Blending sacred traditions, folkways, and secular cultural influences, weddings (and the customs and rituals surrounding weddings) have, for centuries, played a central role in the transmission and maintenance of Iranian Jewish culture. Marriage consecrated bonds between and within families as well as Iranian Jewish communities, and both shaped and was shaped by the dynamics of sexuality, femininity, and gender roles of the surrounding society. As such, marriage practices provide a vital frame for understanding how government policies, world events, and migration have shaped Iranian Jewish women’s identities over time. Drawing on interviews conducted with Iranian Jewish women living in Los Angeles for my book, From the Shahs to Los Angeles, in this essay, I explore the experiences of three generations of Iranian Jewish brides – women who lived under Iran’s constitutional monarchy from 1925 to 1941; women who lived under the westernization and modernization project of Muhammed Reza Shah from 1941 to the Islamic Revolution of 1979; and women who were born in Iran or America and came of age in Los Angeles, from the 1970s to today – as a means of understanding the evolution of Iranian Jewish womanhood in the twentieth century.

Jewish Women and the Qatar Dynasty (1789-1925)

The Constitutionalist Revolution of 1906 is often cited as the beginning of the Iranian people’s struggle for freedom as it established, for the first time, a constitution that afforded Persian subjects rights and created a representative parliament, with each religious minority, except the Baha’is, given the right to elect delegates to represent their communities. For Persian Jews, as Habib Levi described, the Revolution functioned as a sort of “Jewish Emancipation,” removing many of the restrictions on Jewish mobility imposed by the Shi’a Qajar Dynasty (1789-1925). Jews were no longer barred from renting or owning property beyond the walls of the mahaleh (Jewish quarter), many of the restrictions on their economic participation and access to education were lifted, and they were granted the right to publish their own Jewish newspaper, Shalom. Jews were also no longer considered to be “unclean,” a status that had been used to justify forceful conversions throughout history in addition to daily acts of humiliations and mistreatment.1 Although they continued to occupy a minority status in Iran, 1906 marked an important step for Persian Jews towards the civil equality that Jews had achieved in other parts of the world in the nineteenth century.

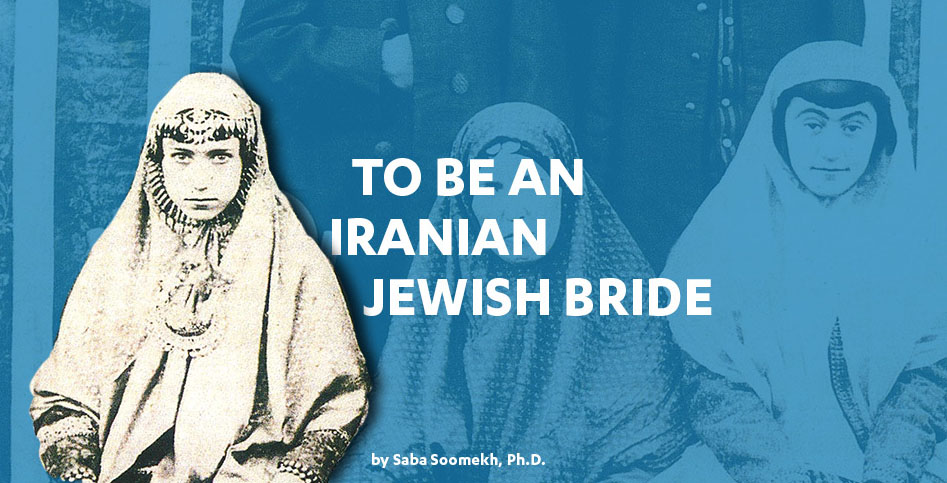

For Persian Jewish women, however, these new freedoms remained largely inaccessible. Jewish women were still required to wear a chador-a head scarf worn by Shi’a Muslim women–and largely confined to the home where they were expected to perform all child-rearing and housekeeping tasks. Marriages were arranged entirely by their families who chose spouses based on their economic status and social standing in the community. Girls were expected to marry at a young age, and in some areas–such as Mashhad, where Jews had been forced to convert to Islam in 1839–engagements were arranged for newborn babies in order to prevent them from marrying Muslims later in life.2 After they were married, these young brides left her parents’ homes and moved into their husband’s household, most often joining their spouses’ brothers and their wives as well as their in-laws. In this matriarchal hierarchy, the mother-in-law was at the top and the daughters-in-law at the bottom, with those who gave birth to boys having the ability to move up. When I asked the women I interviewed what it was like for them to marry at such a young age in an arranged marriage, most responded that their lives were dependent on luck: not only if they were lucky enough to have an arranged marriage to a man that was good to them, but also if they were lucky enough to have a mother-in-law that was good to them.

My great-grandmother, Naneh Jan, pictured here on her wedding day in Hamadan, Iran in 1910, was just ten years old when she was married, her experience was similar to many of the women that I spoke to in my interviews. The photograph captures the mix of traditions that influenced Persian Jewish wedding customs in the early 20th century. These customs were not limited to the wedding ceremony itself; a series of rituals were part of the wedding celebration, each designed to ensure fertility, economic success, and, most importantly, to ward off the evil eye.3 The fear of falling victim to a curse, or “cheshm khordan” (lit. translated to being struck by the eye), has been embedded in Iranian culture since the time of the Zoroastrians, and is deeply rooted Persian Jewish tradition as well. The superstition took on ever more significance in a time when child brides were having numerous children and the chances of the young mother and her babies surviving childbirth were tenuous. The wedding jewelry, placed on young brides like my great-grandmother, functioned both as a decoration and as a talisman, worn both to ward off the evil eye and to ensure fertility and safety for her and her future children.

The henna that adorns my great-grandmother’s hands was also applied to ward off the evil eye as part of a wedding custom. In this ritual, known as henna-bandon, women gather in the home of the bride’s family to put henna on the bride’s hair and on the hands of all the women in attendance and to light esphan, the seeds of wild rue, in order to keep the evil eye away from home and loved ones. The esphan is placed over the fire, usually on a stove, and once it starts popping, the fire is turned down and the bride inhales the scent of the herb. At that point, the matriarch of the house says a prayer asking God to repel the evil eye from that specific person or the family. She then stretches her hand out over the recipient’s head, circling her hand over the head three times, and finally, she taps the recipient on the shoulder three times.4 Even today, a majority of Iranian Jewish women, from the most religious to the most secular, continue to do this ritual, not just in advance of their weddings but sometimes on a weekly basis. The women I interviewed explained that lighting esphan is an important part of their duties as matriarchs to be the guardian of the house and protecting their families from the jealousy and negativity of others.

The photo reveals that at a time when women were excluded from the Jewish public sphere, when they were not attending synagogue services and were illiterate in Hebrew, it was within the home that women, especially the matriarch, exercised power and responsibilities. A woman’s life was dictated by her parents, her husband, and her mother-in-law. She, in turn, was responsible for the protection and well-being of her family against the evil eye. The most important ritual a woman performed at that time was to be married, and by doing so, to become the guardian of the home.

Jewish women and the Pahlavi Dynasty (1925 – 1979)

After years of turmoil, internal conflict, and a coup d’état, Reza Shah Pahlavi took control of the throne in Iran in 1925. Central to his reforms was the separation of religion and politics: Reza Shah orchestrated the expulsion of even the most senior clerics from government administration and did not permit them to meddle in state affairs. The secularization of the state enabled many Jews to prosper financially, and in turn to establish new Jewish institutions, such as Kurosh Elementary School and High School in Tehran. However, in the later years of his reign, Reza Shah lost significant support as he extended a hand of friendship to Hitler and brutally suppressed his domestic enemies. When the British and Soviet armies invaded, the Iranian army collapsed and Reza Shah was forced to abdicate his throne and retreat into exile.

The coronation of his son, Mohammad Reza Shah, in 1941, brought about a resurgence of the Jewish people of Iran. In conjunction with Western allies, including the United States, Reza Shah made significant efforts to transform “backward” Iranian society into the image of the modern West and replace traditional sources of identity, such as ethnicity and religion, with secularism and modern institutions.5 These modernization programs included a reorganization of the civil service, industrialization, urbanization, the nuclearization of the family, education, and paid employment, all of which opened up substantial new possibilities for Persian Jews. Under Reza Shah’s rule, Jews were prominent figures in economics, industry, commerce, higher education, administration, and the arts and sciences. Educational opportunities for Iranian Jews increased, as Jewish schools, summer camps, and seminars for training teachers were opened and hundreds of Jewish students went to Europe and America to pursue advanced studies.6 Education created upward economic mobility, as did the financial boom generated by Iran’s expanding oil industry and by the 1960s, the Iranian Jewish community had been transformed from a poor, isolated community into an affluent and well-integrated one, with a significant upper class.7 The Shah also recognized Israel and repeatedly affirmed Israel’s right to exist, publicly declaring that Iran and Israel should maintain economic ties; and as a result of the implementation of various treaties, Israeli organizations engaged in a wide range of activities in Iran. For these reasons, Habib Levy has argued that “the years of Mohammad Reza Shah’s reign may be considered the zenith of Jewish Iranian well-being and prosperity.”8

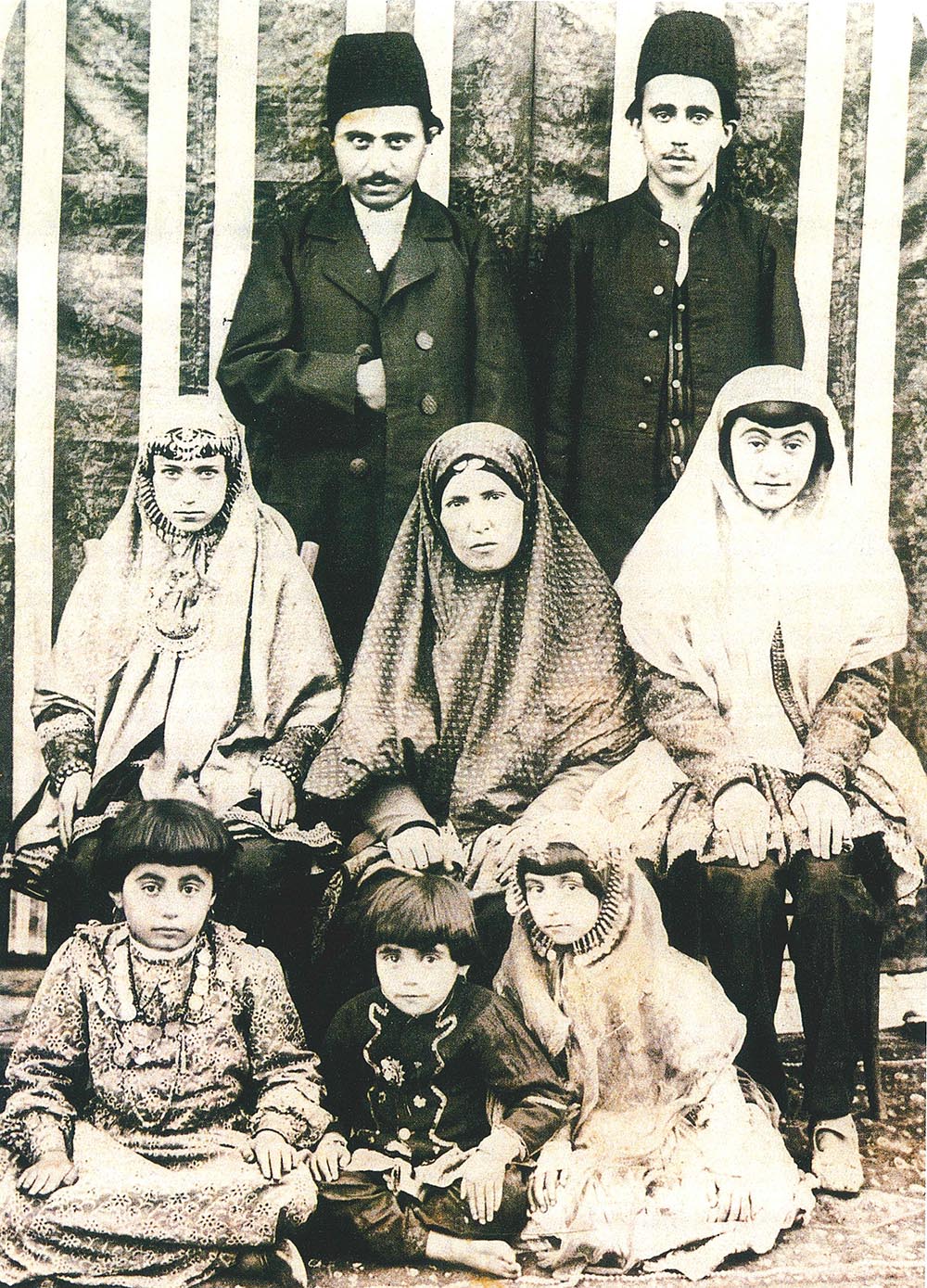

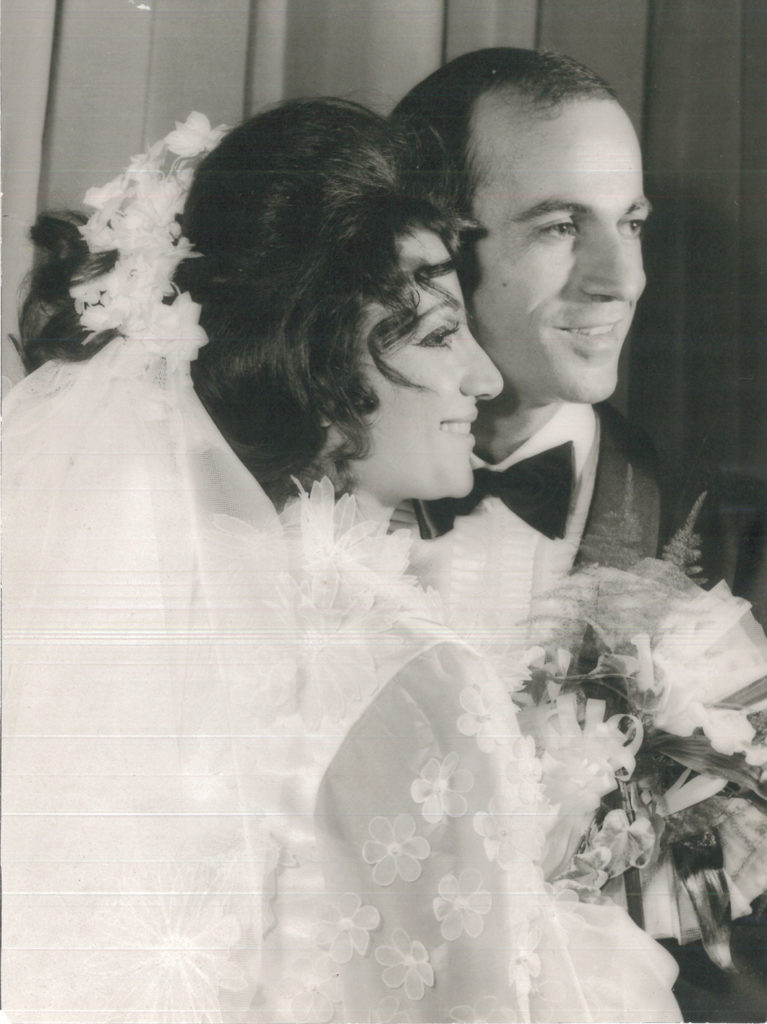

Among the most significant cultural changes that unfolded during the Pahlavi dynasty related to the status of women. Jewish girls, who until a few generations earlier had received no education at all, were now on equal footing with boys and studied at all levels. Most of the Persian Jewish women I interviewed received secular or private school educations (those with financial means would send their children abroad to schools in Europe), many attended Tehran university and had careers after college (although it was popular for many women to quit their jobs once they were married). But across the spectrum, educational and employment opportunities increased for Iranian women, and by 1976, the rate of literacy among women was 35.7 percent, and 11.3 percent of urban women entered the workforce.9 Personal style also became a new avenue for personal expression: Reza Shah banned the chador in 1936, and after his son came into power in 1941, Iranian women increasingly appropriated western style clothing, hairstyles, and make up. A majority of Iranian Jewish women were choosing their own marriage partners, getting married at an older age (in their late teens and early twenties), and not moving in with their in-laws (although the mother-in-law remained an intimidating figure). Those with financial means had elaborate weddings, wore westernized bridal dresses, and honeymooned in Europe. And, in 1963, Reza Shah Pahlavi gave women the right to vote. A new, “modern” type of Iranian Jewish emerged – captured in this photo of my mother taken in 1970s Tehran.

My parents were married in Tehran in 1970. Before her wedding, my mother attended the hammam, public bath, where her eyebrows were threaded and shaped for the first time. Traditionally, a woman did not shape her eyebrows, or for some, remove facial or body hair, until right before her wedding. It was at the hammam that the women in the bride and groom’s family gathered to thread the bride, tell stories, and have the henna-bandon ceremony. Unlike the generations before her, my mother did not have an arranged marriage and my parents moved into their own apartment after their wedding. Women from this generation had more autonomy than what was allotted to the women before them. While there was still a lot of respect and reverence given to their mother-in-law, it was more common for newlyweds, who had the financial means, to move into their own home and thus, many women did not have to deal with the matriarchal hierarchies that the generation before them experienced.

Even as women appropriated the secularism of the Shah’s regime in public, their duties to the health and well-being of their families endured in the home. Iranian Jewish women valued and cherished their Judaism and practiced it to some degree in their homes, but in their public life at work or at school, they mostly wanted to be seen as just Iranians—not Jewish Iranians. Thus, their religiosity consisted of lighting the Shabbat candles on Friday night and having a traditional Shabbat meal. Many interviewees said they would go out after they had Shabbat dinner with their families, meeting girlfriends at coffee shops, or even going out to dance. Very few of the women I interviewed attended synagogue on Saturday mornings because they had to attend their high school or college classes (Friday was the only day that Iranians had off).

Thus, for the women living under the secular regime of the Shah, religiosity consisted of maintaining a kosher home, celebrating the Sabbath together, and attending synagogue mainly during Jewish holidays. All of the women agreed that the most important aspect of maintaining their Judaism was socializing with and marrying Jews, yet they were still able to successfully integrate into secular Iranian society. Thus, they took advantage of the economic mobility the Shah allowed the Jews to achieve while simultaneously maintaining an insular Jewish community.10

Migration and Reinvention in Los Angeles

In the fall of 1977, a revolutionary upheaval began with the outbreak of open opposition movements, and Jews in Iran once again found themselves threatened by their Muslim neighbors. Iranian Jews realized that their previous assets had turned into liabilities: their prominent socio-economic status, their identification with the Shah and his policies, and their attachment to Israel, Zionism, and America were all held against them by Khomeini and his followers.11 It is estimated that by 1978, some 70,000 Iranian Jews had fled Iran, many of whom immigrated to the United States. This immigration to the United States is important in a religious sense because, for the first time, Iranian Jews find themselves in a secular society where they faced the challenges of retaining their Judeo-Persian identity. It has also had a significant impact in Los Angeles, where over the course of forty years, the Persian Jewish community has grown to include multiple generations comprising some 80,000 people.

Iranian Jewish weddings in Los Angeles are large affairs where one must include extended family members in social gatherings, thus paying respect to both the bride and groom’s family but also, to their sibling’s in-laws, family friends, and basically, anyone who has ever invited the bride, groom, and their parents to their wedding. There are many parties that take place before the actual ceremony. It has become common for women, no matter what their religious background, to attend the mikveh (ritual bath) before the wedding. There is an engagement party, a shirini-khorān (a party celebrating the bride’s family brining sweets to the groom’s family as a gesture of accepting the groom’s proposal for marriage), henna-bandon, a ketubah-signing party, and many times, all these traditions and rituals (except for the mikveh) can take place at the engagement party. Many Conservative and Reform Iranian weddings will have a female rabbi or cantor officiate the wedding, something that was never done in Iran. Demonstrating that while many weddings still appropriate traditional Iranian rituals, the Reform and Conservative tradition of having an egalitarian clergy is something that has been appropriated from the Ashkenazi community into Iranian weddings.

Persian Jewish women of my generation–most of whom have only known life in America and whose knowledge of Iran is based on the romanticized stories of their parents and elder family members–have to balance multiple identities as Americans, Iranians, Jews and women. They do not live in the same physical space or the same sociocultural landscape of their parents’ youth and do not have their parents’ nostalgic allegiance to the old country. Like many children of immigrants, their identities and interests are shaped by American cultural norms and yet, Iranian Jewish culture continues to be a major aspect of their lives. Many of the women I interviewed spoke about the pressures they feel to embrace American culture while feeling held back by traditional Iranian Jewish expectations. The women feel physical pressure to look their best, material pressure to dress their best, academic pressure to get good grades and attend the best universities, and one of the most difficult pressures placed on young Iranian Jewish women is the belief that they must live their lives for their family and community. The American concept of having boundaries with your parents and extended family does not exist–the idea is “we live for you and you live for me.”12 A majority of Iranian Jewish young women are not raised to be independent; it is not a trait that is encouraged in the community. Many women do not have the option to go away to college or live outside of their parents’ home until they get married. Recently, it is becoming more popular for young women to spend a semester abroad or spend their summers traveling to Israel or Europe, but that is sanctioned amongst the more liberal Iranian Jewish families.

While first-generation Iranian Jewish women can feel torn between their hybrid identities, we are seeing more women break out of traditional roles expected of them and they are navigating both worlds and breaking the cultural glass ceiling. Instead of marrying doctors and lawyers, they are becoming doctors, lawyers, dentist, realtors, and physicists. Many first-generation women are also embracing careers that are less traditional such as entrepreneurs, scholars, social activist, rabbis, cantors, and careers within the arts. And while in the past it was expected for women to work only until they were married, these women are continuing their careers while married and raising families. These first-generation Iranian American women are in the process of a cultural syncretism and mixing that produces a hybrid identity that allows them to live in plural worlds revolving around their Iranian Jewish culture, their American landscape, and their gender. They are appropriating a more egalitarian lifestyle, while still respecting and paying homage to their parents, community, and culture.

Citation MLA: Soomekh, Saba. “To Be an Iranian Jewish Bride.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/iranian-jewish-bride/.

Citation Chicago: Soomekh, Saba. “To Be an Iranian Jewish Bride.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/iranian-jewish-bride/.

About the Author:

Saba Soomekh is the Assistant Director of Interreligious and Intergroup Relations for the Los Angeles American Jewish Committee… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 Habib Levy, Comprehensive History of The Jews of Iran: The Outset of the Diaspora ed. Hooshang Ebrami, trans. George W. Maschke (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1999), 493.

2 Esther Shkalim, “Wedding Customs,” in Light and Shadows: The Story of Iranian Jews, ed. David Yeroushalmi (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2012), 124.

3 Ibid.

4 Saba Soomekh, From the Shahs to Los Angeles: Three Generations of Iranian Jewish Women Between Religion and Culture (New York: SUNY Press, 2012), 40-41.

5 Parvin Paidar, Women and the Political Process in Twentieth-Century Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 8.

6 Michael Reichel, Persian American Jewry at a Crossroads: Will the Traditions Continue? (New York: LV Press, 2004), 64.

7 D. Mladinov, “Iranian Jewish Organization: The Integration of an Émigré Group into the American Jewish Community,” Journal of Jewish Communal Service (Spring 1981): 245-248.

8 Levy, Comprehensive History of the Jews of Iran, 554.

9 Ibid., 544-547.

10 Soomekh, From the Shahs to Los Angeles, 50-58.

11 David Menashri, “The Pahlavi Monarchy and the Islamic Revolution” Esther’s Children: A Portrait of Iranian Jews, ed. Houman Sarshar (Beverly Hills: Center for Iranian Jewish Oral History, 2002), 395.

12 Soomekh, From the Shahs to Los Angeles, 114-115.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.