Zohra El Fassia (1905-1994) was among the most important Moroccan vocalists of the 1950s. Like so many high-profile Arabophone recording artists and performers across the Maghrib (Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia), El Fassia was Jewish. In vogue and in demand in the Moroccan cultural capital of Casablanca, her sudden departure for Israel in 1962 would cast her life and career in a dramatic new direction. If she lived large−or at least lavishly−in French colonial and then independent Morocco, she found herself impoverished in Israel, relegated to an impossibly small Jewish Agency apartment in the coastal city of Ashkelon. Back home, she had been supported by her fans, which included King Mohamed V, legions of Jewish and Muslim concertgoers, and those with the means to hire her for private celebrations. But in her new homeland, her numerically diminished base could hardly sustain her or her music career. Besides, Hebrew was the musical idiom of the Jewish state, not Arabic. After shining in Morocco for decades, Zohra El Fassia’s star in Israel would fade tragically.

In 1976, however, Zohra El Fassia gained the spotlight once more, at least for a moment. That year, the Algerian-born Israeli poet Erez Bitton seared a vision of Zohra El Fassia into some segments of Israeli consciousness with his nearly elegiac, “Zohra El Fassia’s Song.” In constructing the Hebrew-language poem, he leaned heavily on memory. There were no archives to speak of at the time. Its first verse, in fact, hinges on the reader either remembering or at least conjuring the Jewish diva as she once was. With a whiff of the folkloric “they,” Bitton’s poem reads:

Singer at Muhammad the Fifth’s court in Rabat, Morocco

They say when she sang

Soldiers fought with knives

To clear a path through the crowd

To reach the hem of her skirt

To kiss the tips of her toes

To leave her a piece of silver as a sign of thanksZohra El Fassia1

That memory of the past stood in direct contrast to her present as articulated spoken-word style in the verse that followed.

Now you can find her

In Ashkelon

Antiquities 3

By the welfare office the smell

Of leftover sardine cans on a wobbly three-legged table

The stunning royal carpets stained on the Jewish Agency cot

Spending hours in a bathrobe

In front of the mirror

With cheap make-up–

When she says

Muhammad the Fifth

Apple of our eyes

You don’t really get it at first

Zohra El Fassia’s voice is hoarse

Her heart is clear

Her eyes are full of love

Zohra El Fassia

Decades after the publication of Bitton’s poem, interest in Zohra El Fassia has surged and not just in Israel. That awareness owes to the enduring quality and power of “Zohra El Fassia’s Song,” the increased availability of her recordings on YouTube, and the desire by young Jewish and Muslim musicians to reinscribe Zohra El Fassia into the historical record. Indeed, narrating Zohra El Fassia’s story–in concert or otherwise–acts to doubly remind. On the one hand, Zohra El Fassia serves as a reminder of the Jewish-Muslim music-making past in the Maghrib. At the same time, her fate underlines the discrimination faced by Mizrahim in Israel while also acknowledging the ways in which North African and Middle Eastern Jews resisted Ashkenazi cultural hegemony through song and language. In the last few years, then, Israeli artists like Neta Elkayam and Amit Hai Cohen and their counterparts in Morocco like Fayçal Azizi have reimagined El Fassia’s repertoire before large, enthusiastic audiences in their respective home countries and around the globe.

Morocco-Israel–France–City of Angels (and Chance Encounters)

At the height of Zohra El Fassia’s career in Morocco in the mid-twentieth century, her family sought out new lives in France, Israel, and eventually the United States. In either 1962 or perhaps 1963, Zohra El Fassia made the fateful decision to join those who had settled in Israel. In fact, while 1962 is the date most associated with her departure and arrival, an agenda book in her archive gives pause. In early 1963, Zohra El Fassia had been booked for two engagements in the Moroccan capital of Rabat: the Assouline anniversary party and the Luski marriage. Unfortunately, whether she ever performed for them remains unclear. Regardless, by the time Zohra El Fassia had settled into her new home in Ashkelon, Israel, her daughter Henriette found herself in the United States after a stint in Paris. In Chicago, she started going by the name of Monette. Soon she landed in Los Angeles. The rest is pure Hollywood.

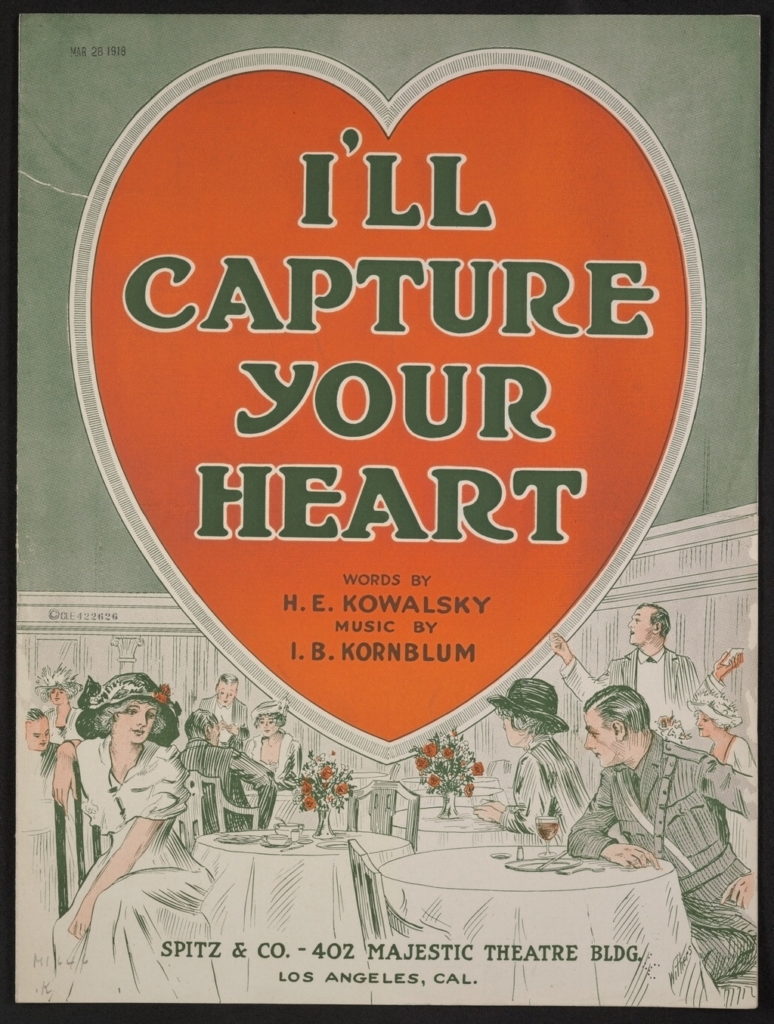

In 1969, Monette, daughter of Zohra El Fassia, met her future husband David Kornblum, son of I.B. Kornblum. David, like his father, knew music. He had been raised on it. His father, Isidore Benjamin “I.B.” Kornblum, was born in 1895 in St. Louis, Missouri. As a child, I.B.’s family moved to Los Angeles and began developing land in the South Bay. Kornblum Avenue, which straddles the 105 and 405 in Hawthorne, stands as a testament to that legacy. The same is true for Kornblum School, which sits at the northern edge of the family’s eponymously named avenue.

I.B. Kornblum, like so many others of his generation, got his start with music when he received a piano for his Bar Mitzvah. As a student at Los Angeles High School, he wrote his first musical. In 1915, while at UC Berkeley, he proceeded to pen the appropriately named “Fight ’em” fight song, which was performed by the Cal marching band during the “Big Game” against the University of Washington that year and for the next several.2 While attending Berkeley Law, he began moonlighting on the piano at the Orpheum Theater in Oakland, often accompanied, musically and otherwise, by silent film star and singer Carmel Myers, who was to be his first wife. In Oakland, I.B. was discovered by Tin Pan Alley and Broadway composer Joseph Howard, who brought him to New York in 1921. After a short run on Broadway with shows like “Blue Eyes” and “Twinkle Toes,” I.B returned to Los Angeles to practice entertainment law. He also became legal counsel to some of the most important artist unions in the world, among them the organization that would eventually become the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA).

David Kornblum, born in 1930, very much followed in his father’s footsteps. He too attended law school, first at the University of Arizona and then at UCLA. Upon graduation in the 1950s, he went to work for the William Morris Agency, the premier American talent agency for most of the twentieth century. After a few years at William Morris, David went into business with his father before eventually branching out on his own. In the 1960s, he became a top entertainment lawyer with his own firm.

In 1969, Monette connected with David Kornblum. She needed a lawyer. An affair between Oliver Berliner, the son of recording pioneer Emil Berliner, and the Hollywood actress Choo Choo Collins had ended badly. Berliner began to sue everyone around Collins, including her secretary Monette. She set up an appointment with David. The meeting turned into dinner. From Beverly Hills, the two headed out for a meal at the now iconic Casa Vega in the San Fernando Valley. From that moment on, the two were inseparable. Monette sent a telegram to her mother in Israel announcing their engagement.

Zohra El Fassia in Los Angeles

Zohra El Fassia came to Los Angeles for the first time in the early 1970s to visit her daughter and son-in-law. During that visit, the Kornblums took her to an Egyptian restaurant on Vermont Avenue. It seems there must have been a good number of Moroccans among the diners as Zohra El Fassia was soon recognized and then ushered to the upstairs balcony to perform. She did so majestically. On another occasion, in the late 1970s, at the famed Dar Maghreb restaurant on Sunset Boulevard, David patched in his mother-in-law from Israel via phone in order to sing for unsuspecting customers. Between picking up the phone and the start of her tele-concert, those at the restaurant waited with baited breath. Apparently, El Fassia insisted on putting her makeup on before launching into song.

Zohra El Fassia’s initial visit to Los Angeles coincided with the growth of the organized Moroccan Jewish diaspora in Southern California, a community that David and Monette Kornblum helped to establish. David, for example, wrote the original 1974 legal articles of incorporation for Em Habanim in Valley Village, Los Angeles’ first Moroccan synagogue. Between 1987 and 2009, Haim Louk, a leading practitioner of the Hebrew variant of the classical Andalusian musical repertoire and current fixture of the sacred music circuit operating between Morocco and Israel, was installed as Em Habanim’s spiritual leader and rabbi.

David would also go on to serve as in-house counsel for the many Moroccan Jews involved in the Los Angeles-based fashion industry. Among his clients were Jeff Hamilton (né Jeff Bohbot), who served as the Creative Director for GUESS, which was, of course, founded by another Moroccan Jew: Georges Marciano. Monette’s contribution was significant as well. Monette, one of the Westside’s most important real estate agent’s at the time, curated some of Los Angeles’ first Mimouna celebrations, the Moroccan Jewish holiday which marks the end of Passover. Given the Kornblums network, these gatherings were no doubt an extravagant and fashionable affair.

Just as the Kornblum’s helped establish the Moroccan Jewish community’s future in Los Angeles, they also worked to preserve an important piece of its history. On November 4, 1994, Zohra El Fassia died in a nursing home in Israel. Her daughter was there by her side. After the funeral, Monette returned to Los Angeles. She carried with her two boxes that were no doubt once part of a much larger archive and that had since disappeared. The two boxes were deposited at the Kornblum home and had sat there for decades. Incredibly, Los Angeles’ climate, capacity for space, and anonymity offered Zohra El Fassia’s archive protection.

It was in Los Angeles that Monette assumed her mother’s legacy might be preserved. She was more than prophetic in this regard. As Monette spent her final days convalescing in the upper floor of the Kornblum home, I–then a graduate student at UCLA–worked with David downstairs to inventory those two boxes. There, in the Hollywood Hills, Zohra El Fassia’s biography came into focus, Moroccan Jewish Los Angles revealed itself, and two children of musicians lived their lives together–bridging improbable worlds as only the City of Angels can.

Zohra El Fassia: Toward a Biography Buried in Boxes

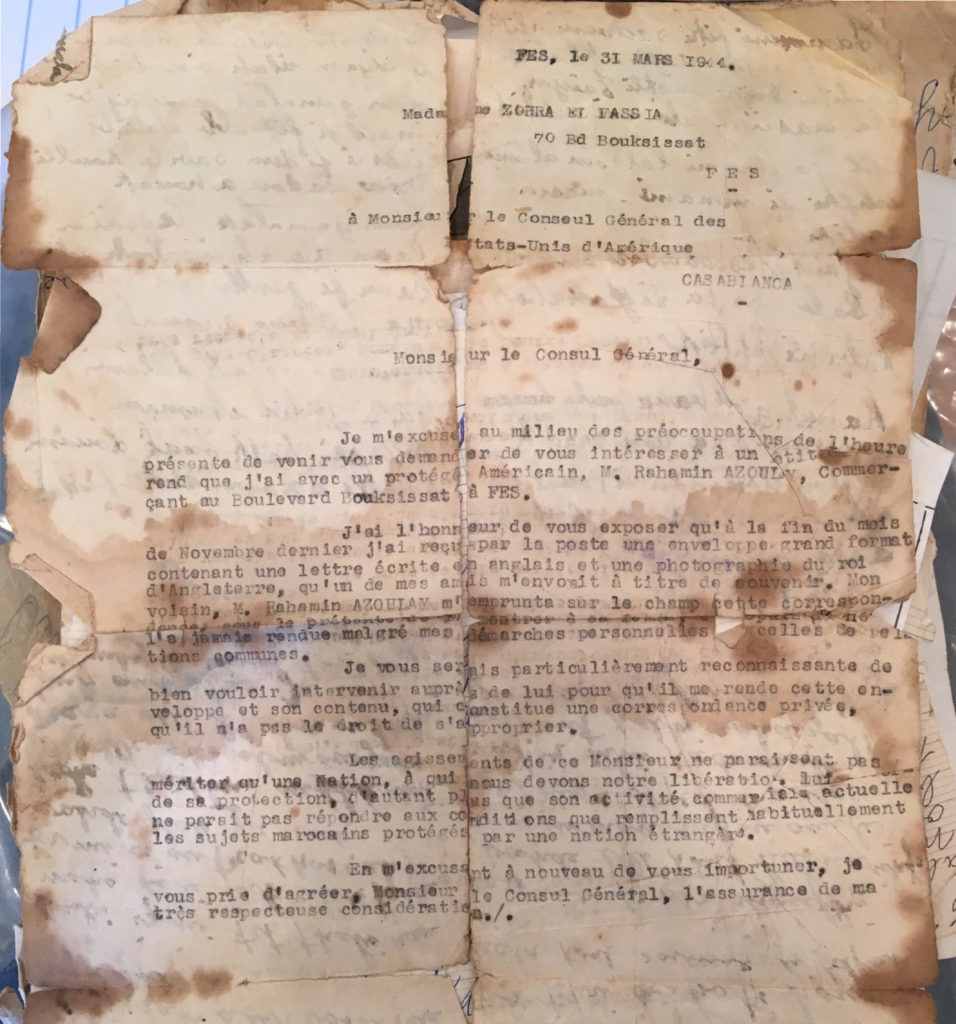

Zohra El Fassia was born Zohra Hamou in Sefrou, Morocco in 1905. As a child, she moved from Sefrou to the former imperial capital of Fez, from whence she would eventually adopt her stage name of “El Fassia” (or, “the woman from Fez”). By the time she started recording 78 rpm records for the Polyphon label in the mid-to-late 1930s, she already bore the title of “cheikha,” of master musician. The thirty-something year old artist lived in Fez at least until the mid-1940s. There she would experience antisemitic Vichy rule in the course of the Second World War. On March 31, 1944, nearly a year and a half since the liberation of Morocco in the course of Operation Torch, she sent a letter to the American Consul in Casablanca about the theft of her mail by her neighbor Rahamin Azoulay, an American protégé. She signed it with her stage name to give the message added weight. But why go through all that trouble over a stolen parcel? Well, Azoulay had taken a package sent to her from England, which contained a large photo of King George VI, a “souvenir,” as she called it, of Allied victory. “The actions of this gentleman,” El Fassia wrote of Azoulay, “do not befit a nation to whom we owe our liberation.” Having lived Vichy’s anti-Jewish race laws in Morocco, El Fassia remained grateful to her American liberators.

In due time, Zohra El Fassia moved to Casablanca, not far from the cultural capital’s vaunted Cinéma Vox. The modern venue, one of the largest in North Africa, saw talent from across the Maghrib perform there, including El Fassia, as well as legendary Egyptian musicians like Farid El Atrache. While the salvaged documents in El Fassia’s archive are sometimes thin, what emerges after careful review is something akin to a sonic geniza. For example, on the back of that 1944 letter to the American Consul–which had been returned to sender–were song lyrics, exquisitely scrawled in her own hand. That piece of paper was then folded and tucked into her caftan for use during a performance. The two boxes abound with similar such musical palimpsests from an evidently demanding concert schedule.

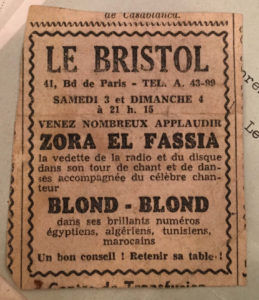

Despite frequent appearances in venues ranging from the large Cinéma Vox to the more intimate Le Bristol, the archive makes clear that the public needed to plan if they hoped to catch Zohra El Fassia live. Demand was high. One 1950s newspaper clipping called on fans to “reserve their table” in advance of an upcoming concert featuring Zohra El Fassia and the Algerian Jewish recording artist Blond-Blond (who was often compared to French entertainer Maurice Chevalier). Beyond the concert scene, El Fassia was a frequent contributor to Radio Maroc toward the end of the French colonial period and through Moroccan independence in 1956. What did she sing in those various spaces? Far more than we previously thought. There was, for example, the patriotic and nationalist. She was as devoted to Sultan Muhammad V and Crown Prince Hassan II as her patrons were to her. She also masterfully executed malḥun, a colloquial repertoire closely associated with classical Arabo-Andalusian music, which itself traced its origins to medieval Islamic Spain. But so too do we now know that she sang popular Moroccan, Libyan, and Egyptian music, including titles from the Golden Age of Arab cinema. Any and all of this music featured at her nearly weekly wedding performances, which provided a steady stream of income for her. But she was not just hardworking. She hustled. The two boxes deposited in Los Angeles reveal that Zohra El Fassia pursued her royalty statements from her 78 rpm records cut with Pathé, Polyphon, and Philips with gusto for decades to come.

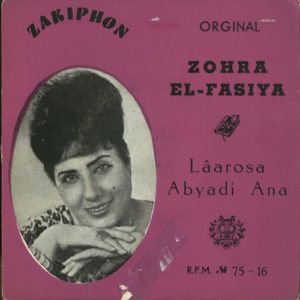

As some members of the Moroccan Jewish community, including her daughter Monette, began to flourish in Los Angeles, Zohra El Fassia did the best she could to maintain her illustrious past while living in government housing in Ashkelon. To be sure, she was celebrated by her Moroccan compatriots, whose icon was now once again among them. Soon after her arrival in Israel in the 1960s, she relaunched her recording career with Zakiphon, the Jaffa-based label founded by the Morocco émigré Raphaël Azoulay and dutifully shepherded through until the present by his sons. Zakiphon, along with its related label Koliphone, took on the monumental task of capturing to disc the voices of all those artists that the mainstream Israeli outfits Makolit and Hed-Arzi would not touch: namely those from the Middle East and North African who persisted in singing in Arabic in the Jewish state. But even Moroccan audiences in Israel clamoring for the Arabophone sounds of the Maghrib wanted something new and different. Others emerged as Zohra El Fassia was forced–somewhat–from center stage. When she did headline, it was in smaller venues of far less prestige. Café Noga in Jaffa was hardly Cinéma Vox in Casablanca.

Shortly after she landed in Israel, Zohra El Fassia received some local press and attention. This is attested to by her archive. In 1965, for example, Le Comité de Coordination des Unions d’Originaires d’Afrique du Nord En Israel organized an exhibit on North African Jews, their culture, and “their contribution to Israel’s development.” The exhibit, showcased at the International Cultural Center for Youth (ICCY) in Jerusalem, opened on January 13, 1965, and was presided over by Zalman Shazar, the President of Israel. Zohra El Fassia was there but not so much as a guest. On the first floor of the ICCY, in “a reproduction of the salon of a well-to-do Moroccan family,” the former star sat on a low sofa placed atop carpets, surrounded by silver platters and samovars, all of which she had personally provided. Who knows how long she remained there in that reified position. Tragically, Zohra El Fassia was being reduced to a museum piece while still in her prime.

In addition to filling in important detail, her archive accomplishes one other feat: it returns to Zohra El Fassia her voice. Persistence and triumph are everywhere in those two boxes. She continued to put on her makeup and perform until the very end. Along the way, musicians, poets, and politicians paid her respect and homage. So too did her fans. In 1976, the year that Erez Bitton immortalized her in his poem “Zohra El Fassia’s Song,” Zohra El Fassia ascended a Mimouna stage in Jerusalem before hundreds, if not thousands. Thankfully, a French photographer captured the scene. Memory proved right. As is clear, her “soldiers” indeed fought “to clear a path through the crowd / to reach the hem of her skirt / to kiss the tips of her toes / to leave her a piece of silver as a sign of thanks.”

In 1994, in an interview with the Israeli newspaper Maariv two months prior to her death, Zohra El Fassia reflected on her life and legacy: “When I made aliyah to Israel they [the Jewish Agency] gave me a horrible apartment. I suffered from loneliness, no one visited me…Do you know why I cried? I wasn’t afraid of death, I knew one day I would die but I was afraid that after my death no one would remember who Zohra El Fassia was.” Luckily, memory and history have proved her wrong.

To learn more about El Fassia and other Jewish musicians from North Africa, visit Silver’s digital music archive, Gharamophone.

Citation MLA: Silver, Chris. “Sonic Geniza: Finding Zohra El Fassia in Los Angeles.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/sonic-geniza/.

Citation Chicago: Silver, Chris. “Sonic Geniza: Finding Zohra El Fassia in Los Angeles.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/sonic-geniza/.

About the Author:

Chris Silver is the Segal Family Assistant Professor in Jewish History and Culture, McGill University and the curator of Gharamophone.com… More

Citations and Additional References

1 Translation taken from Ammiel Alcalay, After Jews and Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 251.

2 While “the Big Game” usually involved UC Berkeley and Stanford, the latter had halted its football program between 1915-1919 citing the violence of the sport.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.