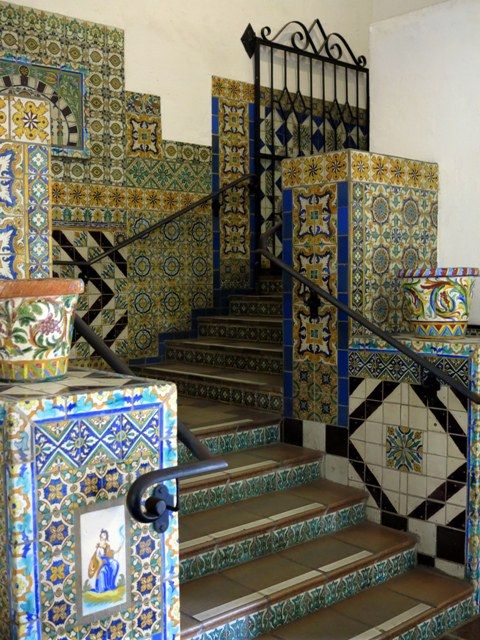

The “Spanish Revival” movement remade the landscape of Southern California by popularizing Andalusian and Spanish colonial architecture, ornamentation, and landscape design. Tiles were among its defining features, capturing southern Californians’ imagination and becoming inseparable from the Angeleno built environment. A single Jewish family from Tunis supplied many of these tiles, helping to craft a Californian aesthetic with deep global and Sephardic roots.

Like a good coffee table book, Un siècle de céramique d’art En Tunisie is filled with gorgeous images of Tunisian ceramics that decorate palaces, museums, and streets around the world. Perhaps surprising for this genre of writing, the book includes an extensive and intimate look at multiple generations of the Chemla family−Tunisian Jews whose ceramics business took their neo-Orientalist artwork from Iraq to California and beyond. Benefitting from an insider look made possible due to the authors’ personal connections to the story, Jacques Chemla, Monique Goffard, and Lucette Valensi reveal unexpected links between this family-owned business and landmark international architecture. including a historic theater in Harlem, numerous public and private buildings in Santa Barbara, department stores in Baghdad, and the Grand Mosque of Paris.

Like a good coffee table book, Un siècle de céramique d’art En Tunisie is filled with gorgeous images of Tunisian ceramics that decorate palaces, museums, and streets around the world. Perhaps surprising for this genre of writing, the book includes an extensive and intimate look at multiple generations of the Chemla family−Tunisian Jews whose ceramics business took their neo-Orientalist artwork from Iraq to California and beyond. Benefitting from an insider look made possible due to the authors’ personal connections to the story, Jacques Chemla, Monique Goffard, and Lucette Valensi reveal unexpected links between this family-owned business and landmark international architecture. including a historic theater in Harlem, numerous public and private buildings in Santa Barbara, department stores in Baghdad, and the Grand Mosque of Paris.

Jacob Chemla and Jewish life in Tunis, 1850-1950

The Chemla family first entered the artisanal world, and more specifically, ceramics, in the second half of the nineteenth century. Little is known about Haï Chemla, the family’s patriarch at the time, and the reasons behind his professional choices. His grandson, Mouche Chemla, recalls that Haï owned a workshop in the Potters’ Plaza, where pottery has been sold in Tunis’ old city since the eighteenth century, and he served simultaneously as a tax farmer.

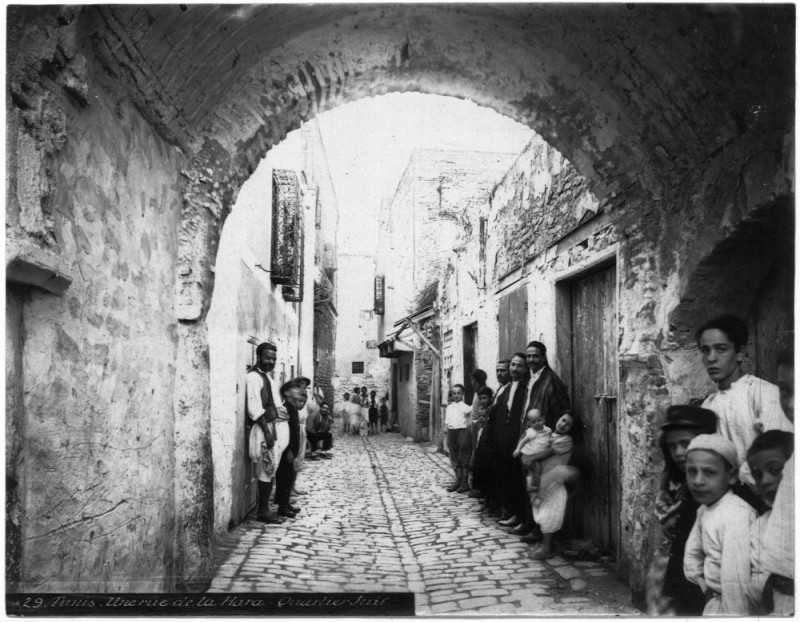

Figures regarding the size of Tunisia’s Jewish community, especially during the pre-colonial period, are not exact. Nevertheless, oft-cited estimates suggest approximately 24,000 Jews resided in Tunis at the beginning of the twentieth century, making it the largest concentration of Jews in the country, and approximately 20 percent of the city’s population.1 Despite having little information about the professional activities of Jews in Tunisia during this period, Un siècle does provide evidence that members of the Jewish communities in Tunis during the nineteenth century occupied many different occupations. Some were craftsmen and shop owners, while those with sufficient resources were at times able to hold intermediary, quasi-administrative positions in the Bey’s government. In particular, the authors point out that a new tax law implemented at this time, namely the leasing of taxes through financially able subjects of the Bey, allowed wealthier individuals, including some members of the Jewish community, to build inventories of ceramics as tax farmers could be paid in pottery (or other goods) rather than cash. As Mouche’s memories affirm, this seems to have been the case for Haï, although the fact that he left no inheritance for his six children or wife indicate that his work may never have been particularly lucrative.

It is clear that by the time Jacob Chemla, one of Haï’s six children, officially founded the family business in the early twentieth century, Jews of Tunis were enmeshed in even more sectors of the society. Paul Sebag, a French sociologist who wrote extensively about Tunisia and in particular, the Jewish communities therein, surveyed the types of professions that Tunisian Jews held in the early twentieth century and found the highest percentage were merchants and industrialists, or in the liberal professions.1 Jacob Chemla was the first Tunisian Jew to become a specialist in ceramic art, according to the authors of Un siècle. Similar to Sebag, they note that Jews were involved in many different sectors of the Tunisian economy at the beginning of the twentieth century, ranging all along the socioeconomic spectrum, from blacksmith to shop owner and merchant. However, they also emphasize that there was a division of labor between Jews and Muslims which included, ceramic art, traditionally a sphere for Muslim craftsmen.2

A pioneer even outside of ceramic art, Jacob was a Renaissance man of sorts who could read and write in at least four languages (Arabic, Hebrew, Italian, and French). Born around 1858, during his childhood, he likely received “traditional schooling within one of the modernized Jewish schools” established in Tunis during the mid-nineteenth century.2 Italian was likely used at Jacob’s school for subjects outside religious education (which were taught in Hebrew and Arabic), whereas his knowledge of French was probably acquired through informal means. This is reflective of yet another distinctive feature of Jewish life in Tunisia (and Tunis, more specifically): Tunisia was the receiving place for Jews from all over the Mediterranean basin and, over time, these different Jewish communities were stratified based on access to varying markers of social, cultural, and economic capital.

Keith Walters outlines in his work on education and the social histories of language use among Jews in Tunisia, drawing largely from figures collected by Sebag, two overarching categories to describe the diversity of community members–Twansa (which is the Tunisian Arabic word for Tunisian) and Grana (or Qrana, which is the Tunisian Arabic word for people from Livorno, Italy). The former, considered indigenous, included Jews of Amazigh (Berber) origins and those who immigrated after being expelled from Spain and Portugal during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The latter was composed of two different waves of Jews from various parts of the Mediterranean, including Italy, France, Gibraltar, and Malta, that resided in Livorno, Italy before immigrating.

As alluded to above, Jacob’s unusually diverse achievements reach far beyond his primary education. Above all, he was, as the authors of Un siècle deem, “a man of letters”–beginning an extensive career in journalism as a young man, not just writing, but also establishing several Judeo-Arabic publications, including two long-running journals Al-Bustān (The Garden), which published over 300 issues from its start in 1888, and Al-Haqīqa (The Truth), with over 30 issues of its own. Jacob was also a writer and translator in Judeo-Arabic, publishing two novels in the early 1900s and translating two texts into Hebrew (one related to the history of Jews in Spain during the Inquisition and the other, a famous French novel, The Count of Monte Cristo).

Jacob’s interests did not stop with literature, he also established a musical society, “El Allal,” and, perhaps more importantly, served as wakil–legal representative–at the rabbinical tribunal of Tunis in addition to his involvement in several philanthropic Jewish organizations. The authors of Un siècle interpret Jacob’s diverse engagements, particularly his extensive work in journalism and Judeo-Arabic writing more broadly, translating non-Jewish authors and texts, as signs of his “resolutely innovative spirit.” Furthermore, they note that Jacob’s membership to a modernist elite of the Jewish community in Tunis can be evidenced by material elements of his professional as well as personal style, such as, his owning a telephone and always wearing a traditional Tunisian hat, the chechia, in public.4

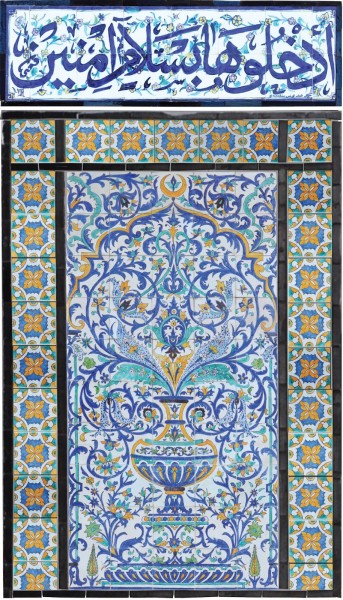

Certainly, Jacob’s standing within the upper echelons of Tunis’ social milieu helps explain how, by the early 1900s, little more than two decades after officially founding his business, he had already established working relationships with stateside (namely French colonial) and international architects. Subsequently, his ceramics were displayed in expositions around the world. Inspired by ancient decorative ceramics found in the Bardo museum and Zawiya Sidi Saheb in Qairawān (also known as the Mosque of the Berber), Chemla distinguished his work by revitalizing local styles, such as the use of cobalt blue, which had previously disappeared from Tunisian pottery.

Among Jacob Chemla’s collaborators were two principal architects for the French colonial Office of Public Works in Tunisia, Raphaël Guy and Jean-Émile Resplandy. Without a doubt, these partnerships were instrumental to Chemla’s business, which after World War I included his three sons–Victor, Albert, and Moïse (Mouche), becoming an official provider to the French colonial Office of Public Works. As a result, their ceramics were used in public projects throughout the country, including government buildings, villas, and the Pasteur Institute.

“Le Moment Américain” (“The American Moment”)

As Chemla, Goddard, and Valensi note, one defining marker of the Chemlas’ success was their diverse and extensive projects with various entities in the United States starting in the 1910s. Spanning several states, Chemla ceramics were a major feature not only in private home architecture–as was the case for several California mansions, including Casa de Herrero and Jackling House, later bought by Steve Jobs–but also, in decorating public buildings. For example, Chemla tiles lined the outer walls of the Renaissance Ballroom and Casino, also known as the “Renny,” a black-owned business, established by William H. Roach, that showcased monumental artists of the time such as Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington. Unfortunately, both the Jackling House and the Rennie have since been demolished, despite calls for preservation.

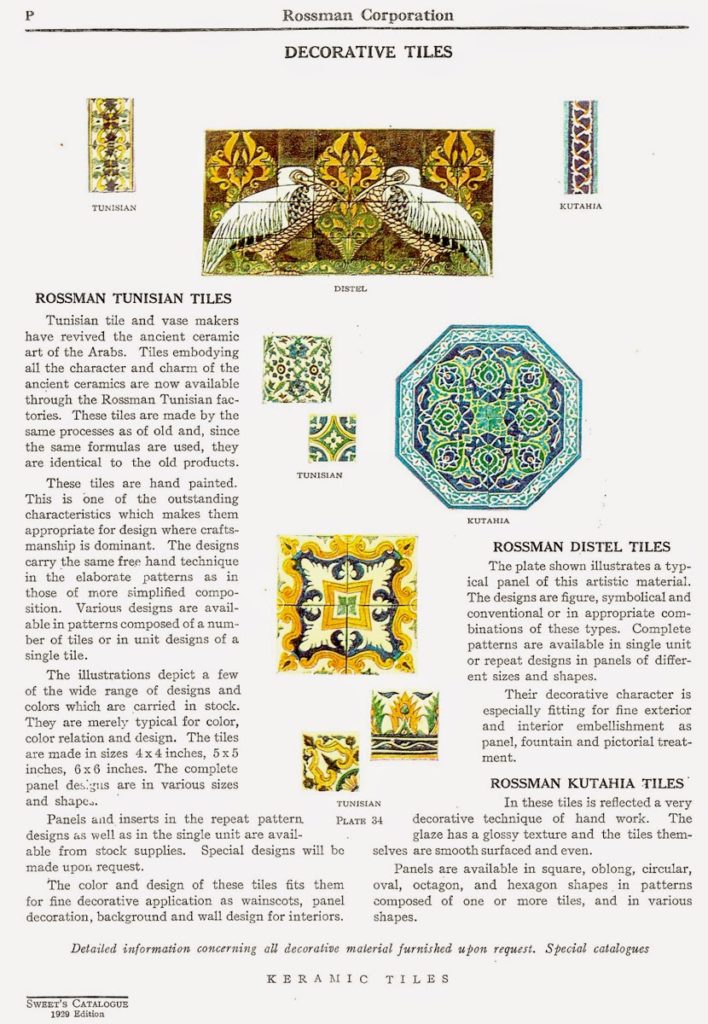

Little is known about how exactly the Chemla family was able to penetrate the American market, besides the fact that an American woman, known by her initials B. S. Hooker, imprinted on a pitcher that Mouche kept for years, provided the funding to import their tiles to the U.S. beginning in the 1910s. Additionally, agents in New York (the Rossman brothers) and San Francisco (E. L. Bradley) exhibited the Chemla work for sale.

A particular architectural movement that was flourishing in the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century inspired by rural Andalusian and Mexican (mainly Spanish colonial) architecture may have motivated Ms. Hooker to contract the Chemla family’s work. This trend emanated from, in part, the silent movie industry. Specifically, as Merry Ovnick describes in her work on the subject, motion picture settings, which drew on period-revival styles, popularized modernist aesthetics in the 1920s and 1930s. Major figures in this trend included Wallace Neff, who was known for using what he called “California style,” a mix of “stylistic inspirations drawn from northern Italy, southern Spain, and colonial Mexico.” For Ovnick, Neff was an example of how Southern California architects, whether or not they had set-design experience, would influence the popularity of this style, as they were often commissioned by movie stars and directors to create “movie-set-formed notions of how a mansion ought to look.” In turn, these designs were reproduced in illustrations for magazines or in the news, as was the case when Neff designed screenwriter Frances Marion and her husband, actor Fred Thomson’s home, further helping to popularize this trend.5

In fact, the authors of Un siècle mention Neff directly when discussing the Jackling House, a mansion designed by George Washington Smith outside Palo Alto in the 1920s for Daniel Jackling, a major leather industrialist at the time. After Steve Jobs acquired the house in 1984, unsatisfied with its design, he wanted it demolished to build a new structure but preservationists protested. Although they were ultimately unsuccessful, a condition of the demolition was that the decorative elements of the house would be removed beforehand. In turn, the house’s Chemla tiles, more than 4,000 units, were removed and eventually bought by “another rich proprietor” to decorate the walls of a similarly styled residence designed by none other than Wallace Neff.6

Considering the social and cultural cache of this booming trend, it is unsurprising that architects across the country were commissioning Chemla tiles for residences and businesses that mainly catered to the most privileged members of society. In Florida, Paul Chaplin, Kiehnel and Elliot, and Addison Mizner were responsible for private residences built in Miami and Palm Beach. In New York, Warren and Wetmore, Sterner and Wolfe, and Bertram Goodhue worked on both hotels and private residences, including the Commodore Hotel, the Hotel McAlpin (the largest hotel in the world for its time), and the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu. Interesting to note, Ovnick mentions that Goodhue contributed to the popularization of the Spanish colonial style through another venue outside the movie industry–state fairs–by modeling all the pavilions at San Diego’s Panama-California Exhibition of 1915 using Spanish colonial and Pre-Colombian Meso-American designs.7 In California, the main architects using Chemla tiles were Smith, already mentioned above, Reginald Johnson, and Mooser III. Aside from the Jackling House, Smith also designed Casa del Herrero, owned by another industrialist, George Steedman. Johnson worked on the Scripps campus in addition to various buildings throughout Santa Barbara. Together with Mooser III, they were also responsible for many parts of the CalTech campus.

When perusing images of Chemla projects in the U.S., it is daunting to consider the logistical challenges they faced shipping ceramic tiles from one end of the world to another long before speedy commercial transport existed. Casa de Herrero alone required over 20,000 ceramic tiles be imported from Tunisia to California in the 1920s. Work began at the Chemla factory in Tunis, where Italians and Tunisians, both Jewish and non-Jewish, handled every step of production, from crushing the clay to finishing artistic touches. After being carefully packaged, the tiles would take months to reach the buyer. In one telling example, the first shipment of over 7,000 tiles for the Casa de Herrero project took nine months to reach California.

Since the authors of Un siècle and other scholars of the region cited above noted that Jews in Tunisia held positions in many sectors of the local economy, it was probably not uncommon for Jews and non-Jews (namely, fellow indigenous Muslims) to work together in a single factory. However, Un siècle does not discuss whether or not groups were stratified to any extent within the factory’s hierarchy based on ethnic or religious backgrounds. At least one Muslim Tunisian worker, Mohamed Ben Ahmed El Zghonda, seems to have occupied a more powerful role in the company as he is described as a master worker, and pictured in a few photographs, side-by-side with Chemla family members. Furthermore, the authors of Un siècle argue that Mouche had a particularly close relationship with all the employees, as he was called Mushi or ‘arf Muris by the Tunisian workers and Monsieur Maurice by the Italians.8 Nevertheless, these nicknames likely reflect the workers’ hierarchical understanding of their relationship (however close) to Mouche since ‘arf and monsieur generally index deference for someone perceived as holding greater social, cultural, or economic capital in a given society.

It is also clear that the Chemla family employed at least one female designer, Gabrielle “Gabo” Pariente, who like El Zghonda, achieved enough renown in the company to have her own figural signature, which she used to mark her work. Joy Land has noted that in the early twentieth century female employment outside the home was rare for both Jewish and Muslim Tunisians, citing mostly correspondence from directors of Alliance Israélite Universelle schools in Tunisia and figures collected by none other than Paul Sebag.9 It is hard to extrapolate what the situation was for all indigenous women in Tunisia during this period, particularly when Land’s evidence is limited to testimonies of less than five AIU directors as well as a survey that covered only Tunis and may have received only a few hundred responses.

The authors of Un siècle suggest that Pariente’s employment was easier to facilitate due to her privileged status as daughter of a British national from Gibraltar, who was both a merchant in the grain trade and an honorary consul to Great Britain, in addition to her close relationship to the Chemla family, as one of her sisters married a Chemla son.10 Significantly, El Zghonda, one of the only Muslim Tunisians who appears to have risen in the ranks of the company’s hierarchy, never joined the Chemla family it what appears to various trips outside of Tunisia (including to France), whereas Pariente is pictured in Paris with the family. This may reflect the greater difficulty Muslim Tunisians experienced in obtaining necessary documentation, such as, French citizenship, which two of the Chemla brothers enjoyed, as well as, more broadly speaking, differences in the socioeconomic statuses of the Chemla and Pariente families compared to the broader pool of the factory’s employees, both Jewish and non-Jewish.

Going Home–Celebrating Independent Tunisia

With the Great Depression and a shift in global trends away from Spanish colonial style architecture, the Chemla business was forced to pivot away from the U.S. market and focus more regionally. Maintaining projects within Tunisia, Albert, Victor, and Mouche Chemla were contracted to decorate Dar El Kamila, situated in the exclusive La Marsa neighborhood of Tunis, future home of the French Ambassador to Tunisia, in addition to other villas, the main tennis club in Tunis, and the La Goulette train station.

When Mouche took over the business in the mid-twentieth century the Chemla style changed more dramatically, with more motifs inspired by Persian and Turkish art. For example, after being commissioned to decorate the palace of Habib Bourguiba, the first president of the independent Tunisian Republic, Mouche created large ceramic panes depicting scenes from the story of Khosrow and Shirin, a Persian romance written by the medieval author, Nezami Gandjevi. Here, it is important to consider the impact the Chemla family’s contribution to Bourguiba’s palace may have had on public perceptions of Tunisian Jewish support for independence. Scholars have noted that unlike the situation in other North African countries, like Morocco, explicit and public support for the Tunisian nationalist movement among indigenous Tunisian Jews appears to have been limited, if not non-existent. Furthermore, some Jews (as well as Muslims) were naturalized as French citizens, including Albert and Mouche Chemla, which may have further complicated perceptions of Tunisian Jewish support for independence.11 Nonetheless, the writers of Un siècle are quick to note that Jacob Chemla never obtained French nationality and maintained his Tunisian passport all his life, despite his sons’ naturalization. We are only left to wonder whether the Chemla participation in decorating this monumental symbol to Tunisian independence was (and continues to be viewed) as a testament to interfaith solidarity for a Tunisia free of French colonial rule.

Having established his reputation in France, named Best Worker in 1955, an award given for excellence in craftsmanship, Mouche eventually left Tunisia to settle in La Garde–Freinet. There he obtained a chapel from the municipality that he later converted into a space for teaching “La Poterie des Maures” (“Moorish pottery”). France, unsurprisingly, has become a space for the maintenance of Tunisian Jewish and Muslim heritage. Philippe Barbé notes, citing the work of Patrick Simon and Claude Tapia, that le quartier tune (meaning Tunisian neighborhood in French slang), also called Belleville, in Paris has served as a site for recreation of a shared Muslim and Jewish Tunisian past, promulgated not only by older generations that may have lived in or visited the hara (Jewish quarter) of Tunis but also their children.12 Likewise, since the 1990s in Tunis, through the leadership of artists as well as independent aficionados like Mohamed Messaoudi, who established the Driba-AD93 workshop, Chemla pieces have been restored and protected for future generations to see.

Today, Chemla family ceramics can be viewed throughout the globe–from Santa Barbara’s City Hall to the Ethnographic Museum in Geneva. Perhaps most fittingly, their artwork continues to decorate the streets, buildings, and villas of Tunis so that any wanderer can catch a glimpse into this lesser-known moment of Tunisian history when local art met international commerce.

Citation MLA: Stoolman, Jessie. “Southern California ‘Spanish Revival’ by way of Tunis.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/spanish-revival-by-way-of-tunis/.

Citation Chicago: Stoolman, Jessie. “Southern California ‘Spanish Revival’ by way of Tunis.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/spanish-revival-by-way-of-tunis/.

About the Author:

Jessie Stoolman is a graduate student in Anthropology at UCLA … More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Haim Saadoun, “Tunisia” in Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, ed. Norman A. Stillman (Leiden: Brill, 2010, online ed., 2010).

2 Jacques Chemla, Monique Goffard, and Lucette Valensi, Un siècle de céramique d’art en Tunisie: Les fils de J. Chemla (Paris: Édition Déméter/Éditions de l’Éclat, 2015), 14.

3 Keith Walters, “Education for Jewish Girls in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Tunis and the Spread of French in Tunisia,” in Jewish Culture and Society in North Africa, ed. Emily Benichou Gottreich and Daniel J. Schroeter (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 257-281, see esp. 259-263.

4 Chemla et al, Un siècle de céramique d’art en Tunisie, 16.

5 Merry Ovnick, “The Mark of Zorro: Silent Film’s Impact on 1920s Architecture in Los Angeles,” California History 86, no. 1 (2008): 28-64, see esp. 28, 47.

6 Chemla, et al, Un siècle de céramique d’art en Tunisie, 51.

7 Ovnick, “The Mark of Zorro,” 61.

8 Chemla et al, Un siècle de céramique d’art en Tunisie, 39.

9 Joy A. Land, “Corresponding Women: Female Educators of the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Tunisia, 1882-1914,” in Jewish Culture and Society in North Africa, ed. Emily Benichou Gottreich and Daniel J. Schroeter (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 239-56, see esp. 244-247.

10 Chemla et al, Un siècle de céramique d’art en Tunisie, 41.

11 Fayçal Cherif, “Jewish-Muslim Relations in Tunisia during World War II: Propaganda, Stereotypes,and Attitudes, 1939–43,” in Jewish Culture and Society in North Africa, ed. Emily Benichou Gottreich and Daniel J. Schroeter (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 305-20, see esp. 314-315.

12 Philippe Barbé, “Jewish-Muslim Syncretism and Intercommunity Cohabitation in the Writings of Albert Memmi: The Partage of Tunis,” in Jewish Culture and Society in North Africa, ed. Emily Benichou Gottreich and Daniel J. Schroeter (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 107-27, see esp. 122-123.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.