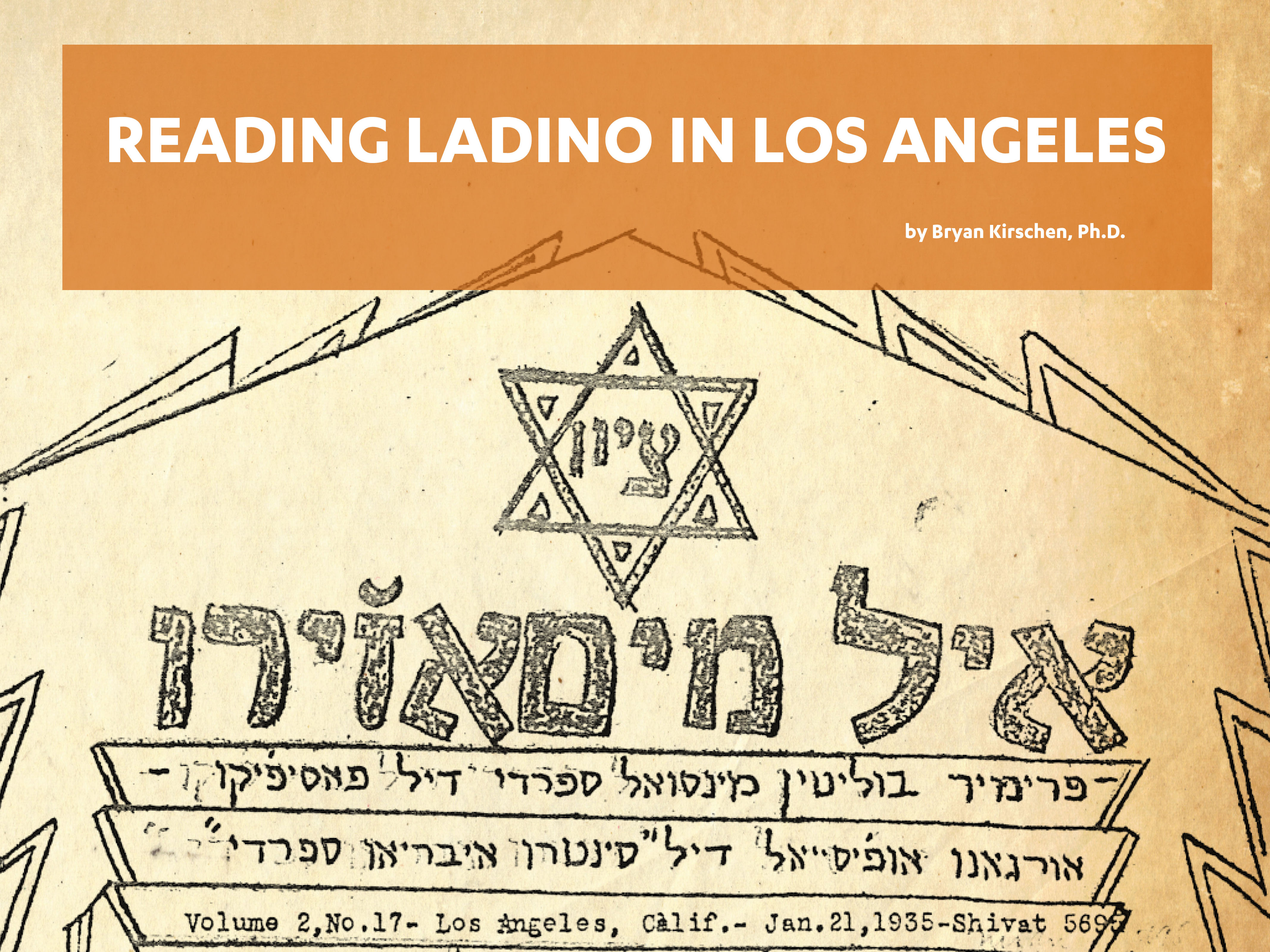

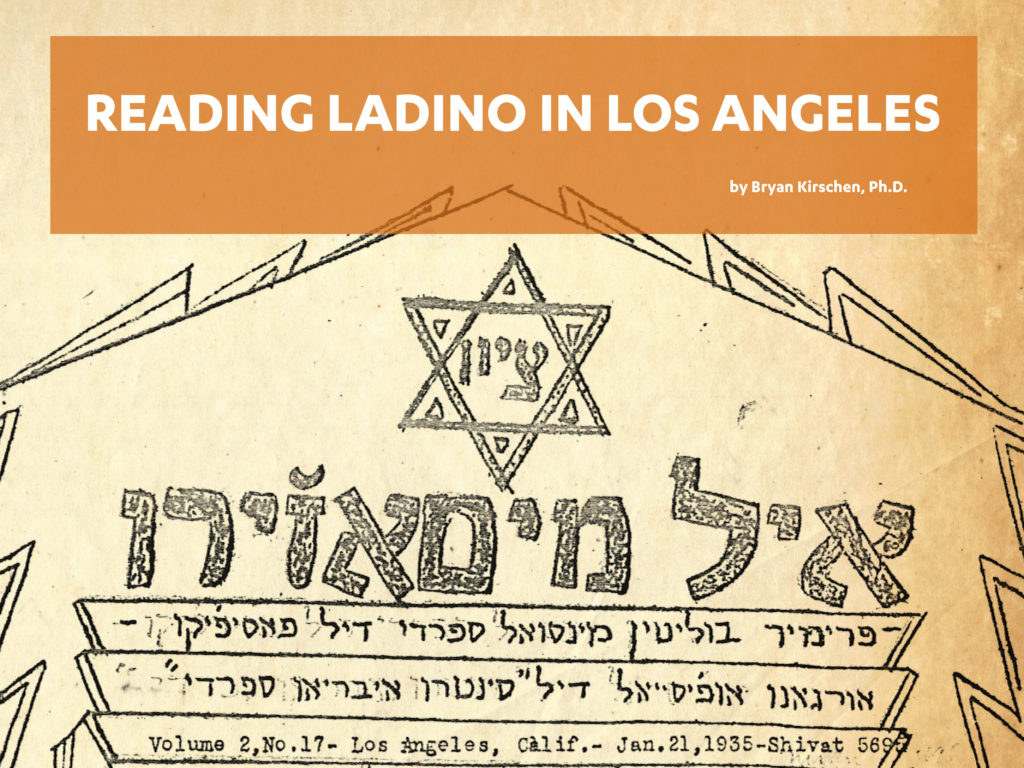

El Mesajero was printed monthly from September 1933 until July 1935, resulting in at least nineteen unique numbers. The name of the paper itself mirrors that of a periodical published on the Island of Rhodes, Il Messagero di Rodi (“The Messenger of Rhodes”), printed in Italian as early as 1916. As the official publication of the Peace and Progress Society, El Mesajero became the first Sephardic bulletin of the Pacific, a statement which often appeared in the paper’s masthead. While twenty different Ladino-language periodicals were published in New York throughout the first half of the twentieth century, El Mesajero provides a rare look into Sephardic life in Los Angeles at a pivotal time in the community’s development.1

Contributors to El Mesajero wrote about local, national, and international concerns related to Jews, as well as more general columns regarding everyday matters, such as those centered around the well-being and health of their readers. We also learn of the social organization of the Sephardic community from the renaming of the Peace and Progress Society to that of the Sephardic Hebrew Center (El Sentro Ebreo Sefaradi) to the activities of groups such as the Ladies Auxiliary, the Maccabean Knights, the Maccabean Daughters, the community’s Talmud Torah school, as well as the Bikur Holim association for the elderly.

Among the first generation of Rhodeslis, Ladino would serve as their primary vehicle of communication. As with most immigrant groups in the United States, however, transmitting a language other than English to subsequent generations can prove challenging; Ladino would be no exception. The remainder of this piece serves to explore the fragile state of Ladino in Los Angeles during the first half of the 1930s, by considering how contributors to El Mesajero utilized, represented, and discussed the language.

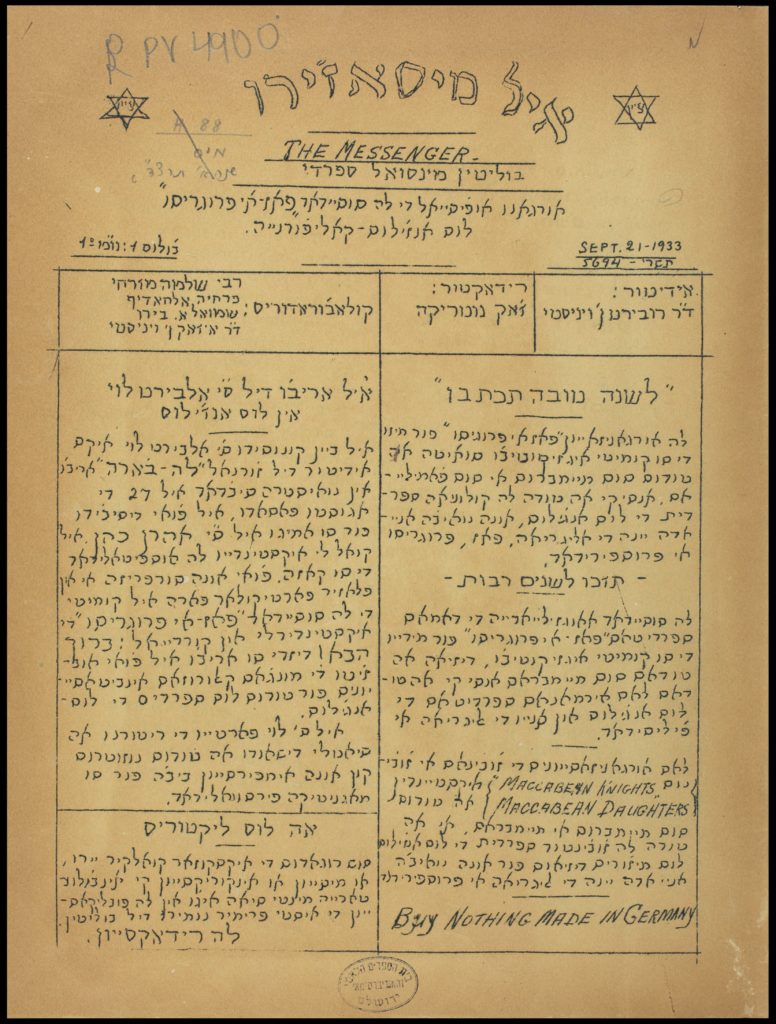

In the initial months following the inception of El Mesajero, nearly all entries were written and copied by hand in Ladino in Rashi characters. Exceptions to this included the use of Meruba characters, which appeared in either the masthead (such as the title) or in certain headlines throughout the paper. The use of a Hebrew-based alphabet (Meruba or Rashi) to orthographically represent Ladino was a common practice across Ladino-language newspapers in the United States and abroad. This form of transcription is known as aljamia(do). Aside from the use of Ladino in El Mesajero, Hebrew, in Meruba characters, was used sporadically throughout headlines, (religious) phrases, and loanwords. Linguistically, the implementation of Hebrew loanwords into a mostly otherwise Spanish-based sentences resulted in clear orthographic differences. That is, while all vowels are represented in the transcription for words in Ladino, this is not the case for those that come from Hebrew. Though it is not possible to ascertain the bi/multilingual proficiencies of the contributors to the paper, the use of these scripts demonstrates metalinguistic awareness at the least. Other than Ladino and occasional Hebrew, the only other language to appear in the initial issues was that of English. As seen in the first number of the paper, the only instances of English were to provide the translation of the title of the paper, the date of publication, proper nouns referring to social groups, and the regularly displayed counsel to “Buy Nothing Made in Germany.”

A major turning point in the publication of El Mesajero occurred in the December 1933 edition of the paper, only months after its launch. In this issue, Samuel Berro published a piece titled “Why ‘The Messenger’ Should Also Publish Articles in English” which notes that for the past two decades, Sephardim have been doing their best to assimilate to their greater surroundings. He continues to assert that Sephardim have overlooked the importance of speaking English, which he believed to be necessary to be a good American citizen. Berro further laments that “contrary to our brethren, the Eskenazim (sic) who have made remarkable progress toward the culture and mastery of the English language, we Sephardic Jews, have contributed little to that valuable asset.” In order to foster the advancement of Sephardim—especially among younger generations of men and women now attending public schools and colleges—the paper would begin to regularly include articles in English. Aside from this article being the first to appear in English in the paper, it is also the first article to be typed.

The January 1934 edition of El Mesajero became the first paper fully typed, which included Ladino articles appearing in Meruba typeface and an ever-increasing number of articles in English in a Latin character typeface. Rashi characters would no longer be used in this paper. The implementation of Meruba characters alongside or in place of Rashi characters was common in other newspapers appearing in Ladino, especially in New York City.

Months after the shift from Rashi to Meruba characters, and only a year after the launch of El Mesajero, the paper would change again in regard to the way it orthographically represented Ladino. As of September 1934, El Mesajero began to publish articles in Ladino in Latin characters. In subsequent months, readers would find some articles printed in Ladino in Latin characters and others in Meruba characters. It was not until the April 1935 edition of the paper that we find the appearance of Ladino only in Latin characters, apart from articles in English as well. This number of El Mesajero is thought to be the final issue of the paper, but another number was published in July 1935.2

Like the preceding issue, this number included Ladino only in Latin characters, with final pages in English. Unlike the preceding issue, or any prior issue for that matter, Ladino in Latin characters was also used in the masthead of the paper. This was the first time that the title of the paper did not appear in Meruba characters, despite numerous iterations of the masthead over the span of the paper. Additionally, this was the first time that the word “Zion” did not appear inside of the Star of David in the masthead, replaced with S.H.C. (Sephardic Hebrew Center).

While the editorial board of El Mesajero focused their paper on Los Angeles, they were in contact with other Sephardic communities throughout the country, particularly those of New York City and Seattle. Showing no sign of regret for including English in their columns, editors of El Mesajero would comment on how a similar trend was taking place within one of New York City’s more prominent Ladino newspapers, La Vara. In August 1934, the editorial board of El Mesajero extended congratulatory remarks to La Vara for “su loavle inisiativa de entrodusir una seksion ingleza en sus kolunas por el benifisio de nuestra joventud sefaradita” (“its laudable initiative of introducing a section in English into its columns for the benefit of our Sephardic youth”). A month later, editors then suggested that Sephardic communities nationwide commend La Vara for introducing articles in English in its columns. They asserted that the inclusion of English represented “a step forward toward the preservation of many of our religious and other institutions in the future.” Of course, what they most likely did not consider at that time was that all shifts toward English would serve as a catalyst for the endangerment of their mother tongue in the years—and generations—to follow. The January 1935 edition of the paper, in fact, was the first to include news in English on its front page.

While the July 1935 number is the last known issue to be published by El Mesajero in Los Angeles, it is not clear whether or not the editors of the paper foresaw its closure. This number included an article titled “Y Porque Nuestra Seccion Espanola,” (And Why Our Spanish Section?), which highlighted the importance of (Judeo-)Spanish to their readership, noting that ever since the appearance of the newspaper in “Ladino characters,” there has been a steady stream of disapproval, especially among the youth. The editor defends the use of Ladino (“Spanish”) in the paper since, although many are able to read English, “no llegan a intender los escritos asi facilmente como lo pueden en espanol sus lengua maternal” (“they are unable to understand writings as easily [in English] as they are able to in their own maternal language, Spanish [Ladino]”). The piece finishes with an envisioned objective of working toward the betterment of the publication, “hasta crearlo en un periodico regular, bien establicido en nuestro estado” (“until creating a regular, well-established newspaper in our state”).

Throughout the pages of El Mesajero, readers witness language contact between Ladino and English. If contributors to the paper weren’t writing entirely in English, they utilized the language as needed throughout their Ladino. Whether in Rashi, Meruba, or Latin characters, words from English are observed, which was also common in Ladino production from New York around this time.3 The ways in which writers included such borrowings are diverse. Though sometimes borrowed words are placed within quotation marks to mark the non-Ladino element, words are often adapted to the morphological and phonological construct of Ladino. Some examples that appear throughout the paper include: picnics, card partis, mitings, boicots, bar, clubes, trustis. Of course, such borrowings, often associated with cultural and organizational practices, are common in other languages as well.

Aside from minimal but notable contact between Ladino and English, there is also something to be said regarding contact between Ladino and Spanish. While the language of the Sephardim developed under different historical and linguistic circumstances than did the Spanish varieties that developed in Spain and throughout the Americas in the centuries following 1492, there is considerable overlap between them. That noted, there are also a gamut of lexical items that differentiate Ladino from (other varieties of) Spanish. However, in El Mesasjero, we often find words of both stock. Examples include meldar and leer “to read,” merkar and komprar “to buy,” lavorar and trabajar “to work,” and la fragua and el edificio “the building,” with the first word in each grouping pertaining to Ladino and the latter more often associated with other varieties of Spanish.

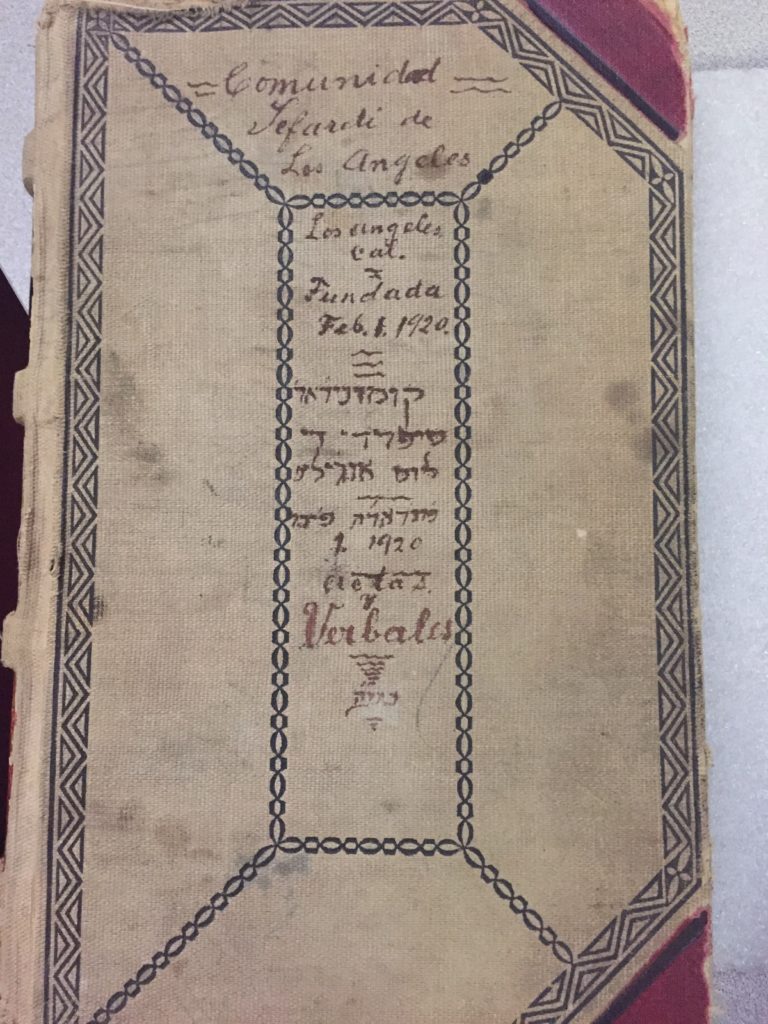

Contact between Ladino and Spanish became most visible one year after the paper’s debut, when El Mesajero began to include articles in Ladino in Latin characters. Contributors to the paper would vary in the ways in which they would orthographically represent their Ladino. Though not always, Ladino began to mirror the orthographic norms of Spanish. In some cases, writers placed accent marks over their words in an attempt to indicate where stress fell, which is something that had not been done before when using a Hebrew-based alphabet to orthographically represent Ladino. As early as 1920, the Turkish faction of the Sephardic community of Los Angeles, known as La Comunidad, had already chosen Spanish over Ladino, for the minutes from this year noted that (Castilian) Spanish would be their official language.4

The ephemeral lifespan of El Mesajero illustrates the constant negotiation of how Ladino was used in the paper as well as community-based ideologies that brought about related discussions and implementation. In this regard, Los Angeles was very similar to other Sephardic communities in the nation and abroad, which regularly wrote about matters concerning language.5 While the editors of the paper believed assimilation to be a positive by-product of living alongside non-Sephardim, they may not have fully recognized the linguistic ramifications of encouraging their brethren to distance themselves from Ladino. And although we can still hear remnants of Ladino throughout Los Angeles to this day, El Mesajero provides a glimpse into the shifting structure of the language and ideology of its community from nearly a century ago.

Citation MLA: Kirschen, Bryan. “Reading Ladino in Los Angeles.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/reading-ladino-in-los-angeles/.

Citation Chicago: Kirschen, Bryan. “Reading Ladino in Los Angeles.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/reading-ladino-in-los-angeles/.

About the Author:

Bryan Kirschen is an Assistant Professor in the Romance Languages and Literatures Department at SUNY Binghamton…More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Aviva Ben-Ur, “The Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) Press in the United States, 1910-1948,” in Multilingual America: Transnationalism, Ethnicity, and the Languages of American Literature, ed. Werner Sollors (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 64-78.

2 Paloma Díaz-Mas and María Sánchez Pérez, “La comunidad sefardí de Los Ángeles (California) y su periódico ‘El Mesajero’,” eHumanista 20 (2012): 153-71.

3 Bryan Kirschen, “Language Ideologies and Hegemonic Factors Imposed upon Judeo-Spanish Speaking Communities,” Mester 42, no. 1 (2013): 25-38.

4 Julia Phillips Cohen and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, eds., Sephardi Lives: A Documentary History, 1700-1950 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014), 354.

5 Yvette Bürki and Rosa Sánchez, “On verbal hygiene and linguistic mavens: Language ideologies in the Ottoman and New York Judeo-Spanish press,” in Jewish Journalism and Press in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, ed. R. Bali (Istanbul: Libra, 2016), 3-74.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.